Chapter 6 India

Authors: Justice Madan B. Lokur (ret.), Justice Gautam Patel, Justice Prathiba M. Singh and Justice Manmohan Singh (ret.)

6.1 Overview of the patent system

6.1.1 Evolution of the patent system

Intellectual property (IP) rights are governed by national law, which for members of the World Trade Organization (WTO), shall be in conformity with the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement).1 The TRIPS Agreement sets out the objective of IP rights in Article 7:

The protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights should contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare, and to a balance of rights and obligations.

As a member-nation of the WTO, India was required to amend or enact laws to conform to the TRIPS Agreement. However, this was a challenge for India. A significant reason was that, unlike many other countries, such as the United States of America (U.S.), where the Constitution recognizes the promotion and progress of science and arts and secures exclusivity granted to authors and inventors, the Constitution of India only encourages Indian citizens to have a scientific temper and prescribes a duty to develop the spirit of inquiry and reform.2 The Constitution of India mandates that no one shall be deprived of “property” except with the authority of law.3 Since patents are “property,” there is a positive constitutional entitlement to the grant and recognition of patents. The non-enforceable – but critical – chapter of the “Directive Principles of State Policy” in the Constitution of India further directs the Government to ensure the promotion of public health,4 the reduction of inequalities5 and the securing of systems that ensure ownership and control of resources for the common good.6 The basis and limitations for IP rights are, therefore, the right to property, the directive principles of state policy and the fundamental duties of citizens, apart from the various laws enacted periodically.

The journey of the Indian patent regime is reflected in three different periods: colonization, post-independence and globalization.7

Colonization. India inherited its patent regime from the British rule. When the British colonization of India ended, the Indian Patents and Designs Act, 1911, was in force and had created a system of patent administration in India under an administrative office – the Controller of Patents and Designs.

Post-independence. India enacted its first independent patent law in 1970. It came in the backdrop of two committees constituted to make recommendations: the Bakshi Tekchand Committee in 1949 and, later, the Justice Rajagopal Ayyangar Committee. Focusing on the special socioeconomic conditions in India, the recommendations of these two committees resulted in far-reaching changes in patent laws. Some of the significant changes introduced were with respect to food and drug patents, compulsory licensing, and connected working requirements. The law enacted in 1970 is credited with the growth of various industries, including the pharmaceutical industry, which, in two decades, gave India the distinction of being called “the pharmacy of the world” as Indian drug companies began exporting reasonably priced medicines to many countries.

Globalization. In 1991, India liberalized its economy and adhered to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT 1947), which was succeeded by the WTO, resulting in amendments being introduced in line with the TRIPS Agreement. These amendments saw India bring about fundamental changes permitting product patents in food, medicines and agrochemicals. The flexibilities in the TRIPS Agreement were used to maintain a balance: ensuring that the amendments would be gradually made systemic rather than forcing the closure of already-functioning industries. Statutory provisions relating to chemical and drug patents, patentability and other aspects of the amendments were tested repeatedly in the courts and were upheld as being within the Constitutional scheme while being fully compliant with the TRIPS Agreement. The judgment of the Supreme Court in Novartis v. Union of India8 recognized the need to curb the “evergreening” of patents while acknowledging the need to grant patent protection to incremental innovations. After Novartis, Indian courts have granted interim injunctions to protect patentees’ rights in pharmaceutical9 and agrochemical inventions.10 The courts have also protected claims to standard-essential patents (SEPs) by granting interim injunctions to secure the patentee’s right to royalties even pending trial.11 Courts have granted permanent injunctions12 and damages (in quite significant amounts)13 in cases of patent infringement and have also denied interim injunctions in appropriate cases.14 Each case has been decided on its own facts on the basis of settled legal principles. A current review of decisions would show no pro- or anti-patentee bias in the adjudication of patent cases.

6.1.2 The Justice N Rajagopala Ayyangar Committee Report

In 1957, the Government of India appointed a committee led by a distinguished retired Justice of the Supreme Court of India, Justice N Rajagopala Ayyangar, to examine the revision of the Patents Act and advise the Government in this respect.

The Justice N Rajagopala Ayyangar Committee report stated, in no uncertain terms, that the patent system was a quid pro quo system: the monopoly that a patentee obtains is only in exchange for the disclosure of the invention to the public, free to be used after the monopoly period is over. The quid pro quo, according to the report, also included the obligation on the part of the patentee to work the invention in India. The report also underscored, rather emphatically, that the patent system had failed in India because it had failed to spark the kind of innovation that it sought to encourage – underdeveloped countries could not yield the same result from the patent system as their more developed counterparts could. The patent system was recommended to be continued only because there was no better alternative to achieve better results – in their form at the time, patents were the lesser evil. The report was unequivocal in its apprehension that foreign patentees could misuse the patent system to capture large markets in India at the cost of domestic innovation while simultaneously not investing in the manufacture of the patented product.

The committee’s recommendations were a catalyst for wide changes in Indian patent law, eventually leading to the Patents Act of 1970, replacing the Indian Patents and Designs Act, 1911. The Patents Bill was introduced in 1965 and amended in 1967. The Patents Act, 1970, and Patents Rules, 1972 came into force on April 20, 1972.

6.1.3 The Patents Act, 1970 (pre–TRIPS Agreement)

The Patents Act, 1970, incorporated major provisions to reduce the social costs of foreign-owned patents. It prohibited patents on products useful as medicines and food, shortened the term of chemical process patents, and significantly expanded the availability of compulsory licensing. This spawned a powerful Indian pharmaceutical generic drugs industry.

In Bishwanath Prasad Radhey Shyam v. HM Industries,15 deciding an appeal in a case for infringement of a patent called “Means for Holding Utensils for Turning Purposes,” the Supreme Court said:

The object of the patent law is to encourage scientific research, new technology and industrial progress. Grant of exclusive privilege to own, use or sell the method or the product patented for the limited period, stimulates new inventions of commercial utility. The price of the grant of the monopoly is the disclosure of the invention at the Patent Office, which after the expiry of the fixed period of the monopoly passes into public domain.

The salient features of the Act (as enacted) were:

-

the reduction of the term of patent from 16 to 14 years;

-

a maximum of seven years for the term of a patent for the processes for drugs and foods;

-

no product patents available for food, drugs and medicines, including the products produced or obtained by chemical processes;

-

provisions prescribing nonworking as a ground for the grant of compulsory licenses, licenses of right and the revocation of patents;

-

the empowerment of government to use inventions for its own use;

-

provisions for the use of inventions for government purposes, research or instruction to pupils;

-

the endorsement of a “license of right” to patents related to drugs, foods and products of chemical reactions;

-

the codification of certain inventions as non-patentable;

-

the expansion of the grounds for opposition to the grant of a patent;

-

exemption from anticipation in respect of certain categories of prior publication, prior communication and prior use;

-

provisions for the secrecy of inventions relevant for defense purposes;

-

the mandatory furnishing of information regarding foreign applications;

-

the prevention of abuse of patent rights by voiding restrictive conditions in license agreements and contracts;

-

a provision for appeal to the High Court from decisions of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (“the Controller”); and

-

the separation of industrial designs from the law of patents.

However, many provisions changed after the TRIPS Agreement, as discussed in Sections 6.1.4.4.3 to 6.1.4.4.5.

6.1.4 International obligations and commitments

India is a member of the WTO, which came into being on January 1, 1995. The WTO administers the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT),16 which is an international agreement among countries to promote free international trade in goods. The WTO is a package deal in that its members must abide by the GATT agreement and a series of other international agreements. One such agreement is the TRIPS Agreement. India is also a member of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property,17 the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT),18 as well as the Budapest Treaty on the International Recognition of the Deposit of Microorganisms for the Purposes of Patent Procedure.

6.1.4.1 The TRIPS Agreement

TRIPS is one of the most comprehensive multilateral agreements on intellectual property rights.

Section 5 of TRIPS deals with patents. Article 27(1) of TRIPS provides that patents will be available for products or processes of inventions in all fields of technology, provided they are new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application. This was a departure from what the Patents Act, 1970 allowed at the time since no patents were allowed for “substances intended for use, or capable of being used, as food or as medicine or as drug.”19 In such cases, only method or process patents were allowed for such substances.

Article 70(8)–(9) of the TRIPS Agreement stipulates that, during the transition period, a country should provide a mechanism for patent protection for pharmaceutical and agricultural chemical products, including the grant of exclusive marketing rights (EMRs). On July 2, 1995, the U.S. alleged that India had not complied with these provisions. It requested the WTO for dispute consultations. A panel to hear the dispute issued a report on September 5, 1997, finding that India was indeed in violation of these TRIPS Agreement provisions.20 India’s appeal also failed. The appellate body found that, as on January 1, 1995, India was required to have a legal mechanism for patent protection as provided under Article 70(8)–(9) of the TRIPS Agreement.21

In 1997, the European Community requested another dispute consultation on similar grounds. The panel set up in this regard also ruled against India.22 Accordingly, in 1999, India introduced an amendment to comply with these requirements. These, and other amendments of 2002 and 2005, are discussed in Sections 6.1.4.4.3 to 6.1.4.4.5.

