Standards underpin everything that connects us, from video streaming to connectivity (think of 5G), including the Internet of Things. However, participating in a standardized technology field means navigating a complex web of agreements and disagreements. Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) protect the technologies you must license if you want your standard-compliant device to work. And while standardization provides great benefits, SEP licensing is not always straightforward.

To illuminate the ongoing debate, WIPO assembled the first Symposium on Standard Essential Patents, which ran in Geneva from September 18 to 19, 2025. Academics, judges, diplomats, economists, government officials and licensing professionals were joined by licensors such as Philips, Qualcomm and Nokia, major licensees and innovators such as Apple or Volkswagen, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) such as Fairphone and NuCurrent (click here for the full lineup).

For two days, the conference hall echoed with conversation about what fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) licensing terms may mean in 2026 and beyond. Some 300 participants attended the event in person, with more than 900 joining online from almost 90 countries.

No recordings are publicly available, which illustrates how the discussion can oscillate between transparency and confidentiality. However, WIPO Magazine was there with an ear tuned to messages for SMEs. So, if you want to know how to get better at making FRANDs, here are our takeaways. Care to dance?

Determining FRAND licensing terms for SEPs

A key issue is that there is no objective measure of what the FRAND royalty rate should be, whether for a portfolio of SEPs or for all the SEPs covering a particular standard. FRAND is in the eye of the beholder.

As Carsten Fink, Chief Economist at WIPO, explained, the goal is to balance innovation incentives. “In reality, however, it is hard to determine what actually is fair and reasonable among ‘FRANDs’.”

There is no standard for determining FRAND terms; FRAND is not a specific value, but rather a range. Negotiations generally take place behind closed doors between implementers, licensors and their lawyers, who try to hammer out what constitutes fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory licensing terms.

SMEs need cost-effective means to understand whether an offer is indeed FRANDly.

Methodologies have emerged to guide negotiations, and knowing your way around them will put you on more solid ground. WIPO will publish a detailed study on the methods presently applied, but the symposium and its panel discussions offered a bird’s eye view of current practice.

A common market-based approach to figuring out FRAND terms is comparable licensing, which takes similar, prior agreements as benchmarks. The other main method is the top-down approach, which starts by determining an aggregate royalty rate for a standard, splitting the cake between the various holders of SEPs. Lastly, the aim of the bottom-up methodology is to isolate specific technical contributions by examining the alternatives that existed when the standard was set and the added value of a particular innovation.

Negotiating SEP licenses

Even with economic frameworks, actual SEP licensing involves parties with potentially competing interests and information asymmetries. A symposium panel featuring officials from Philips, Qualcomm, Lenovo and Deutsche Telekom offered a high-level perspective on real-world negotiations and how licensors approach licensees.

Having negotiated licenses since 2005, often with smaller businesses, a senior representative for Philips described the process as a learning cycle. “New companies need to build an understanding of how licensing works. You need to build trust mutually.”

Asked how difficult it is to negotiate and build simultaneously, panelists noted that markets typically mature over time. “It was difficult initially to get automotive players’ attention,” they said. “Today it’s much smoother. The IoT [Internet of Things] market is currently going through that learning curve.”

A Qualcomm representative agreed that time and developed relationships are factors. Speaking about their licensing agreements, they said: “Most are renewals now and those are much easier. We are seeing fewer licensees challenge Qualcomm. Instead, they want us cross-evaluating their portfolio.”

SEPs and data: hurdle or tool?

Nonetheless, the process remains contentious, as shown when the panel turned to the role of data in SEP licensing and, specifically, claim charts, which map patent claims to specific elements of a standard.

Claim charts are widely used to demonstrate essentiality in licensing discussions. While they can support negotiations, they can be difficult for inexperienced parties to comprehend and sometimes slow deals down. One panelist noted: “A more lightweight approach often works better.”

Another panelist was even more direct: “Claim charts can be used as a negotiation tactic to overpower. Low-quality charts are tiresome to review.” If that burden weighs on large technology companies, the impact on SMEs is even greater.

SEP litigation: feature or failure?

Tensions crystallized around litigation’s role in the system. Is it a feature of SEP licensing or evidence of its failure?

“It depends on the perspective,” one panelist replied, adding that litigation can function either as an “emergency brake” or as a “steering wheel”.

For many SEP-holders, injunctions – and litigation more broadly – remain necessary tools to ensure that unwilling licensees eventually engage in meaningful negotiations. Without the possibility of such judicial remedies, some licensors argued, implementers may simply delay or avoid taking a license altogether.

