Japan's Innovative Contribution to Movies

May 2, 2014

To celebrate this year’s World IP Day theme – Movies: A Global Passion – the WIPO Japan Office takes a look at some of the innovations in film that have come from Japan and the contributions they have made to the movies we love.

A rich heritage

Japan’s passion for movies has its roots well in the past. Long before the cinematograph – developed and patented by the Lumière Brothers – was introduced to the country in 1897, the Japanese were using moving images in the form of utsushi-e, created by magic lanterns or jidō gentō (which used mirrors and a light source combined with glass slides).

The introduction of the cinematograph, however, triggered the rapid development of Japan’s film industry. For most of the first half of the twentieth century, the country’s movies were heavily influenced by traditional Japanese theater, such as kabuki (a classical drama that includes dance). In fact, before movies with sound – so-called “talkies” – were developed, the Japanese film industry took cues from kabuki, using enthusiastic benshi (narrators) and a band of musicians for music and sound effects, all performed live in the cinema during the film. Such popular performances continued to attract sizeable audiences into the early 1940s, well after “talkies” were introduced.

Japanese film adds value to national economy

Eventually benshi were replaced with integrated sound and musical scores, and as Japanese directors, screenwriters, producers and actors became more proficient in their craft, the Japanese film industry expanded and matured. Today, the industry contributes over US$65 billion annually to the Japanese economy, employing over 88,000 people and accounting for 0.53 percent of the country’s GDP.

Other economic spin-off benefits include the many lucrative licensing and merchandizing agreements that flow from protecting film elements such as movie titles and characters as registered trademarks. Similarly, product placement agreements underpinned by trademark protection are becoming an increasingly popular and persuasive vehicle for advertising and marketing, boosting demand for featured consumer products. Film locations also make significant contributions to the local economy, as hot tourist destinations. This indirect income adds over US$70 billion per year to the Japanese economy, benefiting industries such as tourism, manufacturing, hospitality and transport.

Innovative techniques

Yasujirō Ozu (1903-1963), considered by many to be one of Japan’s greatest film directors, developed a number of innovative techniques that are still used today. When he first started in the industry, movies were typically filmed from the vantage point of the camera operator’s shoulder. This gave viewers a sense that they were looking onto a scene from afar. To create a more intimate viewing experience, Yasujirō Ozu adopted a new approach. By placing the camera about 60 centimeters from the ground, he gave viewers the feeling of being at the center of a scene. The technique soon caught the imagination of his peers and is still commonly used in the film industry both within Japan and beyond.

The pioneering director developed two further innovations that have become common features of film production throughout the world, namely the use of ellipses and static transitions. As in literature, ellipses are a way to fast-forward an element of the storyline without actually having to show it. For example, a filmmaker can capture the idea of a town festival without actually shooting the event by simply juxtaposing one scene that shows the population of a town preparing for a festival, and another that shows the townspeople cleaning up the following day. Ellipses are commonly used to leave out certain events that are not crucial to the storyline, but Yasujirō Ozu was well known for using ellipses in a stylistic way by omitting major developments, leaving the audience to infer what happened.

The next time you watch a movie, pay close attention to the transitions. How many times does a transition fade, and how many times is a static image, such as a shot of a building or a panoramic view, used? The use of static images to transition from one scene to another (rather than using fade-out shots) was a hallmark of Yasujirō Ozu’s work. As his films were screened around the world, other filmmakers adopted the technique. The Belgian film director, Chantal Akerman, for example, was one of the first outside of Japan to adopt Yasujirō Ozu’s techniques. The result was the acclaimed 1975 production, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, which also brought Yasujirō Ozu’s innovative filming techniques to new audiences.

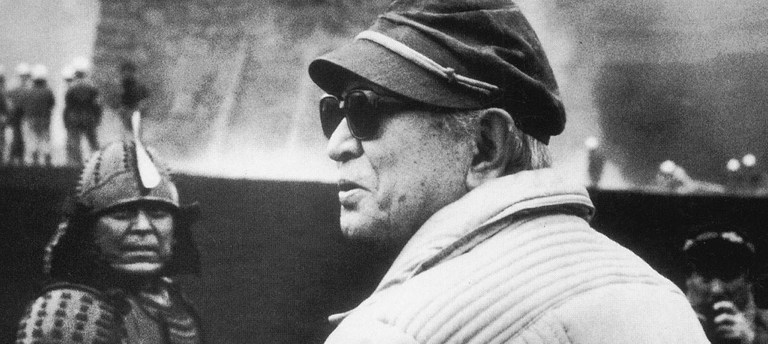

The Japanese producer, screenwriter, editor and director, Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998), regarded as one of the most influential filmmakers in the history of cinema, also helped shape the global film industry. His attention to detail, especially in his period films (jidaigeki), where he insisted on authentic sets, realistic props and meticulously edited screenplays, took Japanese filmmaking to new levels. His bold, dynamic style and his disruptive depiction of screen space through the use of multiple camera set-ups sealed his international reputation as a master of film. In his films, he explored the complexity of the master-student relationship, class division, and the journey and awakening of the hero. His work has inspired filmmakers in Hollywood, such as Robert Altman, Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese. George Lucas, for example, was so impressed that he drew upon Kurosawa’s 1958 film, The Hidden Fortress, as inspiration for the first Star Wars (1977) film.

