6.6 Judicial patent proceedings and case management

6.6.1 Key features in patent proceedings

As in all civil cases, the onus of proving infringement is on the plaintiff suing for infringement.128 The court may shift the evidentiary burden and call upon the defendants to establish the noninfringement of process claims in specific circumstances consistent with Article 34 of the TRIPS Agreement. Section 104A of the Patents Act, 1970, provides for two situations in which the defendant can be asked to prove noninfringement of a process claim. One condition precedent common to both situations is that the defendant’s product must be identical to the product directly obtained by the patented process. Once this condition is fulfilled, the court retains the power to demand that the defendant prove noninfringement if the process is for obtaining a new product129 or if the plaintiff shows a substantial likelihood that the defendant is using the patented process and is unable to determine the defendant’s process despite reasonable efforts.

The court may not require the defendant to disclose its process if such disclosure would result in the disclosure of any trade, manufacturing or commercial secrets that form part of the defendant’s process, but only if the disclosure appears reasonable to the court.130 The use of confidentiality clubs, however, may aid even in such disclosure.131

6.6.2 Forum and locus standi to initiate infringement actions

A patent enforcement action under Section 104 of the Patents Act, 1970, can be initiated before a district court or higher. The court will try a patent suit as a commercial suit under the Commercial Courts Act, 2015.132 This also applies to a suit seeking a declaration of noninfringement.133 However, if a defendant in an infringement action counterclaims the patent’s invalidity, the suit and the counterclaim are automatically transferred to the High Court for further adjudication.134 A declaratory suit for noninfringement cannot question the patent’s validity.135The registered owner of the patent, or the assignee thereof, is entitled to sue for infringement. Section 109 of the Patents Act, 1970, provides that an exclusive licensee may sue for patent infringement but must implead the patent’s registered owner as a defendant. Under Section 110 of the Act, a person who has been granted a compulsory license may also sue for patent infringement if, upon notification of infringement to the patentee, the patentee fails to take action within two months.

6.6.3 Early case management

Once all pleadings are complete, the suit is listed before a designated commercial court single-judge bench in a case management hearing for framing issues. The court identifies, as precisely as possible, the issues that arise for determination; directs the filing of witness statements; and sets the schedule for trial. The Commercial Courts Act, 2015, prescribes short time limits for completing pleadings. Pending interim applications do not (and should not) delay the case management hearing for framing issues.