Implementers, however, emphasized the existential risks that injunctions can create, especially when essential components are involved. Any infringing components can jeopardize an entire product line, such as that of a car.

Both sides have legitimate concerns: patent-holders need mechanisms to prevent holdouts, while implementers need protection against opportunistic behavior.

Yet multijurisdictional litigation can lead to friction. A panel discussion involving six judges from China, Colombia, India, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Unified Patent Court in Europe, moderated by Eun-Joo Min, Director of the WIPO Judicial Institute, showed that approaches differ significantly.

Throughout the symposium, a shared view emerged on litigation being a ‘last resort’.

The panel discussed matters such as the availability of injunctions, setting FRAND rates on a global level, newly created judicial doctrines such as interim licenses, and whether the FRAND undertaking is based on contract or competition law.

When it comes to “battles of jurisdictions” through anti-suit and anti-anti-suit-injunctions, their influence on global trade can result in disputes between World Trade Organization (WTO) members, as illustrated by the account of Counsellor Roger Kampf on the recent cases arbitrated within WTO.

Still, throughout the symposium, a shared view emerged on litigation being a “last resort”, as a representative from one major SEP-holder noted in the keynote panel. Since 2017, the company in question has signed or renewed more than 250 license agreements, with fewer than 1 per cent of them involving litigation.

This suggests that, while courts play a vital role, most FRAND deals are reached through negotiation. For SMEs in particular, litigation represents an existential threat that is best avoided – the evidence shows that it usually can be.

Alternative dispute resolution in FRAND disputes

Throughout the symposium, participants highlighted the potential of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) to address many of the challenges inherent in FRAND negotiations, especially those spanning multiple jurisdictions.

“Independent, legally binding arbitration is the best and fairest solution,” one panelist observed. “There should be a panel of three arbitrators – both parties nominate one, then the third arbitrator is nominated by these two or the arbitration institute.”

In addition, mediation can be a valuable tool for SMEs that need cost-effective means to understand whether a proposed offer is indeed FRAND-compliant.

SME must rely on fair dealing more than anyone, because to take on any company of any size is existential to a smaller company.

In the dedicated ADR panel moderated by Heike Wollgast of the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center (WIPO AMC), all noted a sharp increase in demand. WIPO AMC has mediated 85 SEP cases across more than 20 jurisdictions, achieving a settlement rate of approximately 70 per cent.

Shortly after the symposium, WIPO AMC launched the WIPO Mediation Pledge by SEP holders to IoT SMEs. Signatories commit to a “mediation-first” approach towards SMEs that make or sell IoT devices, with WIPO as a venue for amicable settlement, thereby supporting smaller players.

Transparency vs. confidentiality among ‘FRANDs’

One challenge mentioned in practically every session was that parties need information to negotiate effectively without revealing their full competitive strategy. ADR mechanisms – and in some jurisdictions, court-ordered measures like pre-action disclosure – can help to bridge this gap.

Sharing anonymized information about comparable agreements under controlled conditions helps parties assess whether proposed terms are reasonable. As one panelist noted, when “a willing licensee is simply anxious about whether terms are fair”, structured transparency becomes essential to moving negotiations forward.

Fair SEP for SMEs - small players in a big game

The challenges compound for smaller companies. When Apple and Qualcomm negotiate, they have leverage and teams of specialists. When a startup enters the same landscape, it has to rely on fair dealing more than anyone, because “to take on any company of any size is existential to a smaller company,” Jacob Babcock, CEO of NuCurrent, said on the symposium’s SME panel.

Babcock’s mid-sized company holds 450 patents and spends 80 per cent of its budget on research and development (R&D), developing wireless charging technology for medical implants and consumer devices. This makes NuCurrent an implementer and a licensor – not an unusual position for innovative SMEs.

“We work with the Ericssons and the Philips and the Gs [mobile communication standards like 4G and 5G] of this world,” he said, warning that it can be costly in at least two ways. “Standards participation requires not just fees but enormous engineering time and specialized personnel who can navigate standards-setting committees.” Moreover, “you’re dancing with the elephants, so you have to be very careful when to declare SEPs.”