6.1.4.2 The Doha Declaration

Prior to the adoption of the TRIPS Agreement, most countries did not grant patents for medicines. This helped keep costs affordable and ensured access to medicines. The introduction of product patents for medicines under the TRIPS agreement was a matter of concern for developing countries and least-developed countries. Increasing the number of product patents for medicines implied that the cost of medications would increase and thwart access to medication.

The TRIPS Agreement required, among other things, that all WTO members introduce product and process patents in all fields of technology. Exceptions in fields related to the fulfillment of basic needs, such as in health, were not recognized or permitted.

In 2001, WTO members adopted a declaration at the WTO Ministerial Conference in Doha, Qatar, stating that it was important to interpret the TRIPS Agreement to support public health by promoting access to medicine and the creation of medicines.23 This was important for developing economies, including India, which had stressed the need to expand public health coverage at low and affordable costs. The Doha Declaration agreed that the TRIPS Agreement did not and should not prevent WTO members from taking measures to protect public health.24

The Doha Declaration recognized that the TRIPS Agreement should be interpreted and implemented in a manner conducive to its members, deploying the flexibilities built into the TRIPS Agreement.25 Consequently, each WTO member was free to determine the grounds on which compulsory licenses were to be granted and what constituted a national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency for invoking compulsory licensing provisions.26 The Doha Declaration also recognized that many countries had little or no manufacturing capacity in the pharmaceutical sector and might face difficulties in the effective use of the TRIPS Agreement’s compulsory licensing provisions.27 Pursuant to this, an amendment was accepted in Article 31bis of the TRIPS Agreement, permitting countries to grant compulsory licenses even for export to other countries with insufficient or no manufacturing capacity.

The Doha Declaration also clarified flexibilities for members to adopt an international principle of exhaustion of rights28 in accordance with Article 6 of the TRIPS Agreement.29 The principle of exhaustion means that, once patent holders sell a patented product, they cannot prohibit the subsequent resale of that product, since their rights in respect of that product have been “exhausted” by the act of selling the product. The Doha Declaration reaffirmed that members were free to establish their own regime for such exhaustion to ensure that patent rights did not impede legitimate products entering global supply chains.

6.1.4.3 The Patent Cooperation Treaty

The PCT provides a platform to facilitate the filing of a single international patent application to seek protection across PCT contracting states. This is beneficial for an applicant because, in the traditional system, separate applications for patents had to be made in each jurisdiction across the world. The international search reports and written reports generated by the International Searching Authorities as well as International Preliminary Reports on Patentability (Chapter II) drawn by the International Preliminary Examining Authorities assist the applicant in deciding whether to proceed with the national phase and, if so, in which countries, based on the likelihood of success as per the search report. The PCT system has also resulted in a considerable reduction in costs for applicants.

6.1.4.4 Amendments and implementation in India

6.1.4.4.1 Patent Cooperation Treaty implementation in India

India signed and acceded to the PCT in September 1998, which entered into force in India in December 1998. The provisions relating to applications under the PCT were incorporated under the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002. Under the Patents Act, 1970, an “international application” was defined as an application made as per the provisions of the PCT.30 Four offices in India (New Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai and Mumbai) and the International Bureau in Geneva, Switzerland were designated as receiving offices for international applications. Section 7 of Act prescribes the form in which an applicant makes an application for its invention and also provides for making a simultaneous application under both the PCT and the Act if a corresponding application has been filed before the Controller in India.31

Chapter III of the Patents Rules, 2003, contains the provisions for filing an international application, the form in which an application is to be made, fees payable to the examining authority, time limits for establishing an international search report and other related rules for applications under the PCT. The term of a patent granted in India for a PCT international application is 20 years from the date of its filing under the PCT.32

6.1.4.4.2 Patent prosecution highway

Apart from the PCT system, several countries and regions have recently created “patent prosecution highways” which provide for accelerated examination, the sharing of search reports and so on, which result in the speedier examination and grant of patents. Such prosecution highways can either be bilateral or multilateral. In India, the first patent prosecution highway was initiated in 2019 by the Indian Patent Office as a bilateral pilot patent prosecution highway program with the Japan Patent Office. Guidelines for the same were published, though the pilot is limited to 100 cases per year, on a first-come-first-served basis. Depending on the evaluation of this pilot highway, long-term patent prosecution highways with one or more patent offices across the country may be a reality.

6.1.4.4.3 The 1999 amendment, post–TRIPS Agreement

Upon coming into effect on January 1, 1995, the TRIPS Agreement provided for transitional periods for WTO members to introduce legislation complying with the obligations under the agreement. India has been a WTO member since January 1995.

For developing countries like India, the deadline for complying with the TRIPS Agreement was the year 2000. Article 65(4) of the TRIPS Agreement provided a special transitional provision for those countries that did not grant product patents. As per this provision, an additional period of five years (i.e., until 2005) on the initial TRIPS Agreement transitional period was permitted for introducing product patent protection.

India needed to provide a means for filing patent applications during the transitional period. The “mailbox provision” allowed applicants to file for patents, thereby establishing filing dates, while at the same time permitting members to defer the granting of product patents. In addition, India also needed to provide EMRs in exchange for permission to delay the grant of product patents until January 1, 2005.

Transitional arrangements were introduced through Section 2 of the Patents (Amendment) Act, 1999, through the insertion of Section 5(2) of the Patents Act, 1970, allowing product patent applications to be filed through a “mailbox,” while Chapter IVA provided for the grant of EMRs if certain conditions were fulfilled

EMRs were introduced as a transitory provision to help developing countries that followed a process patent regime to slowly phase into a product patent regime. In order to bring in transitional measures for the recognition of the TRIPS Agreement obligations, the Patents (Amendment) Act, 1999, introduced a system for the grant of EMRs. This allowed inventors to file early applications for the grant of patents and to establish filing dates so that, when patent protection was ultimately granted, these applications would be considered on the basis of the date of filing or priority dates. These provisions were considered necessary under the TRIPS Agreement,33 pending the initiation of a streamlined process in India for granting product patents relating to drugs, pharmaceutical and agricultural chemical products.

EMRs are applicable where a patent is granted for the same product in another WTO member after 1995 (the date of entry into force of the TRIPS Agreement), provided marketing approval for the product was obtained in such other WTO member. However, EMRs are limited only to pharmaceutical and agricultural chemical products. From a simple dictionary definition of the term, the meaning of “exclusive marketing rights” appears to be very similar to that of patent rights; however, in theory, EMRs prevent others from making or using patented products. The rights holder can indirectly prevent others from marketing products based on such use since they would lack the authorization to do so. Patent protection and EMRs are alternatives to each other and are not used concurrently.

EMRs under the 1999 amendment could only be granted for products intended for or capable of being used as a medicine or drug. For an applicant to have the exclusive right to sell or distribute the product in India, pending the grant or rejection of the application for the product patent, the following conditions needed to be fulfilled:

-

a patent and approval to sell the same invention applied for (on or after January 1, 1995) in another WTO member had been granted after the date of making an application for the product patent;34 or

-

a patent for the method, process or manufacture of the invention applied for (on or after January 1, 1995) and relating to the same product had been granted in India on or after the date of making an application for the product patent;35 and

-

approval to sell or distribute the product had been received from the Central Government.36

EMRs were granted for a period of five years from the date of such approval or until the grant or rejection of the application for the product patent, whichever was earlier.

As per the 1999 amendment, no application for the grant of a product patent could be referred by the Controller to an examiner for making a report until December 31, 2004.37 For the said 10-year period, the applications were kept in a “black box,” a figurative expression for applications pending examination. After this date, the application would be referred to an examiner for a report on whether the claimed invention was within the meaning under Section 3 of the Patents Act, 1970, or whether the invention was such for which no patent could be granted under Section 4 of the Act. If the necessary preconditions were not met, the application would be rejected.38 If the preconditions were fulfilled, the Controller could proceed to consider the application for the grant of a patent.39

The 1999 amendment also included provisions authorizing the Central Government – under expedient circumstances and keeping in mind the public interest at large – to sell or distribute the product by itself or through an authority so empowered in writing.40 Moreover, the Central Government also had the power to direct that the product be sold at a price determined by it after specifying its reasons and the public interest involved.

All suits relating to infringement under Section 24B of the Act would be dealt with in the same manner as suits concerning infringement of patents under Chapter XVIII.

In India, some EMRs were granted relating to medicinal products. Suits for infringement restraining violation of EMR rights were also instituted. However, all EMRs came to an end after the full-scale implementation of the amendments with effect from January 1, 2005. With the introduction of the 2005 amendments, all pending applications for the grant of EMRs were automatically considered as applications for product patents and dealt with accordingly.

6.1.4.4.4 The 2002 amendment, post–TRIPS Agreement

This 2002 amendment to the Patents Act, 1970, was introduced to (a) bring the patent regime in India in line with the TRIPS Agreement; (b) bring the law on patents in line with the increasing development of technological capability of India; (c) provide the necessary safeguards for the protection of public interest and national security; (d) harmonize the procedure for the grant of patents in accordance with the international practices; and (e) make the system more user-friendly.