6.6.3.1 Pleadings and overall case schedule

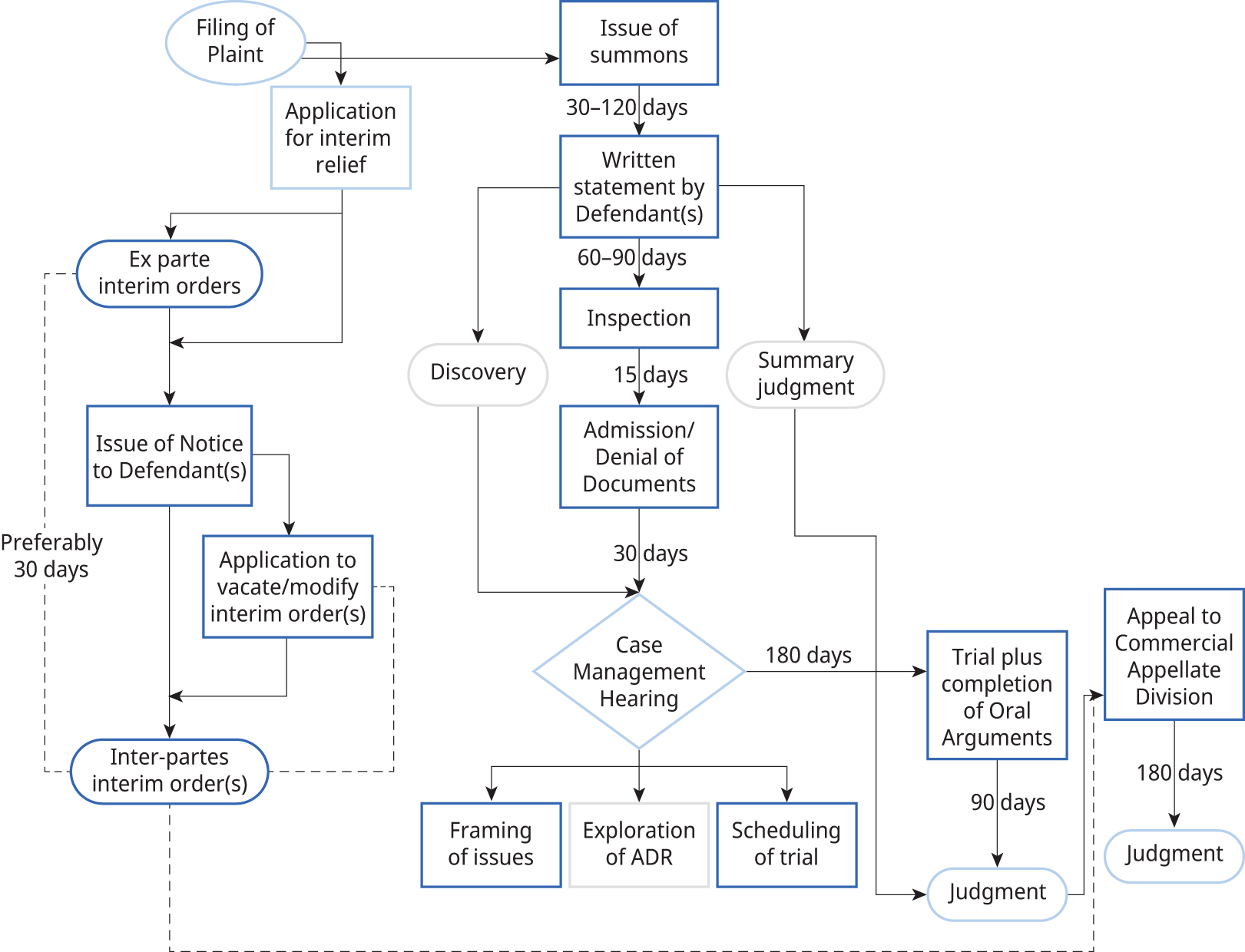

The Commercial Courts Act, 2015, fixes mandatory timelines for filing all pleadings. The Supreme Court of India, in SCG Contracts India Pvt. Ltd v. KS Chamankar Infrastructure Pvt. Ltd,136 confirmed that the timelines fixed under the Act are mandatory. The Act also prescribes a schedule for the entire case (see Figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4 Overall case schedule according to the Commercial Courts Act, 2015

Note: ADR = alternative dispute resolution.

The rigidity of timelines under the Act has been of some concern in patent litigation, given the technical complexity involved. However, most practitioners and litigants agree that, without fixed timelines, litigation tends to become unnecessarily protracted. The strict scheduling ensures that pleadings are completed on time and that trials are expedited. The real bottleneck is the final arguments post-trial, which has systemic causes: chiefly, the enormous number of unfilled positions of judges. Recent trends in filling these vacancies, coupled with specialized training in IP-related matters of judges rostered to IP cases, ought to address the bottleneck problem.

6.6.3.2 Case management hearing

Case management is mandatory under the Commercial Courts Act, 2015. The first case management hearing must be mandatorily held not later than four weeks from the date of filing of an affidavit of admission or denial of documents by the parties. It is intended for the court to engage in the early identification of disputed issues of fact and law, the establishment of a procedural calendar for the entire case (including trial and final hearing), and the exploration of the possibility of dispute resolution other than by trial.

6.6.4 Provisional measures

As a common-law jurisdiction, Indian courts are vested with extensive discretionary powers to grant interim relief. The usual determinants apply: whether the plaintiff has a prima facie case, where the balance of convenience lies, and to whom irreparable injury is likely if the order is or is not granted. An interim order may subject the plaintiff to conditions, including security. Injunctions can be tailored to suit the remedy.137

In general, interim reliefs can be in various forms, including interim injunctions; Mareva orders or freezing orders; Anton Piller orders, where local commissioners (LCs) are appointed with powers of search and seizure; and directions for keeping accounts. Under Order XXXIX(1)–(2) of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 [hereinafter the “Code of Civil Procedure”], patentees may also seek interim and ad interim injunctions. Indian courts have regularly considered the grant of interim injunction orders, Anton Piller orders, Mareva orders, Norwich Pharmacal orders or John Doe orders in fitting cases.

It is usual to seek even ex parte ad interim relief in suits for patent infringement. In some cases, where the patent has been tested multiple times in litigation, courts usually even grant the ad interim injunction ex parte; there is no strict rule. For instance, in the case of SEPs, defendants are usually called upon before the grant of an injunction for a response as to whether they are willing to take a license on fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms.

Irrespective of the outcome of the interim proceedings, the parties (usually the unsuccessful party at the interim stage) usually seek an expeditious trial and final hearing. In fact, in one case where the interim injunction was granted in favor of the patentee (i.e., Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. v. Glenmark Pharmaceuticals),138 the Supreme Court allowed the sale of the existing stock already manufactured by the defendant and directed a day-to-day trial, saying that this was in the national interest, one that demanded a suitable commercial environment for the immediate resolution and adjudication of contentious commercial cases.139 In that case, due to the intervention of the Supreme Court, the time from the suit’s filing to final judgment was only about 30 months. The trial concluded in a record time of less than 30 days. Final arguments were heard for three weeks, and judgment followed very soon thereafter. The Supreme Court has also issued general directions for such expedited hearings in other patent matters.140

In cases where a patent has been tried and tested in prior litigation, courts have not hesitated to grant interim injunctions, though the defendant may be permitted to exhaust existing stocks along with accounts. Some perceive the Delhi High Court to be quite liberal in granting interim injunctions to patentees, though there have been some instances in which the court has refused interim injunctions owing to the complexity of the invalidity defense. In other cases, the court has crafted alternative arrangements for the interim period. Where an interim injunction is refused, courts almost always direct the defendant to maintain and file accounts.

6.6.4.1 Governing legal standards and burdens

Courts see growing numbers of patent litigation, with a corresponding increase in the grant of injunctions (both permanent and interlocutory). Temporary injunctions are regulated by Sections 94 and 95 and Order XXXIX of the Civil Procedure Code. The substantive law on temporary and perpetual injunctions can be found in Sections 36–42 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963.