Creating new genres

Japan’s unique, homegrown animated movies known as anime have produced some of the country’s most successful movies. The evolution of the technologies used to make movies has created the means to bring Japanese comic books, or manga, to life on the screen. Box office hits such as Momotaro’s Divine Sea Warriors (1945), Japan’s first full-length anime feature film, and Spirited Away (2001) by Hayao Miyazaki, have been exported to fans across the world. Today, anime accounts for over 25 percent of Japanese film industry revenue, and lucrative licensing deals underpinned by IP rights bring in additional revenue. Licensing a popular anime series, such as Tokyo Majin and Kurai: Phantom Memory, can bring in nearly US$1 million per episode. Such revenues support the ongoing creation of anime for a worldwide audience. Two sub-genres of anime, kaiju (monster) and mecha (robots), have enjoyed long-standing popularity and have also inspired many films by major international studios, including Ultraman (2004), Cloverfield (2008), and Pacific Rim (2013), as well as numerous interpretations of the classic Japanese Godzilla film series.

Testing technical limits

Beyond the Japanese film industry’s cinematographic influence, the country’s inventors have helped transform the equipment used in movie production. Over the years the quality of screens has improved, achieving ever-higher levels of resolution. In the 1900s, movie screens had on average 4,000 pixels per image (ppi), whereas today high definition screens with resolutions of over 2 million ppi are common. Japanese innovators have also supported the move away from celluloid to the use of digital technology for movie making. The Japanese company Sony, for example, was an early innovator in high-resolution film cameras and its equipment was used to film Julia and Julia (1987), one of the world’s first high-definition movies. With the transition to digital cameras, Japanese companies such as Sony, Panasonic, Canon, and JVC have created both high-end digital cinema cameras used by major production studios, and lower cost products that are accessible to and affordable for independent filmmakers. These smaller, cost-effective digital cameras are increasingly used by studios for point-of-view scenes in tight spaces. Canon cameras were used to shoot such scenes in the 2012 superhero blockbuster The Avengers.

Japanese companies such as Matsushita, Sony, and Toshiba developed some of the first memory card technology used to store digital footage. New camera lenses to capture high-resolution, digitally filmed scenes have also been developed in Japan. With patent-protected technologies such as these, creators in Japan support the technological evolution of filmmaking and help to further enhance the movie-going experience.

Innovation: fueling the evolution of cinema

While filmmakers from other countries have adopted many Japanese film innovations, those in Japan also continually pay attention to their international counterparts, taking note of new technologies, styles, and designs – such as film dollies, lighting equipment, makeup, set construction, and physical film types – for use in their own filmmaking.

When new technologies and designs originating from abroad were first imported and combined with traditional Japanese stories and filming techniques in the 1950s, the country’s film industry began producing movies that soon earned international recognition. They enabled moviegoers outside of Japan to delve into an exotic world. The enhanced technical quality of these films resulting from the use of imported innovations allowed Japanese filmmakers to compete with popular movies from other countries.

One of the first successes resulting from the marriage of domestic and foreign technology and techniques was the 1953 award-winning Jigokumon (Gate of Hell), which also won the Palme d’Or at the 1954 Cannes Film Festival and an Academy Honorary Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 1955 Academy Awards in the USA. Jigokumon signaled a new era for the Japanese film industry which went on to produce many high quality films with international appeal, such as Seven Samurai (1954), the Godzilla series (1954-2004), Ran (1985), Battle Royale (2000), Departures (2008), and The Wind Rises (2013).

A new landscape for film

Japan has a rich history of innovation in film. The incentives inherent in the IP system have helped to fuel this tradition and to spur the industry’s growth. Japanese filmmakers have made a significant contribution to the global film industry both in the way films are produced and also by enriching the quality and type of films available to the viewing public. Thanks to the IP system, the large number of creators - screenwriters, actors, musicians, directors - involved in filmmaking are able to earn a living from their work; and producers, whose vision and enthusiasm are key to getting a film project off the ground, can attract the investment needed to make a film and secure distribution agreements to ensure that the film reaches the widest possible audience. Japanese innovators, creators and filmmakers have without doubt added impetus to the global passion for movies and made a lasting impact on international cinema.