Some of the salient features of the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002, were as follows:

-

The term of every patent granted after the commencement of the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002, was increased to 20 years from the date of filing of the application.41

-

The time for restoration of a lapsed patent was increased to 18 months.42

-

A new definition for “invention” was added: a patent could be for a process or product that was new, involved an inventive step or was capable of industrial application.43

-

A new definition for “inventive step” was added.44

-

The negative list of what were not considered inventions (i.e., non-patentable subject matter) was amended and expanded in light of Article 27(2)–(3) of the TRIPS Agreement.45

-

The concept of a request for the publication of a patent application was introduced.46

-

An onus-of-proof provision was introduced, requiring the defendant to prove that its process for obtaining the product in question was different from the patented process in cases where an identical final product was obtained from such a process.47

-

The chapter on compulsory licensing was substituted with provisions and procedures consistent with the TRIPS Agreement,48 and the provisions relating to the license of rights were omitted.49

-

The Bolar exemption was introduced.50

-

The parallel import of patented products was introduced.51

-

All appeals under the Act were redirected from the High Courts to a specialized tribunal (i.e., the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB)52 since abolished in 2021).53

-

National security provisions were amended.54

6.1.4.4.5 The 2005 amendment, post–TRIPS Agreement

The amendments of 2005 were introduced to bring Indian patent laws into further compliance with the TRIPS Agreement because the transitional period available to India was ending in 2005. Some of the salient features of the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005, were as follows:

-

The definition of “inventive step” was amended.55

-

The definition of “new invention” was added.56

-

The definition of “patent” was amended.57

-

The negative list of what were not considered inventions (i.e., non-patentable subject matter) was amended.58

-

The provisions that provided that only the process and not the product itself would be patented in cases of inventions relating to food, drugs and medicines were deleted.59 This ensured that product patent protection was available for all fields.

-

The chapter relating to EMRs was omitted,60 and the provisions relating to it were modified.

-

Two levels of opposition were introduced – pre-grant and post-grant. All grounds available for pre-grant opposition were also made available to interested parties for challenging a patent in post-grant opposition within one year from the date of publication of the grant of patent.61

-

Pursuant to the Doha Declaration, the grounds for seeking compulsory licensing were expanded by adding a provision for the issuance of compulsory licenses for the manufacture and export of patented pharmaceutical products to countries that had insufficient manufacturing capacity in the pharmaceutical sector if that country had allowed such importation by notification.62

-

Jurisdiction for trying revocation petitions to revoke granted patents was shifted from the High Courts to the IPAB with a view to extending its jurisdiction to the revocation of patents.63 This now stands reversed in 2021.64

-

Certain provisions were amended to bring the patent regime in India in line with the PCT, to which India is a signatory.65

6.1.5 Patent application trends

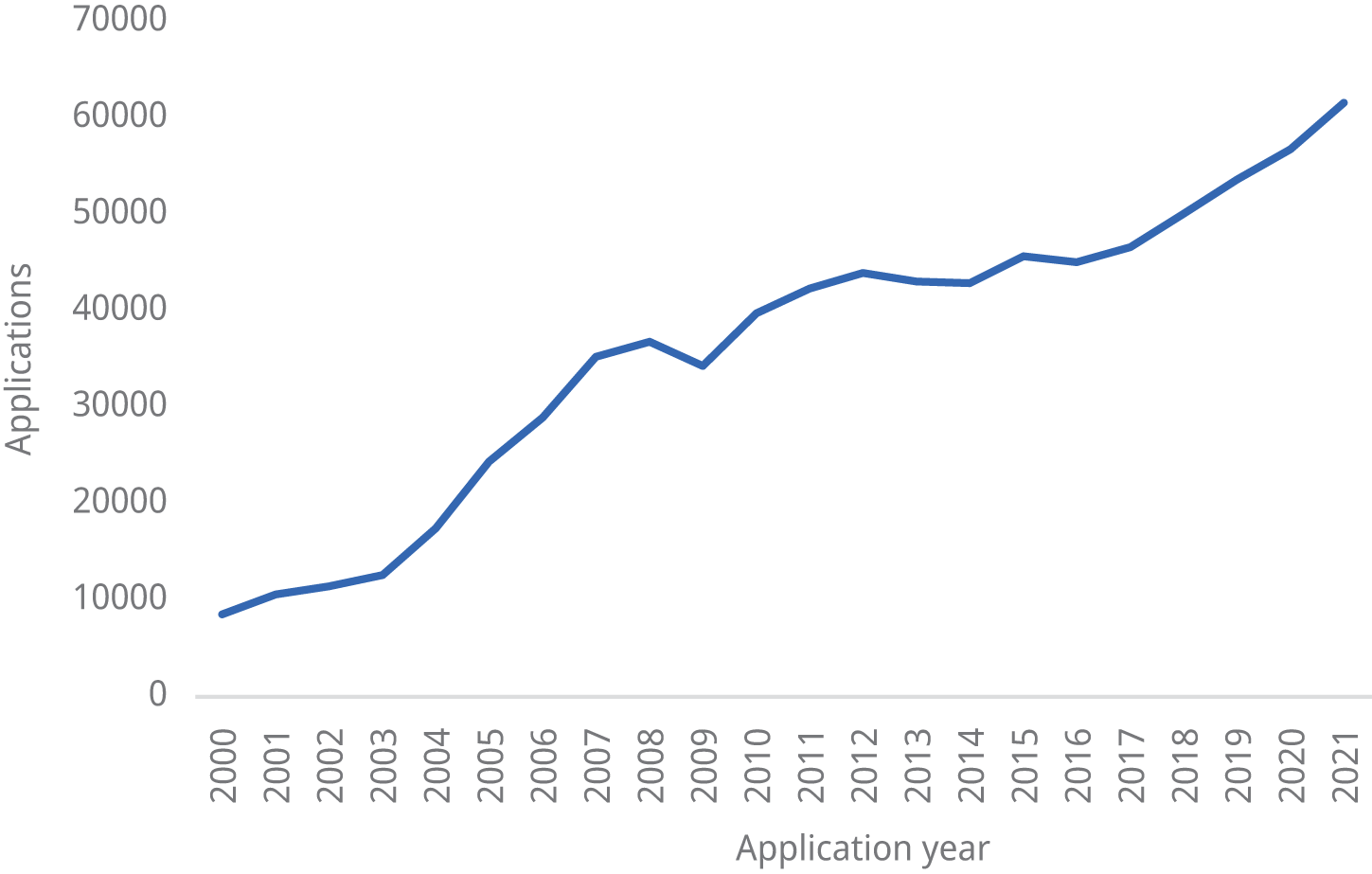

Figure 6.1 shows the total number of patent applications (direct and Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) national phase entry) filed in India from 2000 to 2021.

Figure 6.1 Patent applications filed in India, 2000–2021

Source: WIPO IP Statistics Data Center, available at www3.wipo.int/ipstats/index.htm?tab=patent

6.2 Patent institutions and administrative review proceedings

6.2.1 Patent institutions

6.2.1.1 Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks

The Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks is located in Mumbai. The Controller supervises the working of the Patents Act, 1970, the Designs Act, 2000, and the Trade Marks Act, 1999, and also renders advice to the Government on matters relating to these subjects.