The general principles for grant or denial of such interim orders are well known: a prima facie case, the balance of convenience, irreparable injury and public interest factors.141 Indian courts have derived principles following the decision of the House of Lords in American Cyanamid v. Ethicon Ltd,142 though the Supreme Court of India has observed that the relatively diluted standard of “prima facie case” in American Cyanamid will not apply in India.143 Similarly, whereas American Cyanamid suggests that more weight must be attached to patents granted after a detailed examination procedure, Section 13(4) of the Patents Act, 1970, and some judicial precedents in India suggest that this proposition is inapplicable to Indian patent law.144

6.6.4.1.1 Prima facie case

The prima facie case requirement is used to discern whether the plaintiff has a reasonable case on merits. It does not finally or conclusively decide issues of fact. It weeds out frivolous or vexatious claims – ones manifestly without merit. As part of this assessment, courts also assess whether defendants have a credible challenge to the suit patent’s validity.145

Initially, in India, a few judicial pronouncements referred to a six-year rule (i.e., a presumption that there could be an increased probability a patent could be treated as valid on the expiry of six years from the date of grant). The genesis of the six-year rule approach can be traced to the Madras High Court’s ruling in Manicka Thevar v. Star Ploro Works case,146 which was subsequently picked up in other judgments.147 However, none of the provisions of law appears to suggest or support this numerical fixation with six years. The Manicka Thevar case was subsequently held not to be correct law by another division bench of the Madras High Court.148 In F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd v. Cipla Ltd, a single judge of the Delhi High Court also held that there was no basis for the six-year rule and rejected the application of the said rule in patent cases.149 Thus, one will not find a discussion of any such six-year rule in most recent patent cases across India.

6.6.4.1.2 Balance of convenience and public interest

The second requirement for the grant or denial of an interim injunction is that the balance of convenience must be in favor of granting an injunction. The court, while granting or refusing to grant an injunction, should exercise sound judicial discretion to compare and determine the amount of mischief or injury likely to be caused to the respective parties if the injunction is refused and if it is granted. The court would weigh competing possibilities or probabilities.

In India, public interest has been recognized both as a separate factor and as a factor read into the test for the balance of convenience.150 For instance, the public interest in enabling access to lifesaving drugs (both supply and pricing considerations) has been considered a relevant factor when deciding on an application for an interim injunction.151 Recently, given the influence of comorbidity factors such as diabetes and obesity in the severity of COVID-19 infections, the pricing of antidiabetic medications was considered one of the relevant factors when assessing interim injunction applications.152

The defense of public interest is not a complete exception to a legally valid patent and must not be too broadly interpreted, as it would undermine “the rights granted by the sovereign towards monopoly.”153 The Delhi High Court has recognized that upholding the enforcement of patents is also in the public interest.154 Thus, often, public interest factors are considered along with the prima facie strength of the infringement case or the invalidity defense.155

Public interest forms part of the matrix considered by the court and need not always be a dispositive factor in every case. For instance, in Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH v. Ajanta Pharma Ltd,156 factors such as loss of employment and revenue earned by the state – even in cases where the patented drugs were not of a lifesaving nature – were considered by the Delhi High Court. However, in a subsequent decision, Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH v. BDR Pharmaceuticals International Pvt. Ltd,157 another judge of the same High Court held that the export of non-lifesaving drugs would not qualify under the test of public interest merely due to encouraging economic activity and the country earning foreign exchange revenue.

The Delhi High Court, in Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. v. Glenmark Pharmaceuticals,158 invoked several equitable principles to guide the exercise of discretion in granting injunctions. These included an assessment of the parties’ conduct, whether the defendant attempted to clear the way by filing oppositions or seeking revocation, and so on.

It is also common for defendants to raise pleas of nonworking of patents or nonfiling of working statements to defend against interim injunctions as part of the balance of convenience and public interest factors. The working requirements under the Patents Act, 1970, are stringent. The legislative history shows that the nonworking of patents by foreign companies was one of India’s most significant concerns when drafting the legislation. In a case concerning a patented respiratory disorder drug, the Delhi High Court, in Cipla Ltd v. Novartis AG,159 held that the mere nonmanufacturing of sufficient quantities in India alone could not result in the denial of an interim injunction. However, defendants are free to apply for a compulsory license in such cases. There is an earlier opposing view suggesting that the nonworking of a patent could lead to denial of injunctive relief.160 The later view in Cipla is now the more prevalent view. Though no compulsory license was granted during the COVID-19 pandemic, in dealing with cases relating to shortages of essential medicines used in the treatment of COVID-19, both the Supreme Court and the High Court have made observations favoring such steps being taken by the Government.161

6.6.4.1.3 Irreparable injury

The third and equally important consideration is the condition of irreparable injury. This refers to the patentee having no other remedy available other than an injunction. Irreparable injury, however, does not mean that there must be no physical possibility of repairing the injury. Instead, it means only that the injury must be a material one – namely, one that cannot be adequately compensated in damages.

In Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. v. Glenmark Pharmaceuticals,162 the Delhi High Court recognized that, in cases where the patentee has been the sole supplier of the patented technology, allowing a defendant to enter the market may cause irreparable injury.

6.6.4.2 Other preliminary reliefs

6.6.4.2.1 Local commissioners

Order XXVI(9) of the Code of Civil Procedure provides for the appointment of LCs. Such LCs are appointed upon the establishment of a strong prima facie case. In cases of a patent infringement action, LCs have been appointed by the Indian courts to record evidence.

