10.2.1 United States Patent and Trademark Office

The USPTO examines patent applications and issues patents. The patent examination procedures are set forth in the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure.32

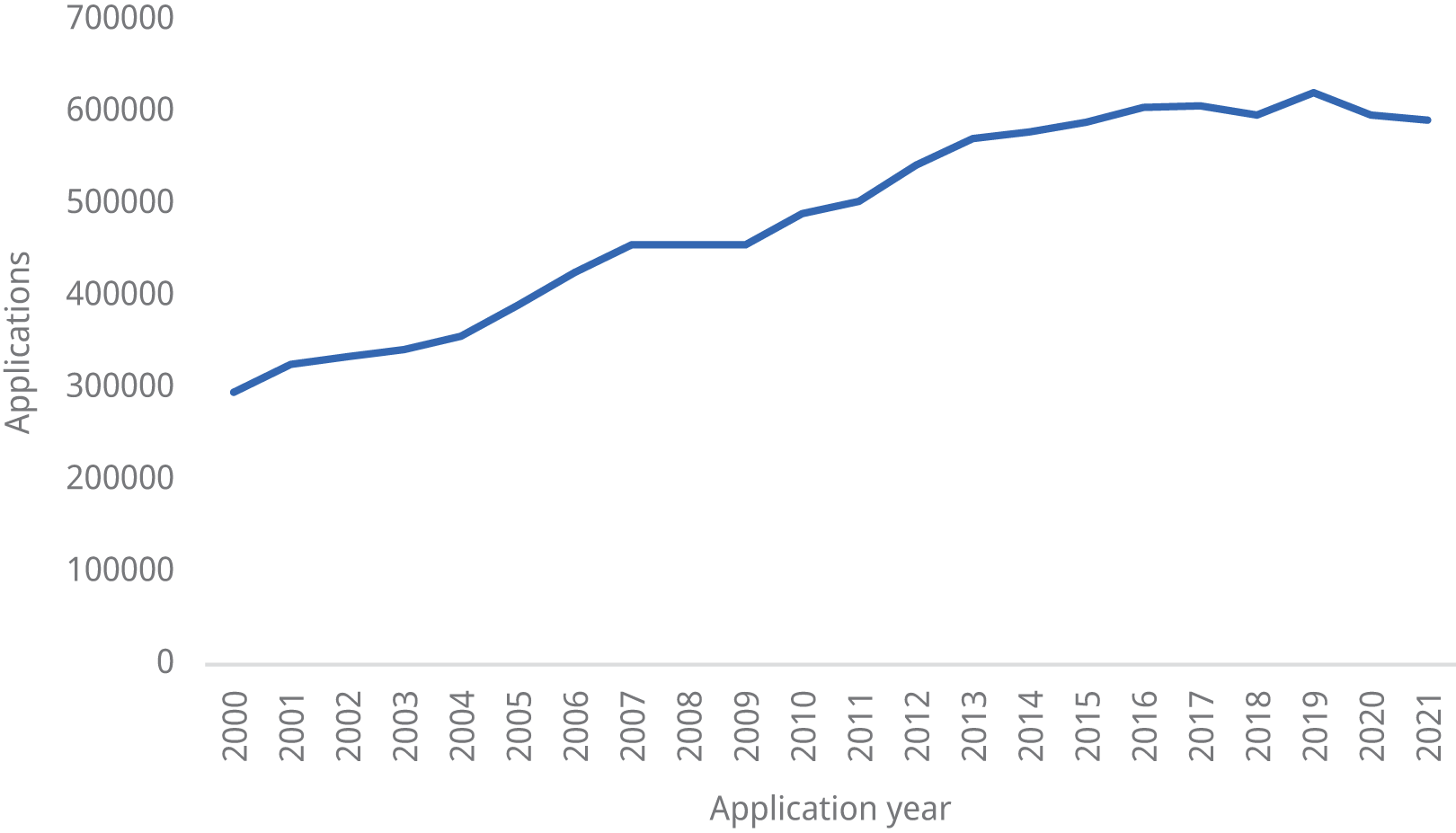

Figure 10.1 shows the total number of patent applications (direct and Patent Cooperation Treaty national phase entry) filed with USPTO from 2000 to 2021. In 2021, the USPTO received 591,473 patent applications, a significant increase over the 425,966 applications filed in 2006.

Source: WIPO IP Statistics Data Center, available at www3.wipo.int/ipstats/index.htm?tab=patent

Although the U.S. patent system has authorized the USPTO to correct defects and adjust patent scope through a reissuance process,33 Congress did not authorize the USPTO to reexamine or revoke patents until 1980. As a result of the AIA, administrative patent review is now a robust and commonly used mechanism to challenge patent validity.

In 1980, Congress established an ex parte (one party) reexamination process that enabled patent owners or third parties to request the USPTO to review the validity of issued patents.34 The review process was limited to the review of novelty and nonobviousness based on a limited range of prior art (patents and printed publications). The process was conducted ex parte – that is, only the patent owner participated in the proceeding with the USPTO.

For several reasons, the ex parte reexamination process was only rarely invoked. For example, it often took years to complete. As a result, district courts were reluctant to stay enforcement proceedings pending completion of reexamination. Furthermore, many potential challengers perceived that the process was tilted toward upholding validity. Consequently, most accused infringers did not consider ex parte reexamination to be a viable alternative to litigation.