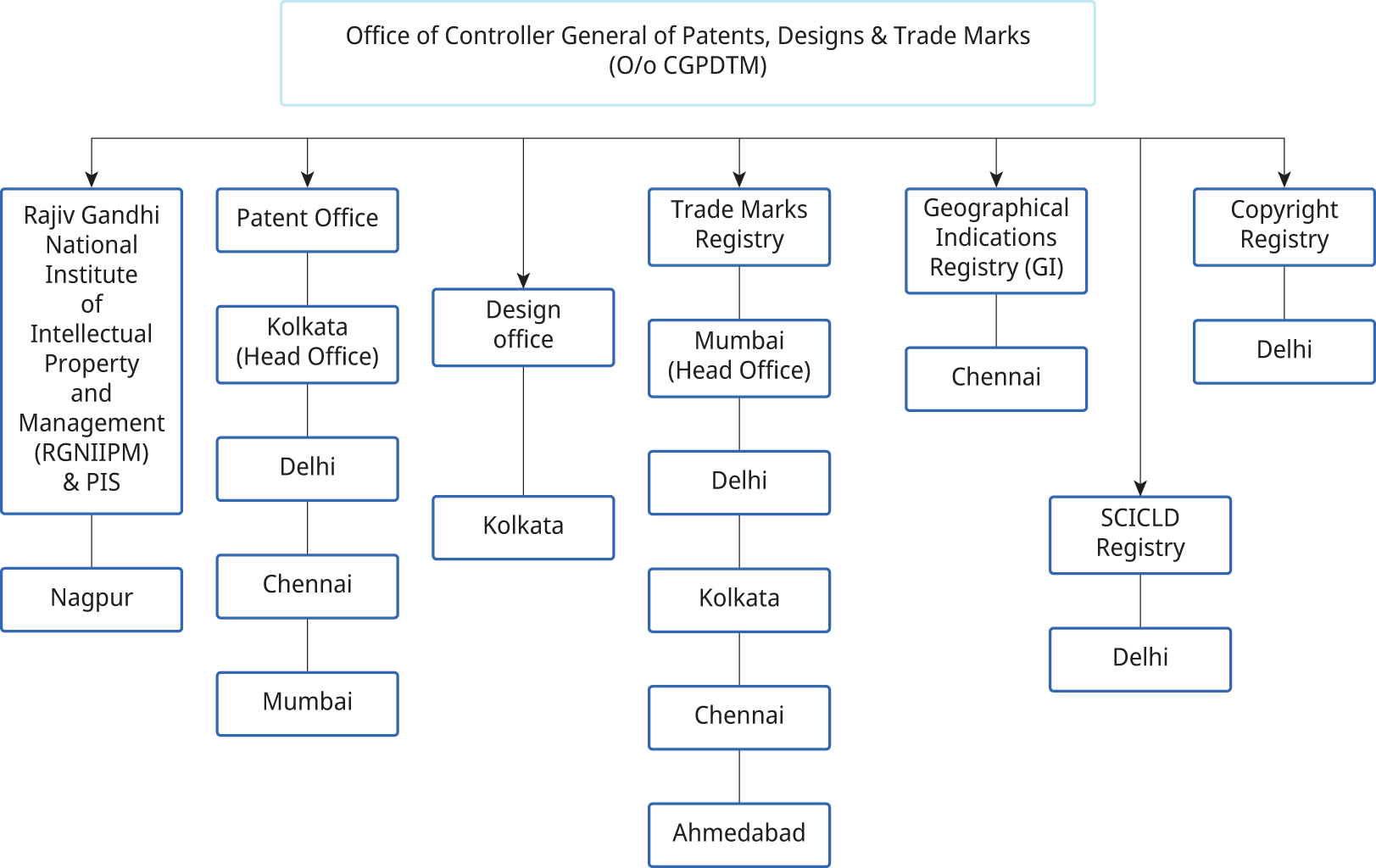

The Central Government may appoint as many examiners and other officers with such designations as it thinks fit.66 Minimum qualifications are prescribed. These officers function under the Controller’s superintendence. Higher qualifications are prescribed for the position of Senior Joint Controller of Patents and Designs. The organizational structure of the Office is shown in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2 Organizational structure of the Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks

Source: Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks, About Us, ipindia.gov.in/about-us.htm

6.2.1.2 The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade

The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade was established in 1995 and reconstituted in 2000 when it was merged with the Department of Industrial Development. The department’s purpose is to promote and accelerate the industrial development of the country by facilitating investment in new and upcoming technologies, foreign direct investment and supporting the balanced development of industries.

The department is the nodal department for all matters related to the protection of IP rights in the fields of patents, trademarks, copyrights, industrial designs and geographical indications.

6.2.1.3 National Institute of Intellectual Property Management, Nagpur

The National Institute of Intellectual Property Management is a national center for excellence in training, management, research and education in IP rights. The institute trains examiners of patents and designs, examiners of trademarks and geographical indications, IP professionals and IP managers in the country. The institute also facilitates research on IP-related issues.

The Patent Information System was established by the Indian Government in 1980 to maintain a comprehensive collection of patent specifications and patent-related literature worldwide. It is also located in Nagpur within the premises of the National Institute of Intellectual Property Management.

6.2.1.4 Cell for IPR Promotion and Management, constituted under the National Intellectual Property Rights Policy

The Cabinet of Ministers of the Central Government approved the National Intellectual Property Rights Policy on May 12, 2016.67 This policy drew a future roadmap for IP rights in India and made several recommendations. Following one of the recommendations of the 2016 policy, a specialized professional body – the Cell for IPR Promotion and Management – was created under the aegis of the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, and it has been instrumental in taking forward the objectives and visions of the policy. Since the adoption of the policy, the cell has worked toward changing the IP landscape of the country, which among other things, has included:

-

IP rights awareness programs, which are conducted in over 200 academic institutions for the industry, police, customs and the judiciary;

-

reaching out to rural areas – awareness programs are being conducted using satellite communication (EduSat). In one such program, 46 rural schools, with a combined total of 2,700 students, were reached. Over 300 schools and more than 12,000 students have been reached;

-

more focus on developing e-content and disseminating content through online channels;

-

including content on IP rights in the National Council of Educational Research and Training commerce curriculum. Work is ongoing to include IP rights in other academic streams; and

-

conducting competitions in conjunction with industry for school and college students to develop the “innovative spirit.” Some competitions have included the development of mobile applications, videos and online games.

As part of the awareness campaign, the Cell for IPR Promotion and Management also launched India’s first IP mascot – “IP Nani” – in collaboration with the European Union Intellectual Property Office. IP Nani is an animated grandmother who sends out messages for the protection and enforcement of IP. There are also a series of animated videos on IP rights for school students.68 These videos are available for viewing on platforms such as YouTube.69

6.2.1.5 The Department of Science and Technology – Patent Facilitation Programme

The Department of Science and Technology, under the Ministry of Science and Technology, has been implementing its Patent Facilitation Programme since 1995. It has established a Patent Facilitating Cell at the Technology, Information, Forecasting Assessment Council (an autonomous body of the department) and, subsequently, 26 patent information centers in various states. The patent facilitating cells and patent information centers create awareness of and extend assistance in protecting IP rights at the state level, including for patents, copyright, industrial designs, geographical indications and so on.

These patent information centers have also established IP cells in universities in their respective states to enlarge the network. Today, more than one hundred such cells have been created in different state universities. In addition, these centers are also mandated to provide assistance to inventors from government organizations and from central and state universities. They also render ongoing technical and financial assistance in filing, prosecuting and maintaining patents on behalf of the Government, research and development institutes, and academic institutions.70 The mandate of the program is:

-

providing patent information as a vital input to research and development;

-

facilitating patent and IP rights facilitation for academic institutions and Government research and development institutions;

-

providing IP rights policy input to the Government; and

-

conducting IP rights training and awareness programs in the country.

6.2.1.6 Traditional Knowledge Digital Library

The Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) is a pioneering initiative in India to protect Indian traditional medicinal knowledge and prevent its misappropriation. It was set up in 2001 as a collaboration between the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research and the Ministry of Ayush, Government of India. The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research is a contemporary research and development organization and a pioneer in India’s IP movement.

The TKDL has overcome the language and format barrier by systematically and scientifically converting and structuring the available contents of ancient texts on Indian systems of medicine (i.e., Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani, Sowa Rigpa and Yoga) into five international languages – English, Japanese, French, German and Spanish – with the help of information technology tools and an innovative classification system called the Traditional Knowledge Resource Classification. More than 360,000 formulations and practices have been transcribed into the TKDL database.

The classification has also structured and classified the Indian traditional medicine system into several thousand subgroups for Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha and Yoga. The Traditional Knowledge Resource Classification has enabled the incorporation of about 200 subgroups under International Patent Classification A61K 36/00, more than the few subgroups earlier available on medicinal plants under A61K 35/00, thus enhancing the quality of search and examination of prior art for patent applications in the area of traditional knowledge.

The TKDL has also established international specifications and standards for setting up traditional knowledge databases based on TKDL specifications. These standards were adopted in 2003 by the committee in the fifth session of the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Expression of Folklore.

Currently, the TKDL is based on open-source and open-domain texts of Indian systems of medicine. The TKDL acts as a bridge between these books (prior art) and patent examiners. Access to the TKDL is available to 13 patent offices under the TKDL Access (Non-disclosure) Agreement,71 which has inbuilt safeguards on nondisclosure to protect India’s interest against any possible misuse.

The TKDL is proving to be an effective deterrent against biopiracy and has been recognized internationally as a unique effort. It has set a benchmark in traditional-knowledge protection around the world, particularly in traditional-knowledge-rich countries, by demonstrating the advantages of proactive action and the power of strong deterrence. The key here is preventing the grant of incorrect patents conferring monopolies on aspects of traditional knowledge, by ensuring access to prior art relating to traditional knowledge for patent examiners without restricting the use of that traditional knowledge.