An order for the appointment of an LC is usually made in patent litigation if, for example, the manufacturing processes need to be ascertained. The LC is then appointed by the court with strict terms and conditions. Typical conditions imposed include:163

-

that the LC visits the premises of the defendant or plaintiff, as the case may be;

-

that the LC ascertain the manufacturing process being used, including inspection of the raw material registers, excipient data, the quantum of manufacturing and so on;

-

that the accounts of manufacture, sales and so on are inspected;

-

that the LC visits the Customs authorities to retrieve samples of alleged infringing products;

-

permitting the LC to take photographs and videotape the proceedings; and

-

permitting party representatives to accompany the LC, including counsel, to render assistance.

At the end of the execution of the commission, a memorandum of proceedings is prepared by the LC, recording the chronology of events that transpired in the commission and the observations of the LC. This is signed by the LC and the parties, and the LC must give copies of the same to each party. Thereafter, a report is filed before the court, giving a full account of the proceedings. Such a report filed by the LC can be read in evidence without the statement of the LC being recorded in terms of Order XXVI(14)(2) of the Code of Civil Procedure. So long as the court can confirm that the report is genuine and authentic, it forms part of the record. Parties may have objections to the contents of the LC’s report, in which case they can file objections. The objections are then adjudicated by the court before the report is fully read as evidence.

The LC so appointed is not performing a judicial act but a “ministerial act.” Nothing is left to the discretion of the LC, and there is no occasion to use judgment or adjudicate the issues involved. The LC only notes details and reports the actual state of affairs. The LC cannot decide the dispute, but their report helps the court in doing so.164 In short, the LC’s report is one of fact-gathering, not adjudication or determination.

6.6.4.2.2 Interim deposits and other ad interim arrangements

The interim injunction stage may become protracted owing to the technical issues surrounding patents. In such instances, and in a fitting case, courts usually put in an ad interim arrangement. In general, courts enjoy extensive discretion to mold the interim relief to suit the circumstances. For example, courts have directed interim deposits by defendants in SEP cases or have directed the submission of bank guarantees or some form of security to secure the plaintiff’s interest.165 In the recent non-SEP case of Communication Components Antenna Inc. v. Ace Technologies Corp.,166 the High Court’s interim direction to secure the plaintiff by way of a deposit of royalties and bank guarantee was upheld by the Supreme Court of India.167

Equally, in such cases of interim deposits, courts have required the patentee to furnish surety bonds for the amount received on a quarterly basis with advance copies.168

6.6.5 Discovery and gathering of information

At or before the case management hearing, it is usual for parties to admit and deny the respective documents filed by the other party and to also seek discovery, inspection or the production of documents from the other party.169 Upon an appropriate application by one party, the court may direct the other party to respond to written interrogatories on affidavit,170 permit the inspection of documents relied upon or referred by the other party,171 allow discovery of relevant documents on affidavit,172 or direct the production of documents.173

Courts are always empowered to dismiss the suit or defense for want of prosecution if a party does not comply with an order to answer interrogatories or the order for discovery, inspection or the production of documents.174 For instance, in SEP cases, the defendants or the plaintiff would be made to share the claim-mapping charts as part of the exchange of documents to prove that the patents map the standards for which they are sought to be enforced.

Often, discovery and inspection procedures are used to seek irrelevant information and protract litigation. For instance, defendants may seek entire file wrappers from all jurisdictions just as a matter of course. However, courts do not permit such a roving inquiry or fishing expedition, and the party concerned is entitled to move the court to curtail the kind of information or type of documents being sought. The other side of this is “data-swamping” or “data-flooding,” whereby a party against whom disclosure is ordered inundates the other party with all manner of documentation in an attempt to bury the crucial material in a mountain of irrelevance. The Code of Civil Procedure enables parties to seek and defend against any discovery tool, with the courts being the final arbiter if disputes arise in this context. Again, this process demands judicial time (and enough human resources on the bench) and well-honed forensic skills on all sides.

Courts also retain wide discretion in directing the production of documents under certain conditions. To enable discovery and inspection of license agreements, manufacturing processes followed and so on – which may be confidential – courts usually constitute confidentiality clubs to maintain the confidentiality of the information disclosed.175 There has been recent debate as to whether litigants can be part of these confidentiality clubs.176 However, as far as the constitution of the clubs is concerned, there appears to be no dispute; the confidentiality club, once constituted, considerably streamlines the process of discovery and inspection of documents.

Recently, the High Court of Delhi Rules Governing Patent Suits, 2022 have been notified. These rules provide for a minimum mandatory content for pleadings in patent suits,177 a minimum set of mandatory documents to be filed by the parties,178 and specific tweaks in patent suit procedures. For instance, in addition to regular pleadings, the rules provide that parties be allowed to file claim construction, invalidity, infringement briefs and technical primers based on which the court is to frame issues in the first case management hearing.179 A second case management hearing is provided for streamlining the recording of evidence, including the protocol for a hot-tubbing mechanism.180 A reserve third management hearing is provided to address any pending pre-trial concerns.181 Importantly, the rules contemplate the creation of a panel of scientific experts to assist the court.182 While setting the calendar and protocols for a final hearing, the court may also direct that a technical expert of each party may also be present to assist the court.183

