This statistical audit was conducted by Jaime Lagüera González, Panagiotis Ravanos, Michaela Saisana, Oscar Smallenbroek, Alberto Guidi and Alexandre Canario Borrega, European Commission, JRC, Ispra, Italy.

Robust and reliable monitoring frameworks are the highways to better policymaking. As much as in other socio-economic fields, understanding and modeling innovation at both national and global levels is crucial for identifying emerging trends and informing future strategies, but it also presents conceptual and practical challenges. These include, for example, those related to data quality and methodological choices. Addressing these challenges is essential for ensuring that policymakers have access to robust and actionable information to drive their way towards effective innovation policies. The 18th edition of Global Innovation Index (GII) 2025 addresses these issues by organizing data from 139 economies across 78 indicators into a structured framework of 21 sub-pillars, seven pillars, two sub-indices, and an overall index. This appendix delves into the practical challenges of constructing the GII, examining the statistical robustness of the conceptual framework and the robustness of the calculations and assumptions used to determine the final rankings.

Statistical soundness should be regarded as a necessary but not sufficient condition for a sound GII, since the correlations underpinning the majority of the statistical analyses carried out herein need not "necessarily represent the real influence of the individual indicators on the phenomenon being measured" (

The European Commission's Competence Centre on Composite Indicators and Scoreboards (CC-COIN) at the Joint Research Centre (JRC) in Ispra, Italy, has been invited to audit the GII for a 15th consecutive year. As in previous editions, the present JRC-COIN audit focuses on the statistical soundness of the multilevel structure of the index, as well as on the impact of key modeling assumptions on the results.

As in the previous GII reports, the JRC-CC-COIN analysis complements the economy rankings of the GII, the Innovation Input Sub-Index and the Innovation Output Sub-Index with confidence intervals, in order to allow a better appreciation of the robustness of these rankings to the choice of computation methodology. The JRC-CC-COIN analysis also includes an assessment of the added value of the GII and it supplements the GII scores with a measure of the "distance to the performance frontier" of innovation through the use of data envelopment analysis.

Step 1 Conceptual consistency

compatibility with existing literature on innovation and pillar definition

use of scaling factors per indicator to present a fair picture of economy differences (e.g., GDP, population)

Step 2 Data checks

check for data timeliness (94 percent of available data refer to 2021 or a later year)

inclusion requirements per economy (availability of ≥66 percent for the Input and the Output Sub-Indices separately and data availability for at least two sub-pillars per pillar)

check for reporting errors (interquartile range)

outlier identification (skewness and kurtosis) and treatment (winsorization or logarithmic transformation)

direct contact with data providers

Step 3 Statistical coherence

treatment of pairs of highly collinear variables as a single indicator

assessment of grouping of indicators into sub-pillars, pillars, sub-indices and the GII

use of weights as scaling coefficients to ensure statistical coherence

assessment of arithmetic average assumption

assessment of potential redundancy of information in the overall GII

Step 4 Qualitative review

internal qualitative review (by WIPO in partnership with the Portulans Institute, the GII Corporate and Academic Network partners, as well as the GII Advisory Board members)

a one-off qualitative audit (by the WIPO Internal Oversight Section)

(2)Available at: https://www.wipo.int/documents/d/about-wipo/docs-en-oversight-iaod-audit-audit-gii.pdf, IOD Ref: IA 2022-03, April 14, 2023. external qualitative review (by JRC-COIN and international experts)

Source: European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2025.

Conceptual and statistical coherence within the GII framework

The GII model was assessed by the JRC-COIN in June 2025. Suggestions for fine-tuning certain aspects were taken into account in the final computation of the rankings during an iterative process with the JRC-COIN aiming to set the foundations for a balanced index. This four-step process is outlined in Box 1.

Step 1: Conceptual consistency

A total of 78 indicators were selected for their relevance to specific innovation pillars, based on a literature review, expert opinion, economy coverage and timeliness. To present a fair picture of economy differences, indicators were scaled either at source or by the GII team, as appropriate and where needed. For example, Venture capital deals received, deal count (indicator 4.2.2) is expressed as number of deals per billion PPP$ GDP, while Government funding per pupil at secondary level (indicator 2.1.2) is expressed as a percentage of GDP per capita. As of 2023 and on the advice of JRC-COIN, the GII developers normalize all 78 indicators to a 0–100 range which facilitates their individual contributions to the overall index score.

The 2025 edition of the GII includes some changes to the indicators.

