3D printing, the Maker Movement, IP litigation and legal reform

By Matthew Rimmer*, Professor in Intellectual Property and Innovation Law at the Faculty of Law in the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Brisbane, Australia

3D printing is a field of technology that relies upon additive manufacturing (as opposed to traditional subtractive manufacturing). 3D printing has also been associated with the Maker Movement – a social movement focused upon developing and sharing design files.

The field of 3D printing is currently undergoing a transitional phase. The consumer 3D printing revolution – which was aimed at one day seeing a 3D printer in every home – has been a disappointment. The pioneering home 3D printing company MakerBot was embroiled in a number of controversies over its changing approach to intellectual property (IP), resulting in disenchantment with the open source maker community and alienation from its user-base. Bre Pettis, the former head of MakerBot, reflected in an interview, “the open-source community cast us out of heaven.” In the end, MakerBot was taken over by the leading 3D printing company Stratasys and was restructured and repurposed.

A number of other key companies became insolvent. TechShop, a chain of membership-based, open-access, do-it-yourself workshop and fabrication studios, went into bankruptcy. Maker Media – which runs Make Magazine and a couple of maker festivals in the United States – went into administration. Dale Dougherty, founder of Make Magazine has sought to revive the venture with Make Community LLC.

Industrial 3D printing continues to advance

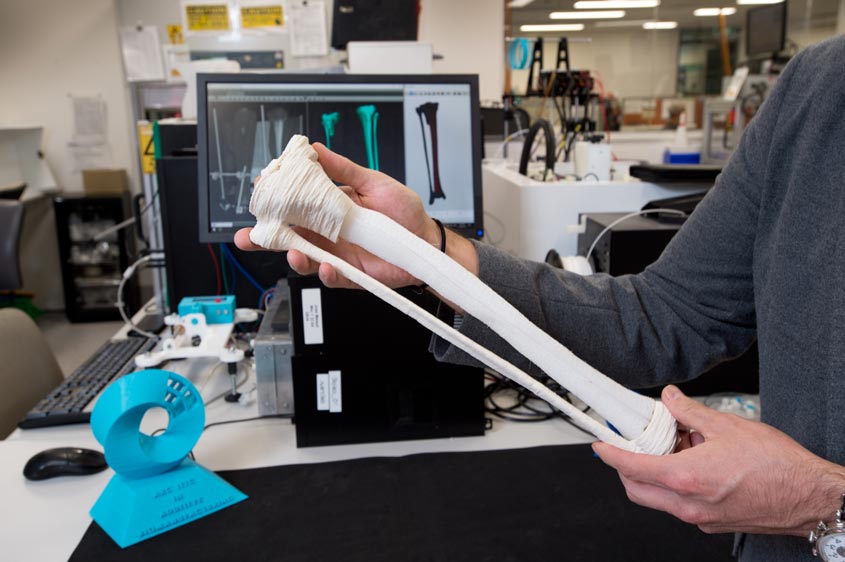

While personal 3D printing has not developed as anticipated, there has been a rise in a number of other forms and modes of 3D printing. Industrial 3D printing – along with robotics and Big Data – has become integrated into advanced manufacturing. Information technology and design companies have sought to improve the applications of 3D printing. Metal 3D printing has attracted significant investment – particularly from transportation companies. There also has been much experimentation with health applications of 3D printing – such as dental 3D printing, medical 3D printing, and bioprinting.

As the technology has matured and advanced, there have been a number of early pieces of litigation and some policy developments in respect of 3D printing regulation. Our recent book 3D Printing and Beyond explores some of the key developments in IP and 3D printing. In particular, it investigates 3D printing issues in the domains of copyright law, designs law, trademark law, patent law, and trade secrets (as well as some larger questions about 3D printing regulation). It also looks at the use of open licensing models in respect of 3D printing.

3D printing and copyright law

Some years ago, there was moral panic that the advent of 3D printing would lead to a Napster-like scenario of large-scale copyright infringement. While this situation has not arisen, there have been various skirmishes involving copyright law and 3D printing. For example, Augustana College in the United States objected to the 3D scanning of Michelangelo statues although these were not covered by copyright and were clearly in the public domain. United States cable and TV network HBO objected to Fernando Sosa’s 3D printed Iron Throne Game of Thrones iPhone deck. American singer-songwriter Katy Perry complained about Fernando Sosa’s 3D printed Left Shark (although the work was later reinstated to the Shapeways 3D printing systems). The estate of French-American artist Marcel Duchamp had issues with a 3D printed set of chess pieces based upon the artist’s work.

The notice and takedown system of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (USA) has been employed with respect to 3D printing. Shapeways and a number of other 3D printing firms have been concerned about the impact this regime will have on 3D printing platforms and intermediaries.

There has also been debate over the use of technological protection measures in the context of copyright law and 3D printing. For example, the United States Copyright Office has recognized a narrow exception for technological protection measures in relation to 3D printing feedstock.

3D printing and designs law

Developments in 3D printing have also given rise to the right to repair an object.

In the European Union, there has been a push for the right to repair to help support consumer rights and the development of a circular economy. In this respect, the European Ecodesign Directive (Directive 2009/125/EC) has been an important driver of change in the behavior of companies and consumers.

In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission held a hearing in July 2019 on “Nixing the Fix: A Workshop on Repair Restrictions”. There remain significant divisions between IP holders and champions of the right to repair in the United States. Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has called for a right to repair bill to benefit farmers in agricultural communities in the United States.