6.6.6 Summary proceedings

The Commercial Courts Act, 2015, through its amendment to the Code of Civil Procedure, permits parties to seek summary adjudication.184 Either party may seek such summary disposal if the other party has no real prospect of succeeding and if there is no other compelling reason why the claim should not be disposed of before recording oral evidence.185

Such summary adjudication under Order XIII-A of the Code of Civil Procedure can be sought by filing a specific application and setting out the specific grounds.186 The application is to be filed before issues are framed.187 When adjudicating such an application for summary disposal, courts enjoy broad discretion to pass a variety of orders, including, for instance, conditional orders that require the deposit of money or furnishing security.188

Another possibility of summary disposal is under Order XII(6), by which the court is empowered to pass judgment based on admissions of fact made either in the pleading or even otherwise. The admissions made by patentees during prosecution, whether in India or any foreign jurisdiction, can be construed as admissions under the Code of Civil Procedure and result in summary disposals. The logic is straightforward and self-evident: no patentee should be permitted to make conflicting claims in different jurisdictions. A patentee must be held to be bound by statements made with regard to that specific patent claim, irrespective of where and when that claim is made. This is a species of estoppel.

Such summary procedures help the court to considerably narrow the scope of controversy. For instance, in negotiations for licensing, defendants usually admit that they need the license, and the only dispute that remains is about the licensing amount. In such suits, the court can rely on the correspondence between the parties to issue summary judgments.

Similarly, such summary adjudication has proved workable in SEP litigation: for example, where an ex-licensee of the SEP has refused to renew the license due to a failure of commercial discussions. The dispute is then restricted only to the monetary claim of the licensing fee, and other issues, such as infringement or validity, do not arise. While an ex-licensee is not estopped or precluded from challenging the validity of a patent at any time, courts are reluctant to entertain validity challenges when an erstwhile licensee elects to challenge the patent’s validity only at the time of a license renewal agreement after having enjoyed a license for several years. A court will permit such a challenge to proceed only on a demonstration of some glaring fact that goes to the root of validity and which was noticed at the time of the original licensing.

6.6.7 Evidence

6.6.7.1 Oral evidence and trial

The examination in chief (direct examination) of witnesses is compulsorily on affidavit.189 Cross-examination and reexamination (“redirect”) are taken orally live and transcribed. Often, to save the court’s time, the recording of the oral evidence is done either before the registrar of the court or before an LC. Unlike a court, LCs and registrars are not empowered to rule on objections raised during the evidence.190 However, the commissioner is entitled to enter notes they think material, about a witness’ demeanor so that the same is available to the court at the time of final hearing.191

Usually, trials take between three and five years from the date of filing to conclude, though there have been some patent cases where the trial concluded in six months to a year. Under the Commercial Courts Act, 2015, the court schedules the entire trial so that the recording of evidence is not drawn out. The trial could be day-to-day, and it is common for the courts to explicitly direct as such to reduce inconvenience to witnesses.192 Once the trial of a suit concludes, the matter proceeds to a final hearing.

It is usual for witnesses from foreign jurisdictions to record their statements through videoconferencing. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual courts and online platforms are usually used even for court hearings. Litigants can join proceedings physically, and, if the court has the facility, they can also join the hearing through a videoconferencing facility.

Witnesses are usually in-house representatives or attorneys from the respective parties who have themselves dealt with the litigation and the correspondence between the parties. A witness is not expected to have direct personal knowledge of every part of the deposition; it is enough if the witness can depose to company records and the record of the suit. In some areas, the testimony of people with personal knowledge is preferred – for example, for evidence about discussions in negotiations, the exchange of correspondence, some technical knowledge leading to the grant of the patent and so on.

Other witnesses are usually technical witnesses. In some cases, the inventor is also produced as a witness to strengthen the case of the plaintiff. Experts such as doctors, specialists, economists and accountants have also been produced in the court to establish other aspects of the litigation, such as the calculation of damages, distinguishing the prior art, mapping standards and so on. The inquiry into damages is crucial at the final stage, and, therefore, economists, financial experts or accountants who can analyze and depose to the computation of damages or royalties payable are vitally important in establishing the monetary aspect of the infringement case. Thus, the general practice is to have both in-house and expert witnesses.

6.6.7.2 Who leads evidence first? Can a defendant be directed to lead evidence first?

The Patents Act, 1970, does not specifically provide a procedure for evidence in cases of patent infringement. Instead, the procedure adopted for leading evidence in suits for infringement is in accordance with the Code of Civil Procedure193 and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Under the latter, the onus of proof is on the person making a positive assertion. Thus, the patentee-plaintiff must lead evidence first to establish infringement. The defendant leads evidence thereafter to support its defenses or its counterclaim of invalidity. However, this is not a rigid rule. In a case where the defendant admits infringement, and the only question for decision is validity, the court may direct the defendant to lead evidence first. Thus, as provided under Order XVIII, the right to begin is generally granted to the plaintiff:

- 1. Right to begin. – The plaintiff has the right to begin unless the defendant admits the facts alleged by the plaintiff and contends that either in point of law or on some additional facts alleged by the defendant the plaintiff is not entitled to any part of the relief which he seeks, in which case the defendant has the right to begin.

-

2. Statement and production of evidence. –

- (1) On the day fixed for the hearing of the suit or on any other day to which the hearing is adjourned, the party having the right to begin shall state his case and produce his evidence in support of the issues which he is bound to prove.