In 1999, Congress established a more balanced inter partes (between parties) reexamination procedure that allowed third-party challengers to comment on patent owner responses.35 This process, however, also failed to gain much traction: it was slow and barred challengers from raising any ground that could have been raised during the reexamination in subsequent civil litigation.

The bursting of the dot-com bubble in March 2000 caused start-ups to declare bankruptcy, resulting in their software and internet-business-related patents being put up for auction. A new breed of patent-assertion entities scooped up these assets and pursued a wave of nonpracticing entity lawsuits. The havoc wrought by these cases, some of which threatened to enjoin substantial business units, spurred technology companies to pressure Congress to reform many aspects of the patent system. Amid this turmoil, in 2005 the USPTO established the Central Reexamination Unit (CRU), which expedited reexaminations and resulted in greater usage of the USPTO’s reexamination processes. Nonetheless, district courts were still reluctant to stay parallel cases, leading to costly duplication of administrative and judicial resources.

Passing comprehensive patent reform proved difficult. As the Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit addressed some of the thornier issues, such as tightening the standard for obtaining injunctive relief and the nonobviousness standard, Congress focused its reform on a less controversial issue: administrative patent review. Following the logic of patent oppositions in the European Patent Office, Congress expanded and expedited administrative patent review as a key component of the AIA.

The AIA established three principal review procedures: (1) inter partes review (IPR) – which replaced inter partes reexamination with a streamlined and more robust review process;36 (2) covered business method review – a transitional review proceeding focused on weeding out dubious business method patents;37 and (3) post-grant review (PGR).38 The AIA left ex parte reexamination in place.39 It also established supplemental examination – an expedited procedure for the USPTO to consider, reconsider or correct information believed to be relevant to the patent40 – and it added a special proceeding (derivation proceeding) for determining whether a patent application “derived” a claimed invention from another person or persons and whether it was therefore patentable by that applicant.41 Covered business method review expired in September 2020. The AIA left the CRU in place; it now handles patent reissuance, ex parte reexamination, and supplemental examination.

10.2.1.1 Representation at the United States Patent and Trademark Office

To represent parties at the USPTO – including in patent review proceedings – a practitioner must be a member of the Patent Bar.42 To qualify for membership, a person must possess the requisite scientific and technical training and pass the Patent Bar examination, which tests an applicant’s knowledge of patent law and procedures.

10.2.1.2 Central Reexamination Unit

As noted above, the USPTO established the CRU in 2005 to expedite and elevate the credibility of ex parte and inter partes reexaminations. The CRU is staffed with senior primary patent examiners and supervisory patent examiners, who have a wide range of technical expertise and advanced patent legal knowledge.

The AIA supplanted and augmented the prior administrative review processes. Most importantly, the AIA replaced inter partes reexamination with a streamlined and expeditious IPR, which is handled by the PTAB (see Section 10.2.2.4). The AIA retained ex parte reexamination with the CRU with modest adjustments. It also added supplemental examination, a post-grant proceeding that provided patent owners with a new process for requesting supplemental examination of an issued patent to “consider, reconsider, or correct information” believed to be relevant to the patent. In 2014, the USPTO transferred the responsibility and oversight for all reissue applications to the CRU.

10.2.1.3 The Patent Trial and Appeal Board

The AIA significantly expanded the USPTO’s patent review authority through its establishment of several review proceedings under the auspices of the PTAB, a new review authority within the USPTO. The PTAB is divided into an Appeals Division and a Trial Division. The Appeals Division handles appeals of patent examiner rejections, with specialized sections adjudicating different technology areas. The Trial Division handles contested cases such as IPRs, PGRs, and derivation proceedings. The PTAB employs approximately 200 Administrative Patent Judges (APJs), who have scientific or engineering technical training as well as legal training and patent litigation experience.

Most importantly, the AIA replaced inter partes reexamination with a streamlined, expeditious IPR trial proceeding that can be pursued at any time after nine months following the patent grant.43 Within a few years of the AIA’s passage, IPRs reshaped the patent enforcement landscape. The IPR mechanism for challenging patent validity proved popular among accused infringers. In its first full year of operation (2012), the PTAB received over 1,000 petitions. The PTAB instituted reviews for over 80 percent of these petitions and invalidated many of the reviewed claims. The institution and invalidation rates have since leveled off. Of the 13,927 IPR petitions filed through October 2022, the PTAB instituted review of approximately 60% of the petitions challenging 8,578 patents. The PTAB has invalidated at least one claim in 2,749 of those patents and fully invalidated 890 patents.

The AIA also added PGR, a patent challenge that is available within nine months of patent issuance.44 Although broader in scope than an IPR, PGR is not widely used due to its high cost and uncertain benefits. The IPR provides a more certain potential benefit: revoking a patent asserted against the challenger.

With the shift to a modified first-to-file novelty standard, the AIA provided for derivation proceedings to adjudicate inventorship disputes.45 These proceedings replaced interference proceedings, which more commonly arose when the United States used a first-to-invent novelty regime. Derivation proceedings have been relatively rare.