6.2.2 Administrative review proceedings

6.2.2.1 Intellectual Property Appellate Board

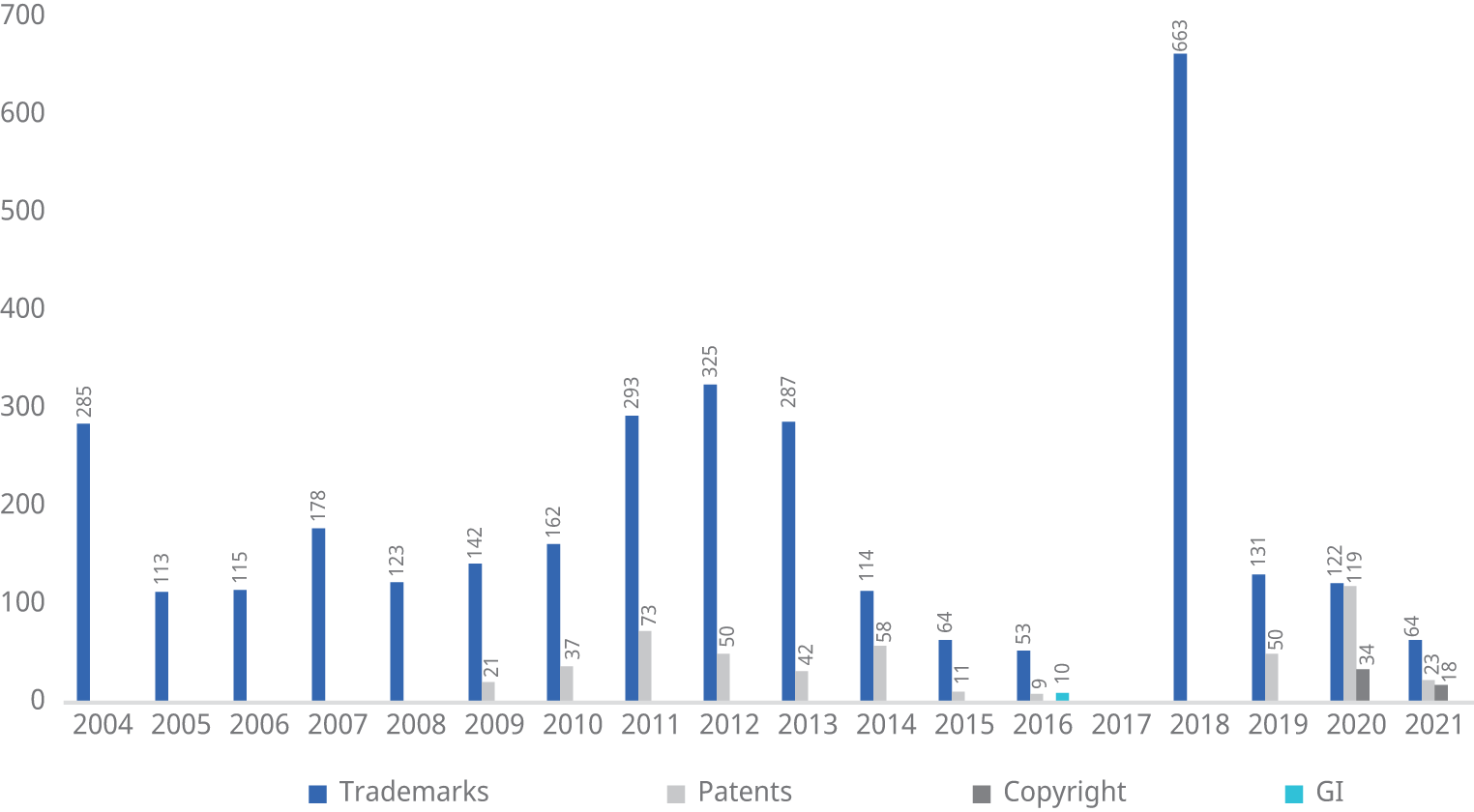

Under the Patents Act, 1970, the appellate jurisdiction to hear appeals and the original jurisdiction to revoke patents was conferred on the High Courts in India. Both these jurisdictions were redirected to the IPAB as a specialized IP tribunal in 2002 and 2005. This was to enable the speedy disposal of such matters (see Figure 6.3 regarding the disposal of cases by the IPAB).72 However, in 2021, the Central Government was of the view that this stated objective of speedy disposal was not being achieved and abolished the IPAB, redirecting such matters back to the High Courts.73

Figure 6.3 Disposal of cases at the Intellectual Property Appellate Board, up to February 13, 2021

Note: GI = geographical indication.

Source: Jacob Schindler, Top Judge’s Blueprint for the Future in IP Litigation in India, IAM Media (May 5, 2021), www.iam-media.com/law-policy/specialised-ip-bench-in-india-long-overdue-says-delhi-high-court-veteran

6.2.2.2 Pre-grant opposition

The scheme of pre-grant oppositions was streamlined by the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005. Prior to this, a pre-grant opposition could only be filed by a “person interested.” The amendment now allows any person to file a pre-grant opposition. It can be filed when an application for a patent has been published, but the patent has not yet been granted under Section 25(1) of the Patents Act, 1970. There is no time limit within which a pre-grant opposition must be filed after publication.

6.2.2.2.1 Procedure of pre-grant opposition

The pre-grant opposition procedure broadly follows these steps:

- 1. The pre-grant opposition is filed, along with evidence, if any.74

- 2. The Controller forms a prima facie opinion on the pre-grant opposition filed. They decide either to issue notice of the opposition to the patent applicant or to reject the opposition prima facie without issuing notice to the patent applicant.75

- 3. If notice has been issued, the patent applicant may reply (along with evidence, if any) within three months from the date of the notice by the Controller.76

- 4. The Controller may hold a “hearing.” This is followed by a decision, ordinarily within one month.77 The Controller is required to either reject or grant the patent.

6.2.2.2.2 Grounds on which pre-grant opposition can be filed

Section 25(1) of the Patents Act, 1970, provides a list of grounds on which a pre-grant opposition can be filed. The list is exhaustive:

- (a) that the applicant for the patent or the person under or through whom he claims, wrongfully [emphasis added] obtained the invention or any part thereof from him or from a person under or through whom he claims;

-

(b) that the invention so far as claimed in any claim of the complete specification has been published before the priority date of the claim –

- (i) in any specification filed in pursuance of an application for a patent made in India on or after the 1st day of January, 1912; or

-

(ii) in India or elsewhere, in any other document:

Provided that the ground specified in sub-clause (ii) shall not be available where such publication does not constitute an anticipation of the invention by virtue of sub-section (2) or subsection (3) of section 29;

- (c) that the invention so far as claimed in any claim of the complete specification is claimed in a claim of a complete specification published on or after priority date of the applicant’s claim and filed in pursuance of an application for a patent in India, being a claim of which the priority date is earlier than that of the applicant’s claim;

-

(d) that the invention so far as claimed in any claim of the complete specification was publicly known or publicly used in India before the priority date of that claim.

Explanation. – For the purposes of this clause, an invention relating to a process for which a patent is claimed shall be deemed to have been publicly known or publicly used in India before the priority date of the claim if a product made by that process had already been imported into India before that date except where such importation has been for the purpose of reasonable trial or experiment only;

- (e) that the invention so far as claimed in any claim of the complete specification is obvious and clearly does not involve any inventive step, having regard to the matter published as mentioned in clause (b) or having regard to what was used in India before the priority date of the applicant’s claim;

- (f) that the subject of any claim of the complete specification is not an invention within the meaning of this Act, or is not patentable under this Act;

- (g) that the complete specification does not sufficiently and clearly describe the invention or the method by which it is to be performed;

- (h) that the applicant has failed to disclose to the Controller the information required by section 8 or has furnished the information which in any material particular was false to his knowledge;

- (i) that in the case of a convention application, the application was not made within twelve months from the date of the first application for protection for the invention made in a convention country by the applicant or a person from whom he derives title;

- (j) that the complete specification does not disclose or wrongly mentions the source or geographical origin of biological material used for the invention;

- (k) that the invention so far as claimed in any claim of the complete specification is anticipated having regard to the knowledge, oral or otherwise, available within any local or indigenous community in India or elsewhere, but on no other ground, and the Controller shall, if requested by such person for being heard, hear him and dispose of such representation in such manner and within such period as may be prescribed.

6.2.2.2.3 Locus standi to file pre-grant oppositions

Under Section 25(1) of the Patents Act, 1970, “any” person can file a pre-grant opposition. A pre-grant opposition is deemed to be an extension of the examination by the Patent Office, and, thus, the standing requirement is diluted. Nevertheless, precedents demonstrate that courts come down heavily against fake pre-grant oppositions or those filed by impostors solely to harass or to delay the grant rather than with any genuine intent to remove invalid patents.78

6.2.2.3 Post-grant opposition

A post-grant opposition can be filed under Section 25(2) of the Patents Act, 1970, by a “person interested” after the grant of patent but within one year from the date of publication of the grant of a patent.

6.2.2.3.1 Procedure in filing post-grant opposition

The post-grant opposition procedure broadly follows these steps:

- 1. A post-grant opposition is filed, along with evidence, if any.79 A copy must be supplied to the patentee.80

- 2. The Controller constitutes an opposition board of three examiners (other than the examiner who examined the patent).81

- 3. The patent applicant may reply to the opposition, providing evidence, if any, within two months.82 If no reply is filed, the patent is deemed to be abandoned.83 The Controller also notifies the patentee.84 The time for this reply begins from the date the patent applicant is served with the opposition by the opponent.

- 4. The opponent then has one month to respond to the patent applicant’s reply statement.85

- 5. The opposition board prepares a report with reasons on each ground taken in the notice of opposition. The report contains the board’s joint recommendation and is made within three months of the date on which the documents were forwarded to the board.86

- 6. The Controller schedules a hearing. This is followed by a decision.87 At the hearing, the Controller may require members of the opposition board to be present. If either of the parties wishes to be heard, this is permitted on payment of a fee and after notice. If no notice to attend the hearing is received from either party, the Controller can decide the opposition without a hearing. The order must be reasoned. The recommendation of the opposition board is not binding, though it is of persuasive value. Thus, the board’s recommendation should not be lightly ignored without stated reasons.

A party can also file new documents before the scheduling of the hearing, provided prior leave of the Controller is obtained.88 Further, a party can rely upon “any publication” that may not have been filed earlier, provided that there has been five days’ notice and that the details of the publication are given to the other party.89

In Cipla Ltd v. Union of India, the Supreme Court held that it would be mandatory to issue a copy of the recommendation of the Opposition Board to the parties, so that the principles of natural justice are duly adhered to.90

6.2.2.3.2 Grounds on which post-grant opposition can be filed

The grounds for post-grant opposition are the same as those for pre-grant opposition. The grounds are exhaustive.