- (2) The other party shall then state his case and produce his evidence (if any) and may then address the Court generally on the whole case.

- (3) The party beginning may then reply generally on the whole case.

Moreover, where a process claim is asserted, depending on the facts, the burden of proof may shift to the defendant to prove non-infringement. This exceptional situation is provided for under Section 104A of the Patents Act, 1970:

Burden of proof in case of suits concerning infringement.

-

(1) In any suit for infringement of a patent, where the subject matter of patent is a process for obtaining a product, the court may direct the defendant to prove that the process used by him to obtain the product, identical to the product of the patented process, is different from the patented process if, –

- (a) the subject matter of the patent is a process for obtaining a new product; or

-

(b) there is a substantial likelihood that the identical product is made by the process, and the patentee or a person deriving title or interest in the patent from him, has been unable through reasonable efforts to determine the process actually used:

Provided that the patentee or a person deriving title or interest in the patent from him first proves that the product is identical to the product directly obtained by the patented process.

- (2) In considering whether a party has discharged the burden imposed upon him by subsection (1), the court shall not require him to disclose any manufacturing or commercial secrets, if it appears to the court that it would be unreasonable to do so.

Subject to the fulfillment of the condition precedents noted in Section 104A, this is another circumstance in which the defendant may be asked to lead evidence first.194

In Bajaj Auto Ltd v. TVS Motor Co. Ltd,195 the Madras High Court was confronted with a unique situation – a suit against the groundless threat of infringement and non-infringement against the patentee, as well as a subsequent suit for infringement by the patentee. On the limited issue of who should lead evidence first, the court held that the plaintiff in the earlier suit must lead the evidence first since the subsequent suit was more in the nature of a counterclaim of infringement by the patentee. This is yet another unique situation wherein the alleged infringer led evidence first.

6.6.7.3 Filing of affidavits of witnesses in evidence: not treated as evidence till tendered

According to Order XVIII(4) of the Code of Civil Procedure:

Recording of evidence.

-

(1) In every case, the examination-in-chief of a witness shall be on affidavit and copies thereof shall be supplied to the opposite party by the party who calls him for evidence:

Provided that where documents are filed and the parties rely upon the documents, the proof and admissibility of such documents which are filed along with an affidavit shall be subject to the orders of the Court.

- (1A) The affidavits of evidence of all witnesses whose evidence is proposed to be led by a party shall be filed simultaneously by that party at the time directed in the first Case Management Hearing.

- (1B) A party shall not lead additional evidence by the affidavit of any witness (including of a witness who has already filed an affidavit) unless sufficient cause is made out in an application for that purpose and an order, giving reasons, permitting such additional affidavit is passed by the Court.

- (1C) A party shall however have the right to withdraw any of the affidavits so filed at any time prior to commencement of cross-examination of that witness, without any adverse inference being drawn based on such withdrawal: Provided that any other party shall be entitled to tender as evidence and rely upon any admission made in such withdrawn affidavit.

As per Section 1 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, affidavits are not included in the ambit of “evidence.” Thus, typically, the affidavit of the witness goes through the process of “tendering” – the witness is put on oath and affirms the contents of the affidavit, and, thus, the affidavit contents effectively become oral evidence. Such oral evidence is normally taken into consideration by the court when facts need to be proved.

6.6.8 Experts

6.6.8.1 Role of experts and expert bodies and institutions

Although not strictly a separate institution, experts and expert bodies and institutions play a key practical role in patent matters. In this context, the Supreme Court of India, in Monsanto Technology LLC v. Nuziveedu Seeds Ltd,196 held that:

Summary adjudication of a technically complex suit requiring expert evidence also, at the stage of injunction in the manner done, was certainly neither desirable or permissible in the law. […]

[…] We are therefore satisfied that the Division Bench ought not to have disposed of the suit in a summary manner by relying on documents only, extracted from the public domain, and not even filed as exhibits in the suit, much less examination of expert witnesses, in the facts of the present case. There is no gain saying that the issues raised were complicated requiring technological and expert evidence with regard to issues of chemical process, biochemical, biotechnical and micro biological processes and more importantly whether the nucleic acid sequence trait once inserted could be removed from that variety or not and whether the patented DNA sequence was a plant or a part of a plant etc. are again all matters which were required to be considered at the final hearing of the suit.

Thus, experts and expert bodies and institutions are a critical component of proceedings where a patent’s validity is questioned. Most oppositions and revocations typically involve one or more opinions from experts or expert bodies, and the legal framework contains sufficient provisions to deal with expert opinions and evidence. For instance, under the Patents Act, 1970, the Indian Patent Office has the power to receive evidence on affidavits, issue commissions for the examination of witnesses or documents and so on.197 The Indian Patent Office may also allow any person to be cross-examined on the contents of their affidavit.198

6.6.8.2 Expert evidence under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872

The Indian Evidence Act, 1872, governs the rules of evidence applicable to enforcement proceedings under the Patents Act, 1970. It applies to all civil and criminal proceedings. This legislation has been amended and updated from time to time, including on the use of electronic documents and evidence.