In Australia, there was an important test case regarding the right to repair under design law (GM Global Technology Operations LLC v S.S.S. Auto Parts Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 97). The Australian Treasury has been considering policy options for sharing repair information in the motor vehicle industry.

The ACT (Australian Capital Territory) Consumer Affair Minister, Shane Rattenbury, has called for a right to repair at the Consumer Affairs Forum, which includes Ministers from both Australia and New Zealand. The Federal Minister Michael Sukkar has requested that the Australian Productivity Commission investigate the issue.

There has also been a push for right-to-repair legislation at both state and federal levels in Canada. In this regard, Laura Tribe, Executive Director of Open Media, has argued, “we’re really making sure people have the power to own their own devices”.

3D printing and trademark law

3D printing also disrupts trademark law and related legal regimes – such as passing off, personality rights, character merchandizing, and trade dress. The legal conflict over Katy Perry’s Left Shark trademark application highlights some of the issues in this field.

In the field of bioprinting, Advanced Solutions Life Sciences has sued Biobots Inc. for trademark infringement (Advanced Solutions Life Sciences, LLC v BioBiots Inc. 15 May 2017, 2017 WL2114969). Advanced Solutions Life Sciences owns and uses the registered trademark “Bioassemblybot” for three-dimensional bioprinting and tissue fabrication.

3D printing and patent law

As WIPO's 2015 World Intellectual Property Report on Breakthrough Innovation and Economic Growth has shown, there has been a steady rise in patent applications in the field of 3D printing. A number of specialist industrial 3D printing companies – such as 3D Systems and Stratasys – have accumulated significant patent portfolios in respect of 3D printing. Major manufacturing companies – such as GE and Siemens – have also built up significant patent assets in the field of 3D printing and additive manufacturing. Information technology companies – like Hewlett Packard and Autodesk – are also notable players in the area of 3D printing.

With the rise in commercial value of 3D printing in the realm of manufacturing, there has been significant patent litigation over metal 3D printing. In July 2018, in Desktop Metal Inc. v Markforged, Inc. and Matiu Parangi (2018) (Case Number 1:18-CV-10524), a federal jury found that Markforged Inc. did not infringe two patents held by its rival Desktop Metal Inc (see Desktop Metal Inc. v Markforged, Inc. and Matiu Parangi (2018) 2018 WL 4007724 (D. Mass.) (jury verdict). In response, Greg Mark, CEO of Markforged Inc., commented, “we feel gratified that the jury found we do not infringe, and confirmed that the Metal X, our latest extension of the Markforged printing platform, is based on our own proprietary Markforged technology.” For its part, Desktop Metal noted that it was “pleased that the jury agreed with the validity of all claims in both of Desktop Metal’s patents asserted against Markforged.”

In 2018, Desktop Metal Inc. and Markforged Inc. subsequently reached a confidential financial settlement, thereby resolving all outstanding litigation between the two parties. However, in 2019, Markforged Inc. sued Desktop Metal Inc., claiming that its rival had breached the non-disparagement clause in the settlement.

3D printing and trade secrets

There has also been some early litigation in the area of trade secrets law and 3D printing. In 2016, a Florida-based startup 3D printing company, Magic Leap, sued two of its former employees for trade secret misappropriation under the Defend Trade Secrets Act in Federal Court in the Northern District of California (Magic Leap Inc. v Bradski et al (2017) Case Number 5:16-cvb-02852). In early 2017, the judge granted the defendants’ motion to strike, ruling that Magic Leap failed to disclose the asserted trade secrets with “reasonable particularity’”. The judge allowed Magic Leap to amend its disclosures. This matter was the subject of a “confidential agreement” in August 2017. In 2019, Magic Leap brought legal action against the founder of Nreal, claiming breach of contract, fraud, and unfair competition (Magic Leap Inc. v Xu, 19-cv-03445, U.S. District Court, Northern District of California (San Francisco)).

3D printing and open licensing

In addition to proprietary modes of IP protection, there has been extensive use of open licensing for 3D printing. A number of companies – like the Czech company Prusa Research; the Dutch-American company Shapeways; and Dutch company Ultimaker – have espoused an open source philosophy. The Maker Movement has relied upon open licensing to help share and disseminate 3D printing files. The State of the Commons 2017 report highlighted that Thingiverse was one of the top platforms for using Creative Commons licenses.

Other issues raised by 3D printing

In addition to matters of IP, 3D printing has also been posing a range of other legal, ethical, and regulatory issues. In the field of healthcare, regulatory authorities have grappled with personalized medicine. The United States Food and Drug Administration, and the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration have held consultations about developing well-adapted regulations for medical 3D printing and bioprinting. The European Parliament has issued a resolution calling for an holistic approach to the regulation of 3D printing.

There is also ongoing litigation in the United States over the 3D printing of guns. A number of State Attorneys-General have sued the current Administration to halt a settlement between the Federal Government and Defense Distributed. And there have been a number of criminal cases in Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States over the 3D printing of guns. Law makers are discussing whether there should be new offenses in respect of the possession of digital blueprints for making 3D printed guns.

Related Links

The WIPO Magazine is intended to help broaden public understanding of intellectual property and of WIPO’s work, and is not an official document of WIPO. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WIPO concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication is not intended to reflect the views of the Member States or the WIPO Secretariat. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WIPO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.