6.2.2.3.3 Locus standi to file post-grant oppositions

Section 2(1)(t) of the Patents Act, 1970, defines “person interested” in an inclusive manner to include a person engaged in or promoting research in the same field as that to which the invention relates. Precedents have interpreted the term “person interested” broadly to cover any person who has a direct, present and tangible interest in the patent and those whose interests are adversely affected because of the patent.91 The term has been construed to include even nongovernmental organizations that have an interest or stake in the existence or invalidity of the patent – commercial interest is not a necessary condition.92

6.2.2.3.4 Appeals from pre-grant and post-grant oppositions

An appeal lies to the jurisdictionally competent High Court from an order of rejection of a patent application in a pre-grant opposition and from an order revoking or maintaining the grant of patent in a post-grant opposition. No appeal lies from the grant of a patent in a pre-grant opposition.93

6.3 Judicial institutions

6.3.1 Court system in India

6.3.1.1 Hierarchy of courts

There is a common court structure across India, with the Supreme Court of India at its apex. The Supreme Court of India is a court established under the Constitution of India. It is located in New Delhi and is the final appellate authority in the Indian judicial system. The Supreme Court has appellate, constitutional, review and special jurisdictions. It also has limited original jurisdiction for constitutional matters, though not for IP matters.

Below the Supreme Court of India are the various High Courts of India. The Supreme Court exercises appellate jurisdiction over High Court decisions. However, all High Courts and the Supreme Court of India occupy equal constitutional status. While, typically, each federal Indian state has a designated High Court, some states share a High Court. There are 24 High Courts in India.

All High Courts have appellate, constitutional and review jurisdiction. A few High Courts also have “original” jurisdiction – civil cases, including IP suits, can be directly filed in these High Courts, subject to a certain minimum pecuniary value that may vary from one state to another. Such High Courts are those of Delhi, Bombay (Mumbai), Madras (Chennai), Calcutta (Kolkata) and Himachal Pradesh (Shimla). All appeals from a High Court lie to the Supreme Court, though some High Courts also possess an intracourt appeal system from a single judge of the High Court to a bench comprising two judges (i.e., division bench).94

Each federal Indian state is typically divided into several districts. Below the High Courts of each state are the district and sessions courts for each such district. The district court is for civil matters, and the sessions court is for criminal matters. Below these courts are the courts of sub-judges for civil matters and the magistrates’ courts for criminal matters.

6.3.1.2 Commercial courts

The Commercial Courts Act, 2015, was enacted to provide fast-track courts for the resolution of certain commercial disputes, which includes IP rights disputes. All commercial disputes beyond a certain minimum specified value must be filed under the fast-track system of the Commercial Courts Act, 2015. Each district now has designated commercial courts for such disputes. Each High Court having original jurisdiction also has a Commercial division to hear such fast-tracked commercial disputes. Further, every High Court has a Commercial Appellate division to hear appeals for fast-tracked commercial disputes.

6.3.1.3 Appointment and tenure of judges

Judges of the High Courts and the Supreme Court of India are selected by a committee (called “the Collegium”) consisting of the three or five seniormost judges of the Supreme Court and headed by the Chief Justice. The executive can give its views on specific candidates, though the Collegium has the final say. A High Court judge could be from the district judiciary95 (or a practicing advocate with a minimum of 10 years’ practice).

Appointments to the subordinate judiciary (i.e., lower than the district court: the Provincial Civil Service–Judicial) are made by either the state public service commissions or the High Court concerned. The selection process involves written tests and an interview. Selected candidates are appointed as judges in the subordinate judiciary as sub-judges. High Courts also conduct the selection process for the Higher Judicial Service’s appointment of district judges. Candidates for the Higher Judicial Service are sub-judges and advocates with a minimum of seven years’ practice.

6.3.2 Judicial education on intellectual property

The National Judicial Academy (NJA) is a training institute located in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, established and fully funded by the Government of India. The NJA is an independent society established in 1993 under the Societies Registration Act, 1860. The Honorable Chief Justice of India is the Chairman of the General Body of the NJA and the Chairman of the Governing Council, the Executive Committee and the Academic Council of the NJA.

The NJA’s academic programs are guided by the National Judicial Education Strategy, launched in 2007. Under this strategy, the NJA has established a national system for judicial education. The NJA conducts a vibrant training program for judges at all levels throughout the year. The program is addressed by speakers who may be lawyers or people with specialized knowledge, including economists and foreign experts.

As a joint initiative of the World Intellectual Property Organization and the NJA, seminars, talks and so on are organized by the NJA for the benefit of lawyers, academics and students.

6.4 Challenges to patents

Under Section 13(4) of the Patents Act, 1970, the grant of a patent does not guarantee its validity.96 The underlying principle is that allowing an invalid patent to continue on the register is against the public interest, so every opportunity is provided to remove invalid patents. There are various levels of challenges provided in the Act against a patent application or a granted patent. Such challenges can be made either prior to or after the grant:

-

Pre-grant opposition under Section 25(1);

-

Post-grant opposition under Section 25(2) before the Patent Office, introduced in 2005;

-

revocation under Section 64(1) before the High Court;97 and

-

a counterclaim seeking revocation in a suit for infringement under Section 64(1), in which case the infringement suit and the counterclaim are both transferred to the relevant High Court.98

Other challenges to patents or the exercisable rights are compulsory licenses and government use (under Sections 84, 92, 102 and others) and revocation (under Section 66).

There has been significant discontent – especially after the 2002 and 2005 amendments – about the multitude of challenge avenues. These provisions for patent challenges may appear to encourage abuse by patent opponents and result in patent grants being held up or delayed almost indefinitely. These apprehensions have been assuaged to a large extent by judicial precedents, which have streamlined the filing of oppositions and dealt with challenges to orders passed in oppositions. In UCB Farchim v. Cipla Ltd,99 the Delhi High Court confirmed that, once a pre-grant opposition is dismissed and the patent is granted, the order granting the patent cannot be challenged by way of an appeal. The only remedy available is to file a post-grant opposition or a revocation. In Snehlata C Gupte v. Union of India,100 the practice of filing serial oppositions to hold up the grant of a patent was stopped by the Delhi High Court. The court issued a series of directions preventing delays in patent grants. In Aloys Wobben v. Yogesh Mehra,101 the Supreme Court categorically held that one person cannot pursue both a revocation application and a counterclaim seeking revocation. These and other decisions have ensured that duplicity and parallel proceedings are avoided to the extent possible.

6.5 Patent infringement

The ability to enforce patents is a crucial right for any patentee. Chapter XVIII of the Patents Act, 1970, addresses infringement, forums, remedies, defenses and counterclaims.

6.5.1 Claim construction

Claim construction forms a critical component of patent enforcement and invalidity challenges. Claim construction is a prerequisite for infringement analysis because the claims determine the scope of protection afforded to the patentee. Similarly, only after claims are construed to determine the invention can invalidity analysis proceed.

6.5.1.1 Procedure

Unlike the mechanism of a “Markman” hearing in the U.S., there is no separate procedural step for claim construction. Instead, claim construction is handled as part of the trial. Any disputes concerning the construction of claims will be framed as issues during the case management hearing. In the High Court of Delhi Rules Governing Patent Suits, 2022, it has been recommended that parties file a claim-construction brief before the case management hearing to enable courts and parties to assess whether there are any disputes in relation to the claims.102

6.5.1.2 Principles

In the context of India’s predecessor legislation, the Supreme Court of India has held that claims must be given an effective meaning and that the specification and claims must be examined and construed together.103 The Supreme Court followed English precedents when coming to this conclusion.

Under the Patents Act, 1970, the Delhi High Court, in F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd v. Cipla Ltd,104 held that one must undertake a “purposive construction” of the claims. The Delhi High Court drew inspiration from the concept of purposive construction that was formulated in the seminal English judgment Catnic Components Ltd v. Hill and Smith Ltd105 This principle is captured in the following two dicta in the Catnic Components case:

whether persons with practical knowledge and experience of the kind of work in which the invention was intended to be used, would understand that strict compliance with a particular descriptive word or phrase appearing in a claim was intended by the patentee to be an essential requirement of the invention so that any variant would fall outside the monopoly claimed, even though it could have no material effect upon the way the invention worked.

No plausible reason has been advanced why any rational patentee should want to place so narrow a limitation on his invention. On the contrary, to do so would render his monopoly for practical purposes worthless, since any imitator could avoid it and take all the benefit of the invention by the simple expedient of positioning the back plate a degree or two from the exact vertical.106

This principle of purposive construction was streamlined in the form of “Improver” questions in a subsequent judgment in the United Kingdom (U.K.)107 and later approved by the House of Lords.108 However, the U.K. Supreme Court, in Actavis UK Ltd v. Eli Lilly and Co.,109 disagreed with the earlier line of cases. According to the U.K. Supreme Court, this earlier line of case law on purposive construction conflated the issue of claim construction and infringement analysis.

The current standard in the U.K. requires a court to adopt a “normal interpretation” approach. For infringement purposes, according to the U.K. Supreme Court, one must examine whether the infringing device or process infringes the claim as construed by such normal interpretation. If not, the U.K. Supreme Court dictates that a court must thereafter assess whether the claim is infringed by equivalents. It has formulated a test for assessing such equivalents. The U.K. Supreme Court’s judgments in Actavis UK Ltd and subsequently in Icescape Ltd v. Ice-World International BV 110 have clarified that the normal interpretation of claims is also purposive. Such interpretations are purposive because courts are to construe claims as per their ordinary language, in their context (description and drawings) and in the light of the factual background (common general knowledge in the art).