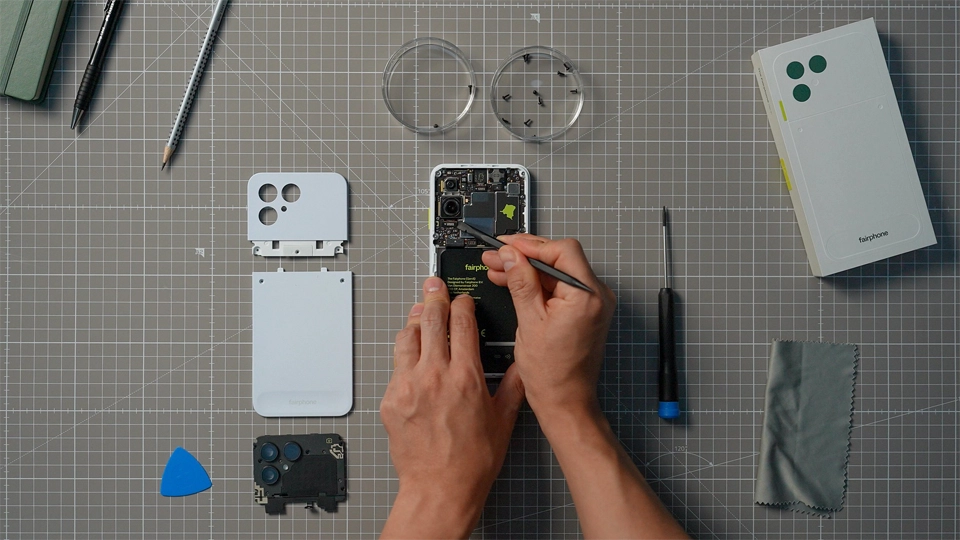

Lukas Johnson-Hecker from Fairphone, a sustainable smartphone manufacturer, offered another perspective on SME participation. The European Union’s eco-design resolution mandates that specific device components, such as batteries, be replaceable. “We’ve been doing that at Fairphone since 2013, so SMEs can play a role in standardization by pushing the boundary in regulation.”

He agreed with Babcock that there are systematic disadvantages: “To a large degree, small implementers just lack the sophistication to navigate the landscape, and it needs resources that I just don’t have.”

Johnson-Hecker also found that smaller implementers tended to be discriminated against on rates due to a lack of transparency or confidentiality. “The willing licensee is often getting the worst rates [per unit]. When interjecting, we face overly aggressive NDAs [non-disclosure agreements] that prevent me from showing evidence to regulators.”

This raised a question sometimes posed about SEP licensing: is it a “tax on innovation”?

Babcock rejected the characterization. “It’s a little unfair to call it a tax when so much value is being put on the table.”

Johnson-Hecker also rejected the notion because there is “undoubtedly innovation being brought to market for implementers to build on”. However, he added: “We have no way of calculating these costs when developing the product. The claims come after the product is on the market.”

Robert Pocknell from N&M Consultancy was direct. “I’m disappointed to be here still talking about these issues without having found comprehensive solutions. Smart lightbulb inventors using Wi-Fi were asked to pay SEP licenses and abandoned development out of fear. Small firms simply stop innovating rather than navigate the complexity.”

Tools for SMEs navigating SEP licensing

But the panel also identified solutions. Pocknell highlighted patent pools, where multiple rights-holders aggregate patents for collective licensing. “Transparent pricing, standard terms, one negotiation instead of dozens. For smaller companies, pools dramatically reduce complexity.”

Johnson-Hecker agreed that pools bring transparency but noted that “larger SEP-holders are often outside these pools, hampering their comprehensiveness”.

Joint licensing negotiation groups (LNGs) also came up. Pocknell thought them “good news generally” since it makes sense that implementers gather to have one negotiation. However, the danger of collusion and price-fixing makes it a delicate task to ensure that their setup, procedures and operational rules conform to competition law.

Johnson-Hecker agreed on the usefulness of LNGs, saying that they “would be a net positive for the licensing landscape”, while others questioned the rationale behind such licensee coordination mechanisms.

Patent pools can be incredibly helpful for SMEs that may or may not have the resources to secure an untold number of licenses.

Going back to pools, Babcock found a different limitation, although he admitted that he was speaking about a “very narrow set” of pools in which his company is involved. “The division of economics is biased towards volume, not quality,” he said. “If you have dozens, not hundreds of patents to contribute, even if they’re foundational, you may not receive fair value”, meaning that averaging mechanisms can systematically undervalue foundational contributions.

Nonetheless, if they work, patent pools can help to reduce complexity. Some participants even said that patent pools are their primary way to license. This echoed strong views from policymaker Chris Hannon of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). He found patent pools “consistent with the USPTO’s view that regulatory interventions are a last resort”, with the Office having long championed industry-led solutions.