Section 45 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, declares that the opinions of experts are “relevant facts.” Therefore, these opinions must be considered by courts in patent matters when forming an opinion on the point of science or art. The law only requires such experts to be “especially skilled” in the relevant area of science or art without specifying a minimum threshold. The Supreme Court of India has held that an individual could be an expert not just by the special study of the subject but also by acquiring experience in the field.199 Similar is the view of the Delhi High Court which, in a patent case where the expert witness produced did not hold a technology or engineering degree but had proven experience, held that an expert could be a person who possesses experience even if they did not have the educational qualification.200 What is relevant is whether the person is skilled and has adequate knowledge of the subject. The observation of the court reads as follows:

Be that as it may, it is accepted and recognised that a person could be an expert in an area of specialised knowledge by experience and he or she need not hold a degree in the field of specialised knowledge . A person can also become an expert by virtue of one’s avocation or occupation.201

It is generally understood that, in patent matters, the opinions of experts are critical to understanding the background in the art, as well as to appreciating the contents of the prior art and the invention. An expert could also testify as to the meaning of the terms in the claim as understood in the art. Typically, both parties to a patent enforcement action will produce such expert evidence on infringement, novelty and inventive step.

The expert will usually be highly qualified and would exceed the threshold of a person having ordinary skill in the art.

There is a view expressed that the expert in a patent matter must have personal knowledge of the prior arts,202 though this view is not correct. In law, all aspects of patent matters are viewed through the lens of a hypothetical person skilled in the art, who is normally deemed in law to automatically have knowledge of the prior arts. The correct view appears to be that the expert could testify as to their opinion on how a person skilled in the art would consider the matter.

The opinions of such experts are meant for matters of science or art, but, usually, such experts also give their opinions on infringement, novelty, obviousness and other grounds of invalidity. Even though such statements or conclusions on obviousness, novelty or infringement may also involve matters of law, it is not fatal to the admissibility of the expert opinion. Courts will focus more on the reasoning offered by the expert in the opinion. Expert opinions of the experts are not binding on the court.

6.6.8.3 Court-appointed scientific advisers

Section 115 of the Patents Act, 1970, empowers the court to appoint an independent scientific adviser to assist the court or to enquire and report upon any question of fact or opinion (but not involving a question of interpretation of the law). The Indian Patent Office maintains a roster of such scientific experts.203 Courts usually resort to these scientific experts to gain an independent assessment. These assessments are considered valuable in highly contested matters where the parties’ expert testimonies have offered widely disagreeing opinions. Like any other expert opinion, the opinion of a court-appointed scientific adviser is also not binding on the court.

As per Rule 103 of the Patents Rules, 2003, the Controller is to maintain a roll of scientific advisers, to be updated annually. The roll contains the names, addresses, specimen signatures and photographs of scientific advisers; their designations; and information regarding their educational qualifications, the disciplines of their specialization and their technical, practical and research experience.

A person must possess the following qualifications to be enrolled as a scientific adviser:

-

a degree in science, engineering or technology or equivalent;

-

at least 15 years of technical, practical or research experience; and

-

holds or has held a responsible post in a scientific or technical department of the central or state governments or in any organization.204

The law provides that the fee or remuneration for such scientific advisers be provided by the Parliament, by law, for this purpose. However, usually, the parties share the costs of independent scientific experts.

The recently notified draft of the High Court of Delhi Rules Governing Patent Suits, 2020, also proposes the maintenance of a panel of scientific advisers to assist the court.

6.6.8.4 Hot-tubbing procedure

The procedure of hot-tubbing, where multiple expert witnesses give their evidence concurrently – and which has its origin in Australian law – is also permissible in India and has recently been ordered in some cases.205 The procedure for recording expert evidence through a hot-tubbing protocol was specified in Micromax Informatics Ltd v. Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson.206 The Delhi High Court Rules have also been amended to incorporate this procedure,207 including its protocol.208

Though there has yet to be a patent infringement action concluded in which evidence has been given by the hot-tubbing procedure, hot-tubbing is expected to be applied more frequently in the future.

6.6.9 Alternative dispute resolution: pre- and post-litigation mediation

Under the Commercial Courts Act, 2015, parties are usually expected to explore pre-litigation mediation. If the plaintiff does not seek urgent relief, Section 12A of the Commercial Courts Act, 2015, mandates pre-litigation mediation.

Section 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure also recognizes courts’ inherent power to refer parties to arbitration, conciliation, mediation or other forms of alternative dispute resolution. A court can exercise this power at any stage if there exist elements of an acceptable settlement. The parties may also request such a referral themselves.

Almost all district courts and High Courts in India have mediation centers for pre- and post-litigation mediation. These mediation centers are usually attached to each of the High Courts or district courts and are managed by a fully functional secretariat. The mediators at these centers are trained professionals. It is also possible for parties to seek the appointment of an expert mediator with specialized technical learning, skills, experience and domain knowledge. Mediation proceedings have proved to be quite efficient in almost all parts of the country. Significant success has been generally observed in resolving IP rights disputes and, most recently, in the resolution of certain SEP-related disputes.209

Indian Evidence Act, 1872, §101.

Commercial Courts Act, 2015, §2(1)(c)(vii).

2019 (12) SCC 210.

2015 SCC Online Del. 8227.

Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Ltd v. Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp., (2015) 6 SCC 807.

Bajaj Auto v. TVS Motors, (2009) 9 SCC 797; Az Tech (India) v. Intex Technologies (India), SLP (C) 18892 of 2017, order dated Aug. 16, 2017.

