Peruvian Filmmaker Rossana Díaz Costa on her Passion for Cinema and an Hispanic Classic

By Catherine Jewell, Information and Digital Outreach Division, WIPO

Rossana Díaz Costa grew up with a passion for literature and film. She studied literature, but as a self-confessed “movie maniac,” soon decided to focus her attention on filmmaking. “I love my life in literature, but it’s something I do alone, whereas filmmaking, when you have the money, is amazing. Shooting a film is like magic, you see your script come to life,” Díaz Costa explains.

Shooting a film is like magic, you see your script come to life.

Having completed her PhD in literature in Spain, Díaz Costa pursued her filmmaking ambitions, studying directing and screenwriting at film schools in La Coruña and Madrid. But on returning to Peru, carving out a filmmaking career was a challenge. Díaz Costa explains: “It was very difficult to be a filmmaker in Peru, where there's no cinema industry, and being a woman makes it twice as difficult. It’s very complicated. But when there's a little monster in your head that tells you to make a film, you do it.”

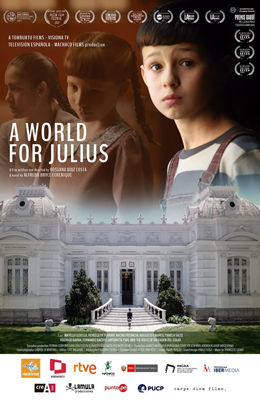

to make a film adaptation of her favorite novel,

A World for Julius (Un Mundo para Julius) by

the renowned Peruvian novelist Alfredo Bryce

Echenique. (Photo: Courtesy of Rossana Díaz Costa)

In 2022, Díaz Costa fulfilled a long-held ambition to make a film adaptation of her favorite novel, A World for Julius (Un Mundo para Julius) by the renowned Peruvian novelist Alfredo Bryce Echenique. The film premiered in 2021 to much acclaim and was nominated for a 2022 Gaudi Award. Díaz Costa recently spoke with WIPO Magazine about her filmmaking journey, the challenges she faced as a female director and how she is promoting filmmaking in Peru, especially among girls and women.

What was it about A World for Julius that captured your imagination?

I first read the novel when I was 12 years old. It was the first novel I read from the adult world, although the story is about Julius’ experiences as a child. It made a big impression on me, changed my outlook completely, and raised many questions about things I didn’t really understand about my country at the time. It explored issues of inequality, racism and gender violence through the eyes of a child. As a child myself, I could relate to the story, even when I didn’t fully understand these issues. So, I read the novel every year through high school. At university, I used it as a reference in my general studies class, and at film school in Madrid, I used it in my film adaptation class. My teacher thought I was crazy to use a 600-page novel for that exercise – but I just had to. It’s difficult to explain, but the novel has followed me.

The idea of making A World for Julius into a film was always at the back of my mind. But that was a huge responsibility, because it’s a very important novel from Peru and the Hispanic world. I met the author, Alfredo Bryce Echenique, when in Spain. That was a very important moment for me.

At what stage did you decide to make it into a film?

After I made my first film, I taught at university in Peru for many years, and every time I mentioned the novel A World for Julius to my students, they didn’t know what I was talking about. I couldn’t believe they hadn’t learned about this classic in school. At the same time, I saw that Peru hadn’t changed at all and seemed to be repeating the root problems outlined in the novel. So, I decided the time was ripe to make it into a film. That way, I could introduce it to new generations and shine a light on its social discourse, which remains relevant.

Making the film brought together my two professional loves – literature and film – it was a perfect marriage. I started writing the script without knowing if I would ever get the rights to make the film. It was a crazy thing to do. Usually, you get the rights first and then write the script.

Making the film brought together my two professional loves – literature and film – it was a perfect marriage.

Then I wrote to Bryce Echenique’s literary agent in Spain to ask if I could get the rights to the novel. They told me that he was old and sick and that on five previous occasions producers had obtained the rights but had not made the film. So, they were only going to give the rights to people who had written a first draft of the script. They thought they were going to just brush me off with that and were shocked when I told them I had already written it! I sent it to them within a week!

What happened next?

The agent offered me a Hollywood price for the rights, which was beyond my reach, so I wrote to Bryce Echenique explaining the situation. Luckily, he had seen my first film and liked it, so he instructed his agent to offer me a 50 percent discount on the rights. That made the project feasible. Since then, Bryce Echenique and I have become great friends. He’s a great moral support.

How did you go about adapting a 600-page book into a film?

I had to decide what I really wanted to show in the film. The novel is wide-ranging, but it’s essentially a coming-of-age story about how the child Julius slowly loses his innocence when he witnesses the injustices that take place in his own home. Julius learns that Peruvian society is divided into “the haves” and the have nots” —and he’s not happy about it. In fact, he’s a victim of the same wealthy class to which he belongs. But that still left me with a 300-page novel. So, I had to select the most compelling episodes in Julius’ life that worked from a cinematographic viewpoint. I had a lot of fun doing that.