“With that in mind, I would be remiss not to mention and encourage the establishment and use of patent pools in the SEP arena,” he said, citing drastically reduced transaction costs and negotiation complexity through increased transparency regarding royalty rates, questions of essentiality, and patent scope.

“This can be incredibly helpful for SMEs that may or may not have the resources to secure an untold number of licenses to practice the standard in good faith,” Hannon said.

A representative from Avanci, which operates patent-licensing platforms, underlined pools’ efficiency: “Avanci’s 4G program has licensed more than 110 automotive brands to more than 60 patent-holders. It’s simpler and more efficient to sign one license than 80 separate agreements.”

An executive of Sisvel, which has been using pools since 1982, underlined the need for transparency and the nature of compromise. While noting that the “success of a patent pool is making everyone equally unhappy”, suggesting that pools can rarely deliver perfect outcomes for any single stakeholder, he stressed that they still offer broadly acceptable, industry-led and therefore workable solutions for the wider ecosystem.

Policies for Standard Essential Patents

The panel on policy and regulation brought together government and institutional representatives: the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA), the European Commission (EC), the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS), the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) and the USPTO.

Panelists acknowledged the possibilities and limitations of regulatory intervention in this field. One speaker noted that “there is not going to be a legislative result that is going to satisfy everyone”.

At the heart of all SEP conversations lies something deeply human: trust.

Another panelist mentioned a less interventionist approach: “We’re not looking to regulate the market but increase information to overcome issues like transparency and information asymmetry.”

A common theme emerged: while regulatory measures may not resolve every tension in the SEP ecosystem, public institutions can provide legal certainty, facilitate information exchange and support smaller actors that may struggle with the intricacies of SEP licensing.

Alfred Yip, Director of IPOS International, also reminded participants that jurisdictions cannot resolve interoperability challenges alone but must learn from fellow offices and global stakeholders. “At the heart of all SEP conversations lies something deeply human: trust,” he said. “Neutrality is about setting up systems that all parties trust.”

The role of WIPO in the SEP ecosystem

The need for a neutral, global forum was a recurring theme, acknowledged on day one when a keynote speaker said that “SMEs struggle with these issues”, before pointing them to “some of WIPO’s materials because the neutrality is outstanding”.

This was in reference to the WIPO Strategy on Standard Essential Patents, currently at its midpoint. Andras Jokuti, presenting for WIPO, emphasized the organization’s unique positioning: “We’re a global, specialized United Nations agency for IP, operating under neutrality and accountable to all Member States, including developing economies.”

The strategy, at nine pages, calls for establishing a platform for dialogue, serving as a hub for knowledge and data, functioning as a venue not only for ADR but also for deal facilitation, and providing services directly accessible to stakeholders.

Other WIPO initiatives for actors in the SEP ecosystem include the SEP Case Law Collection on WIPO Lex. Since April 2025, patents that have been declared as essential to technological standards adopted at three Standard Developing Organizations (SDOs) are now also marked as such and searchable in PATENTSCOPE.

Another keynote speaker suggested that WIPO could expand its role by proposing “standardized licensing agreement templates that parties could voluntarily adopt, creating common frameworks without mandating specific terms”. “WIPO would be an ideal forum for this,” they continued, “because WIPO is a genuinely global organization.”

Entering the SEP space

What emerged during the WIPO Symposium on SEPs over those two September days was paradoxical but instructive for smaller players: the system is complex and tilted toward those with resources, yet with the proper preparation and partnerships, it is navigable. You’re dancing with elephants, certainly. But you’re not dancing alone.

Patent pools, licensing groups, arbitration mechanisms and neutral forums such as WIPO exist precisely because these challenges are shared. The key is not to avoid the dance – standards are essential for innovation – but to enter it with open eyes, partners alongside you and the knowledge that even elephants must follow the steps of what is genuinely fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory.

If you are looking to enter the SEP space, be prepared for tough negotiations and possibly lengthy information gathering. Use all the available resources from institutions such as WIPO, government agencies and other organizations. Keep an eye on regulation and take part in it where you can.

Be willing to listen to the licensor and use their experience where offered, yet consider joining the dance with other smaller players, playing fair all the way. Making FRANDs has never been easy – but trust and openness for dialogue go a long way.

Find all information on the past Symposium on Standard Essential Patents and more information on SEPs at WIPO.