F Hoffman-La Roche Ltd v. Cipla Ltd, 2009 (110) DRJ 452 (DB); Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. v. Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, 2015 SCC Online Del. 8227.

[1975] AC 396.

SM Dyechem Ltd v. Cadbury (India) Ltd, (2000) 5 SCC 573.

F Hoffman-La Roche, (110) DRJ, paras 53–55 (DB).

F Hoffman-La Roche, (110) DRJ, paras 53–55 (DB).

AIR 1965 Mad. 327.

National Research and Development Corp.’s, Bilcare v. Amartara Pvt. Ltd., 2007 (34) PTC 419 (Del).

Mariappan v. AR Safiuallah, 2008 (5) CTC 97.

2008 (37) PTC 71 (Del.) (SJ), aff’d, 159 (2009) DLT 243 (DB) (though there is no express discussion on the six-year rule).

F Hoffmann-La Roche, 159 DLT (DB).

F Hoffmann-La Roche, 159 DLT (DB).

AstraZeneca AB v. Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd, MANU/DE/1939/2020.

Novartis AG v. Cipla Ltd, 2015 SCC Online Del. 6430, para 88.

Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. v. Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, 2015 SCC Online Del. 8227.

Merck Sharp and Dohme, 2015 SCC Online Del.; see also Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. JD Joshi, CS (OS) 2303 of 2009; Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. D Shah, CS (OS) 679 of 2013.

CS (COMM) 1648 of 2016, order dated Jan. 4, 2017.

CS (COMM) 107 of 2017, order dated Feb. 16, 2017.

Merck Sharp and Dohme, 2015 SCC Online Del.

2017 SCC Online Del. 7393.

See Franz Xaver Humer v. New Yash Engineers, (1996) ILR 2 Del. 791.

In re Distribution of Essential Supplies and Services during Pandemic, Suo Motu Writ Petition (Civil) 3 of 2021, order dated April 30, 2021; Rakesh Malhotra v. Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi, WP (C) 3031 of 2020, order dated April 20, 2021.

Merck Sharp and Dohme, 2015 SCC Online Del. 8227.

E.g., Victoria Foods Private Limited v. Rajdhani Masala Co. & Anr., CS(COMM) 108 of 2021, order dated March 24, 2022; Sun Pharma Laboratories Ld. v. Interio International P. Ltd & Ors., CS(COMM) 184 of 2022, order dated March 28, 2022.

Saraswathy v. Viswanathan, 2002 (2) CTC 199.

E.g., Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ.) v. Intex Technologies (India) Ltd, CS (OS) 1045 of 2014, judgment and order dated March 13, 2015; Dolby International v. GDN Enterprises Pvt. Ltd, CS (COMM) 1425 of 2016, orders dated Oct. 27, 2016, and Nov. 23, 2016; Koninklijke Philips NV v. Vivo Mobile Communications Co. Ltd, CS (COMM) 383 of 2020; Koninklijke Philips NV v. Xiaomi Inc., CS (COMM) 502 of 2020.

CS (COMM) 1222 of 2018, order dated July 12, 2019.

Communication Components Antenna Inc. v. Ace Technologies Corp., SLP (C) 21938 of 2019, order dated Sep. 20, 2019.

Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson v. Mercury Electronics, 2015 (64) PTC 105 (DEL).

M Sivasamy v. Vestergaard Frandsen A/S, 2009 (113) DRJ 820 (DB); Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ.) v. Lava International Ltd, CS (OS) 764 of 2015, order dated March 1, 2016; Pfizer Inc v. Union Remedies Ltd, 2016 SCC Online Bom. 8599; Delhi High Court (Original Side) Rules 2018, ch. VII r. 17.

Interdigital Technology v. Xiaomi Corp., CS (COMM) 295 of 2019, order dated Oct. 9, 2020.

Monsanto Technology LLC v. Nuziveedu Seeds Ltd, (2019) 3 SCC 381.

2010 SCC Online Mad. 5031.

(2019) 3 SCC 381, paras 22–23.

State of Himachal Pradesh v. Jai Lal, (1999) 7 SCC 280.

Vringo Infrastructure Inc. v. ZTE Corp., FAO (OS) 369 of 2014, order dated Aug. 13, 2014.

Vringo Infrastructure, FAO (OS) at para. 11.

F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd Cipla Ltd, MIPR 2016 (1) 1.

E.g., Micromax Informatics Ltd v. Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson, MANU/DE/1477/2019; Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ.) v. Intex Technologies (India) Ltd, CS (COMM) 769 of 2016, order dated Jan. 30, 2019.

MANU/DE/1477/2019.

Delhi High Court (Original Side) Rules 2018, ch. XI r. 6.

Delhi High Court (Original Side) Rules 2018, annex G.

Justice Prathiba M. Singh, “Samadhan-Mediation in Delhi” in National Conference on Mediation and Information Technology (High Court of Gujarat ed., 2022). “In Intellectual property rights (“IPR”) disputes however, the average percentage of settlements arrived at is a whopping 84.50%…Notably, 2017 was a rare year for the [Delhi High Court Mediation and Conciliation] Centre which saw 100% of all IPR matters referred, being settled. Even thereafter the percentages of settlement in IPR matters are hovering around 85% to 95% in the pre-pandemic years. Compared to IPR matters, the percentage of commercial disputes that are settled is comparatively lesser…”