There has been no subsequent judgment in India addressing these jurisprudential developments. However, since even the earlier rulings of the Supreme Court of India and the Delhi High Court were guided by the English precedents, it is expected that Indian courts will take a similar approach to claim construction.

6.5.2 Infringement analysis

6.5.2.1 What is “infringement”?

The Patents Act, 1970, does not separately define “infringement,” but courts regard any violation of the rights accorded under Section 48 of the Act as an infringement. Like most international jurisdictions, and consistent with Article 28 of the TRIPS Agreement, Section 48 of the Act confers an exclusive right on the patentee to prevent third parties from “making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing for those purposes” the patented product.111 In the case of process patents, the patentee has the exclusive right to prevent third parties from using the process and from “using, offering for sale, selling or importing for those purposes” the “product obtained directly by the patented process.”112 Committing these acts without the patentee’s consent constitutes infringement.

6.5.2.2 Exports as infringement

The Delhi High Court has held that the term “sale,” in the context of another provision of the Patents Act, 1970, includes “exports.”113 The Delhi High Court has also recently granted an interim injunction because exports from India would have also amounted to use in India.114

6.5.2.3 Proving infringement

A plaintiff must compare the alleged infringing product or process with the granted claim or claims to prove infringement.115 Claim construction precedes this exercise of comparison.116

The Patents Act, 1970, is silent on the doctrine of equivalence and other analogous concepts. The predecessor legislation allowed patentees to sue for infringement even when the infringers counterfeited or imitated the invention.117 Case law under the predecessor legislation suggested that courts would ignore “trifling or unessential variation.”118 Defendants were guilty of infringement if they made “what is in substance the equivalent of the patented article.”119 Case law under the current Act suggests that a similar approach may be followed.120

6.5.3 Defenses to infringement

The rights under Section 48 of the Patents Act, 1970, are expressly subject to other provisions of the Act. Section 107(1) states that all the grounds for revoking a patent for invalidity can be used as defenses to a claim for patent infringement. Defendants can, thus, contest the suit patent’s validity even without filing a counterclaim.

Section 107A recognizes the Bolar exception for defendants to use the patented product or process for developing information for regulatory filings both in India and abroad. The Delhi High Court’s judgment in Bayer Corp. v. Union of India121 carries a detailed discussion of the Bolar exception.

India follows the rule of international exhaustion regarding patents. Under Section 107A(b) of the Act, importing a duly authorized product from a foreign jurisdiction is not an infringement. Thus, the position is similar to that under the Trade Marks Act, 1999,122 but different from the domestic exhaustion rule followed under the Indian Copyright Act, 1957.123

Section 107(2), read with Section 47, contains well-known exclusions from the scope of a patent’s exclusivity, such as the research exemption, educational use and governmental use.

6.5.4 Counterclaim of invalidity

Defendants invariably file a counterclaim seeking revocation under Section 64(1) of the Patents Act, 1970. The grounds provided for revocation under Section 64(1) are exhaustive. There is a view that courts retain the discretion not to revoke a patent despite the fulfillment of one or more of the grounds under Section 64(1),124 though this does not seem to be the correct position in law. Proving any one of the grounds under Section 64(1) ought to lead to revocation of the patent.

The grounds for revocation usually taken in a counterclaim include lack of novelty or inventive step and non-patentable subject matter. It is also usual for defendants to support the grounds for revocation, especially in respect of lack of novelty and inventive step, by relying upon claims granted in other jurisdictions. If, in any other foreign jurisdiction, claims granted in corresponding patents are narrower than those granted in India, it is common for defendants in India to question the validity of the Indian patent by referring to such claims. Thus, it is advisable for patentee-plaintiffs in infringement actions in India to check whether the scope of claims in other significant jurisdictions differs, at least broadly, from that of the claims in India. If the patentee narrows the claims in other jurisdictions, it is advisable to make similarly narrower claims in India at the prosecution stage.

The citing of corresponding claims from foreign jurisdictions relates to the concept of “file-wrapper estoppel.” Although patent rights are strictly territorial, defendants argue that the patentee ought to be bound by statements, concessions and amendments made by the patentee before foreign patent offices concerning the same invention. Usually, such narrowing amendments in foreign jurisdictions, without corresponding Indian amendments, could adversely impact the grant of interim relief.

Another ground that defendants often rely upon is noncompliance with Section 8 obligations. Section 8(1) of the Act requires mandatory disclosure of the details of all corresponding foreign applications. Section 8(2) requires the filing of the prosecution history of corresponding foreign applications if so directed by the Indian Patent Office.

An issue frequently agitated in Indian courts, in invalidity challenges to pharmaceutical patents, concerns coverage and disclosure. In Novartis AG v. Union of India,125 the Supreme Court held that a patentee cannot contend that a patent’s coverage is more expansive than its disclosure. The following observation by Justice Jacob in the English case of European Central Bank v. Document Security Systems Inc. is often cited in the Indian context:

Professor Mario Franzosi likens a patentee to an Angora cat. When validity is challenged, the patentee says his patent is very small: the cat with its fur smoothed down, cuddly and sleepy. But when the patentee goes on the attack, the fur bristles, the cat is twice the size with teeth bared and eyes ablaze.126

Since claims are granted only upon an enabling disclosure, courts must presume that a prior patent discloses the claimed subject matter in an enabling manner. However, there have been various opinions expressed that the patent coverage could be wider than the disclosure, leading to multiple patents thereafter. The Delhi High Court has recently considered this issue in a series of interim orders, wherein the preponderance of the view favored the interpretation in Novartis.127 This view is presently the prevalent one.

6.6 Judicial patent proceedings and case management

6.6.1 Key features in patent proceedings

As in all civil cases, the onus of proving infringement is on the plaintiff suing for infringement.128 The court may shift the evidentiary burden and call upon the defendants to establish the noninfringement of process claims in specific circumstances consistent with Article 34 of the TRIPS Agreement. Section 104A of the Patents Act, 1970, provides for two situations in which the defendant can be asked to prove noninfringement of a process claim. One condition precedent common to both situations is that the defendant’s product must be identical to the product directly obtained by the patented process. Once this condition is fulfilled, the court retains the power to demand that the defendant prove noninfringement if the process is for obtaining a new product129 or if the plaintiff shows a substantial likelihood that the defendant is using the patented process and is unable to determine the defendant’s process despite reasonable efforts.

The court may not require the defendant to disclose its process if such disclosure would result in the disclosure of any trade, manufacturing or commercial secrets that form part of the defendant’s process, but only if the disclosure appears reasonable to the court.130 The use of confidentiality clubs, however, may aid even in such disclosure.131

6.6.2 Forum and locus standi to initiate infringement actions

A patent enforcement action under Section 104 of the Patents Act, 1970, can be initiated before a district court or higher. The court will try a patent suit as a commercial suit under the Commercial Courts Act, 2015.132 This also applies to a suit seeking a declaration of noninfringement.133 However, if a defendant in an infringement action counterclaims the patent’s invalidity, the suit and the counterclaim are automatically transferred to the High Court for further adjudication.134 A declaratory suit for noninfringement cannot question the patent’s validity.135The registered owner of the patent, or the assignee thereof, is entitled to sue for infringement. Section 109 of the Patents Act, 1970, provides that an exclusive licensee may sue for patent infringement but must implead the patent’s registered owner as a defendant. Under Section 110 of the Act, a person who has been granted a compulsory license may also sue for patent infringement if, upon notification of infringement to the patentee, the patentee fails to take action within two months.

6.6.3 Early case management

Once all pleadings are complete, the suit is listed before a designated commercial court single-judge bench in a case management hearing for framing issues. The court identifies, as precisely as possible, the issues that arise for determination; directs the filing of witness statements; and sets the schedule for trial. The Commercial Courts Act, 2015, prescribes short time limits for completing pleadings. Pending interim applications do not (and should not) delay the case management hearing for framing issues.