What did it cost to produce the film and how long did it take to make it?

It cost around USD 800,000 to make. That’s nothing. It’s set in the 1950s, so art direction – the sets, costumes and props that correspond to that era - was the most expensive and time-consuming part of the production. The shooting itself was very short, just 25 days. But it took two years to get to those 25 days. I would have liked more time, but we didn’t have the money.

What made the film a success?

It deals with timeless, universal topics. We’ve all been children and can relate to that and issues of inequality, racism and gender violence are still all too common. The world’s social conflicts stem from the huge gap between people who have money and those who don’t. Audiences who see the film draw parallels with their own country and extend the topics to their own reality. At the end of the film, I also added my own twist - it doesn’t appear in the novel - because I wanted people to understand that these issues are still shaping people’s lives to this day.

What does cinema mean to you?

For me, cinema is more than a passion, it's a way of transmitting ideas. I also write literature, but with cinema you can reach more people. Many people don't read, but they like going to the movies. It’s a way of making people think about why things are the way they are and how we can change them. If even one person decides to change things for the better, that's enough. People need to talk about these things.

For me, cinema is more than a passion, it's a way of transmitting ideas.

How would you like to see the cinema evolve in Peru?

I would like Peru to have a public film school. That’s how we can start developing the specialist skills needed to build a film industry in Peru. While there is some government support for film makers, we really need our policymakers to recognize that it is in Peru’s interests to have a film industry and to make our creative sector a priority.

Why did you set up your own production company?

I had to become a film producer – I really don’t like that side of the business – because I needed to secure funding to make the film and the only way to do that was to set up my own production company. In Peru, you cannot find anyone in the private sector to fund films. They generally don’t see any money in them. Thankfully, I found various associate producers—individual people, not companies—who decided to invest in the film.

What was your experience of film distribution?

Film distribution was new to me. The film premiered in November 2021, about a month after they reopened following COVID. It ran for seven weeks, which was a nice surprise. It also did very well at film festivals and attracted interest from various universities offering courses in Latin American studies, literature, and communications. I hadn’t foreseen that revenue stream. But unfortunately, the film never made it to Netflix and Amazon because of a terrible mistake. Without my knowledge, one of the partners, a TV channel, had placed the film on their own platform and that ruined its exclusivity. That was a tough lesson to learn. I still have a lot to learn about film distribution.

What has been your experience as a female filmmaker?

It has not been easy. Peru has a very macho culture, and it has taken some time for people to recognize that a woman can make a film. The gender bias among funders and film critics is so frustrating. For example, when I approached a bank to fund A World of Julius, they couldn’t believe I didn’t have a male producer. Interestingly, when I was accompanied by my Argentinian producer, a man, for my first film, the doors suddenly opened. I can tell a thousand similar stories. But on set, I have never had a problem. The men in the crew have always been very respectful.

Women only represent 15 percent of all filmmakers in Peru […] But I am very optimistic about the future because more and more women are interested in making films, scriptwriting and learning about directing and producing films.

I am President of an Association called Nuna - it means “soul” in Quechua - which brings together around 45 Peruvian women film directors. We’ve all shared similar experiences and support each other. Through the Association, we organize mini film festivals featuring the work of female directors. They’re very popular. We also go into schools to show pupils that women can and do make films.

How do you see the future for women directors in Peru?

Around 20 Peruvian women in Nuna have made long feature films, including documentaries. Another 30 make short films. Women only represent 15 percent of all filmmakers in Peru and only one percent of them are not from Lima. But I am very optimistic about the future because more and more women are interested in making films, scriptwriting and learning about directing and producing films. They’re also showing interest in the technical side of cinematography, which has always been male dominated. In the next 20 years, I think we’ll see many more women filmmakers in Peru.

What advice do you have for aspiring young filmmakers?

First, as a filmmaker, you need to understand intellectual property and the rights you have. That will enable you to protect your work, earn income from it and fight against film piracy. It’s very important that you don’t waste all the effort you put into your work by allowing pirated versions on DVD or YouTube. Many people think piracy is normal, but it shows a total lack of respect for your work.

Everyone wins if we achieve a balance between the public’s right to art and the creator’s right to be recognized and rewarded for their work.

Some people think that letting everyone see their work for free is good for the public, but if filmmakers can’t earn a living from their work, how can they afford to create new films? Everyone wins if we achieve a balance between the public’s right to art and the creator’s right to be recognized and rewarded for their work. There’s still a lot of education to do around this.

Second, for girls interested in filmmaking, my message is: don’t be afraid. Don’t let one bad experience hold you back. Get in touch with other women who are making films and create your own support group.

The WIPO Magazine is intended to help broaden public understanding of intellectual property and of WIPO’s work, and is not an official document of WIPO. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WIPO concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication is not intended to reflect the views of the Member States or the WIPO Secretariat. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WIPO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.