6.6.3.1 Pleadings and overall case schedule

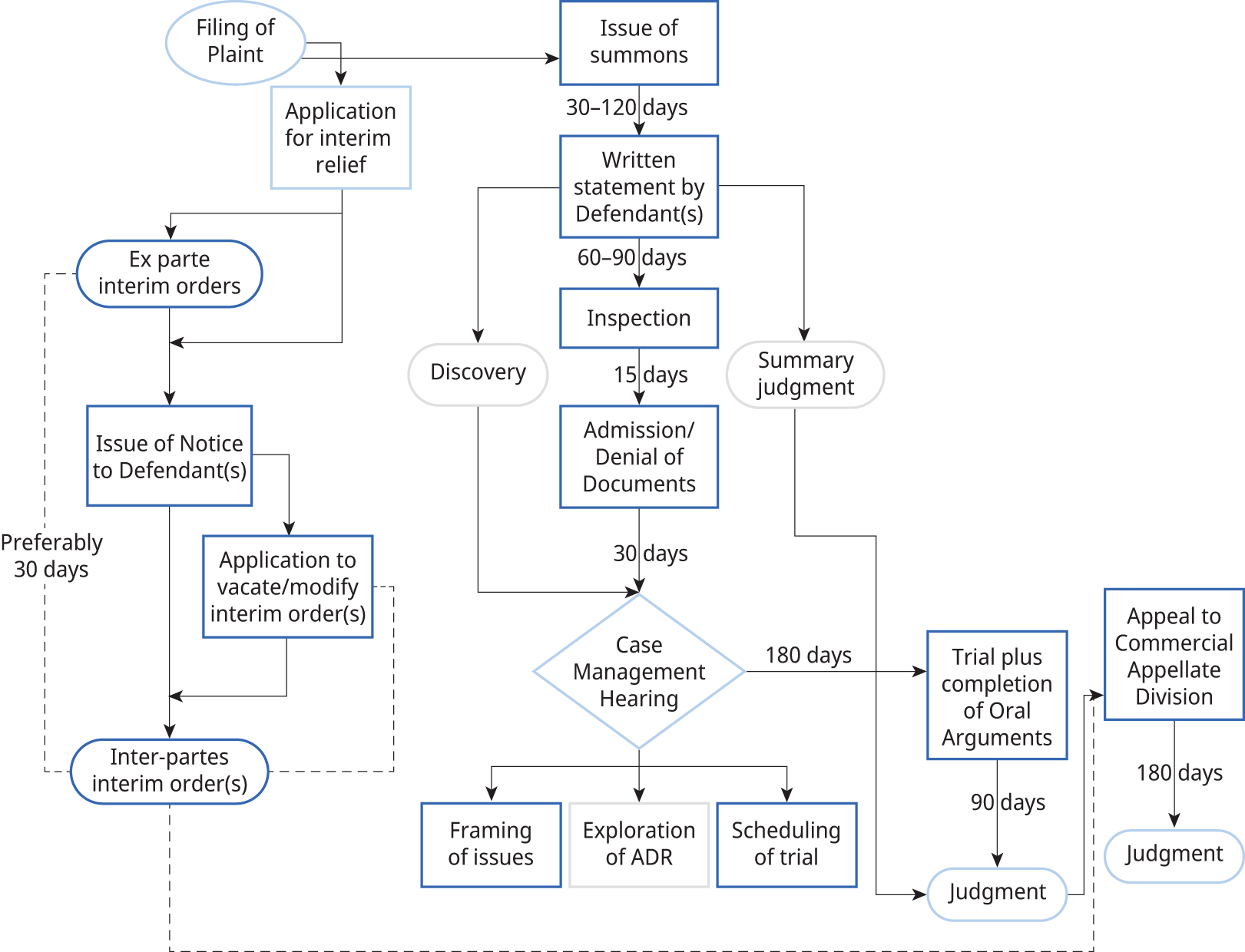

The Commercial Courts Act, 2015, fixes mandatory timelines for filing all pleadings. The Supreme Court of India, in SCG Contracts India Pvt. Ltd v. KS Chamankar Infrastructure Pvt. Ltd,136 confirmed that the timelines fixed under the Act are mandatory. The Act also prescribes a schedule for the entire case (see Figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4 Overall case schedule according to the Commercial Courts Act, 2015

Note: ADR = alternative dispute resolution.

The rigidity of timelines under the Act has been of some concern in patent litigation, given the technical complexity involved. However, most practitioners and litigants agree that, without fixed timelines, litigation tends to become unnecessarily protracted. The strict scheduling ensures that pleadings are completed on time and that trials are expedited. The real bottleneck is the final arguments post-trial, which has systemic causes: chiefly, the enormous number of unfilled positions of judges. Recent trends in filling these vacancies, coupled with specialized training in IP-related matters of judges rostered to IP cases, ought to address the bottleneck problem.

6.6.3.2 Case management hearing

Case management is mandatory under the Commercial Courts Act, 2015. The first case management hearing must be mandatorily held not later than four weeks from the date of filing of an affidavit of admission or denial of documents by the parties. It is intended for the court to engage in the early identification of disputed issues of fact and law, the establishment of a procedural calendar for the entire case (including trial and final hearing), and the exploration of the possibility of dispute resolution other than by trial.

6.6.4 Provisional measures

As a common-law jurisdiction, Indian courts are vested with extensive discretionary powers to grant interim relief. The usual determinants apply: whether the plaintiff has a prima facie case, where the balance of convenience lies, and to whom irreparable injury is likely if the order is or is not granted. An interim order may subject the plaintiff to conditions, including security. Injunctions can be tailored to suit the remedy.137

In general, interim reliefs can be in various forms, including interim injunctions; Mareva orders or freezing orders; Anton Piller orders, where local commissioners (LCs) are appointed with powers of search and seizure; and directions for keeping accounts. Under Order XXXIX(1)–(2) of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 [hereinafter the “Code of Civil Procedure”], patentees may also seek interim and ad interim injunctions. Indian courts have regularly considered the grant of interim injunction orders, Anton Piller orders, Mareva orders, Norwich Pharmacal orders or John Doe orders in fitting cases.

It is usual to seek even ex parte ad interim relief in suits for patent infringement. In some cases, where the patent has been tested multiple times in litigation, courts usually even grant the ad interim injunction ex parte; there is no strict rule. For instance, in the case of SEPs, defendants are usually called upon before the grant of an injunction for a response as to whether they are willing to take a license on fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms.

Irrespective of the outcome of the interim proceedings, the parties (usually the unsuccessful party at the interim stage) usually seek an expeditious trial and final hearing. In fact, in one case where the interim injunction was granted in favor of the patentee (i.e., Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. v. Glenmark Pharmaceuticals),138 the Supreme Court allowed the sale of the existing stock already manufactured by the defendant and directed a day-to-day trial, saying that this was in the national interest, one that demanded a suitable commercial environment for the immediate resolution and adjudication of contentious commercial cases.139 In that case, due to the intervention of the Supreme Court, the time from the suit’s filing to final judgment was only about 30 months. The trial concluded in a record time of less than 30 days. Final arguments were heard for three weeks, and judgment followed very soon thereafter. The Supreme Court has also issued general directions for such expedited hearings in other patent matters.140

In cases where a patent has been tried and tested in prior litigation, courts have not hesitated to grant interim injunctions, though the defendant may be permitted to exhaust existing stocks along with accounts. Some perceive the Delhi High Court to be quite liberal in granting interim injunctions to patentees, though there have been some instances in which the court has refused interim injunctions owing to the complexity of the invalidity defense. In other cases, the court has crafted alternative arrangements for the interim period. Where an interim injunction is refused, courts almost always direct the defendant to maintain and file accounts.

6.6.4.1 Governing legal standards and burdens

Courts see growing numbers of patent litigation, with a corresponding increase in the grant of injunctions (both permanent and interlocutory). Temporary injunctions are regulated by Sections 94 and 95 and Order XXXIX of the Civil Procedure Code. The substantive law on temporary and perpetual injunctions can be found in Sections 36–42 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963.

The general principles for grant or denial of such interim orders are well known: a prima facie case, the balance of convenience, irreparable injury and public interest factors.141 Indian courts have derived principles following the decision of the House of Lords in American Cyanamid v. Ethicon Ltd,142 though the Supreme Court of India has observed that the relatively diluted standard of “prima facie case” in American Cyanamid will not apply in India.143 Similarly, whereas American Cyanamid suggests that more weight must be attached to patents granted after a detailed examination procedure, Section 13(4) of the Patents Act, 1970, and some judicial precedents in India suggest that this proposition is inapplicable to Indian patent law.144

6.6.4.1.1 Prima facie case

The prima facie case requirement is used to discern whether the plaintiff has a reasonable case on merits. It does not finally or conclusively decide issues of fact. It weeds out frivolous or vexatious claims – ones manifestly without merit. As part of this assessment, courts also assess whether defendants have a credible challenge to the suit patent’s validity.145

Initially, in India, a few judicial pronouncements referred to a six-year rule (i.e., a presumption that there could be an increased probability a patent could be treated as valid on the expiry of six years from the date of grant). The genesis of the six-year rule approach can be traced to the Madras High Court’s ruling in Manicka Thevar v. Star Ploro Works case,146 which was subsequently picked up in other judgments.147 However, none of the provisions of law appears to suggest or support this numerical fixation with six years. The Manicka Thevar case was subsequently held not to be correct law by another division bench of the Madras High Court.148 In F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd v. Cipla Ltd, a single judge of the Delhi High Court also held that there was no basis for the six-year rule and rejected the application of the said rule in patent cases.149 Thus, one will not find a discussion of any such six-year rule in most recent patent cases across India.

6.6.4.1.2 Balance of convenience and public interest

The second requirement for the grant or denial of an interim injunction is that the balance of convenience must be in favor of granting an injunction. The court, while granting or refusing to grant an injunction, should exercise sound judicial discretion to compare and determine the amount of mischief or injury likely to be caused to the respective parties if the injunction is refused and if it is granted. The court would weigh competing possibilities or probabilities.

In India, public interest has been recognized both as a separate factor and as a factor read into the test for the balance of convenience.150 For instance, the public interest in enabling access to lifesaving drugs (both supply and pricing considerations) has been considered a relevant factor when deciding on an application for an interim injunction.151 Recently, given the influence of comorbidity factors such as diabetes and obesity in the severity of COVID-19 infections, the pricing of antidiabetic medications was considered one of the relevant factors when assessing interim injunction applications.152

The defense of public interest is not a complete exception to a legally valid patent and must not be too broadly interpreted, as it would undermine “the rights granted by the sovereign towards monopoly.”153 The Delhi High Court has recognized that upholding the enforcement of patents is also in the public interest.154 Thus, often, public interest factors are considered along with the prima facie strength of the infringement case or the invalidity defense.155