The methodology for calculating some indicators has changed. In particular, the definition of indicator 3.1.1 ICT Access now includes a component on the availability of 5G connectivity, in addition to 3G and 4G/LTE connectivity. Also, 6.1.2 PCT patents is now counted by origin of the inventor rather than by origin of the first-named applicant. This methodology for counting patents is also followed by other innovation monitoring frameworks such as the European Innovation Scoreboard (see, e.g.,

European Commission, 2024 European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (2024). European Innovation Scoreboard. Publications Office of the European Union, available at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/779689 ).The source for all four Venture capital (VC) indicators used in the index (indicators 4.2.2, 4.2.3, 4.2.4 and 4.2.5) has changed. The developers have opted for using the Pitchbook database to improve data coverage, particularly for middle and low-income economies.

As a result of the change in data source, indicator 4.2.5 (corresponding to the former 5.2.4 Joint venture/strategic alliance deals) has been transferred to pillar 4 Market sophistication from pillar 5 Business sophistication and also changed methodology, now reflecting VC deals that include co-investors by companies. Its transfer to pillar 4 is justified by the grater conceptual fit to sub-pillar 4.2-Investments, where other VC indicators are also present.

In sub-pillar 3.1 Information and communication technologies (ICTs) former indicator 3.1.4 (E-participation) has been dropped. This indicator is part of the UNDESA Online Service Index, which features already in the GII as indicator 3.1.3 Government's online service. The rationale for dropping E-participation was to reduce the possibility of double counting of information, as the E-participation component has a weight of 35% of the Online Service Index.

Indicator 5.2.3 University industry and international engagement has been introduced to sub-pillar 5.2. Innovation linkages, featuring the international and industry linkages of top universities in the country.

Finally, in sub-pillar 5.1 Knowledge workers, indicator 5.1.3 Youth demographic dividend replaces the former Firms offering formal training, based on concerns about the timeliness and future data availability of the latter.

The above changes highlight the developers' commitment to rigorously monitoring, evaluating, and refining both the theoretical framework and the data sources underpinning the index. This continuous improvement process ensures that the index delivers a reliable, accurate and timely assessment of innovation performance, empowering policymakers with reliable insights to drive evidence-based decision-making.

Step 2: Data checks

The data used for each economy were those most recently released within the period 2015 to 2025 94 percent of the available data refer to 2021 or a later year. With regards to the inclusion of countries in the GII, the 2025 edition follows the criteria adopted in 2016,

In practice, data availability for all economies included in the GII 2025 is quite satisfactory: At least 80% of data is available for 79% of the economies covered (equivalent to 110 economies out of 139), while 82% of the considered indicators are available for at least 75% of the 139 economies covered. This highlights the significant efforts conducted by the GII in promoting continuous data monitoring and collection in the realm of innovation-related variables. There are only two indicators for which the share of missing data is relatively high (4.1.3 Loans from microfinance institutions and 7.2.3 Entertainment and media market, for which data are available for 47% and 45% of the 139 countries respectively).

Potentially problematic indicators that could bias the overall results were identified on the basis of two measures related to the shape of the data distributions: skewness and kurtosis. In 2011, a joint decision by the GII team and the JRC-COIN determined that values would be treated if an indicator had absolute skewness greater than 2.0 and kurtosis greater than 3.5.

for indicators with absolute skewness greater than 2.25 and kurtosis greater than 3.5, apply either winsorization or the natural logarithm (in cases of more than five outliers);

for indicators with absolute skewness less than 2.25 and kurtosis greater than 10.0, produce scatterplots to identify potentially problematic values that need to be considered as outliers and treated accordingly.

For a total of 23 indicators, one up to 5 values were winsorised, while for an additional 11 indicators (2.3.3 Global corporate R&D investors, 4.2.3 Late-stage VC deal count, 4.2.4 VC investors, 4.3.3 Domestic market scale, 5.2.5. Patent families, 5.3.1 Intellectual property payments, 6.1.1 Patents by origin, 6.1.2 PCT patents by inventor origin, 6.3.1 Intellectual property receipts, 7.1.4 Industrial designs by origin, and 7.3.3 Mobile app creation) the natural logarithm was applied. For three of these five indicators (4.2.4 VC investors, 4.2.3 Late-stage VC deal count, and 5.2.5. Patent families) the values of skewness and kurtosis did not abide by the set thresholds after applying the natural logarithm transformation.

Compared to the previous edition of the GII in 2024, there were six additional indicators that needed a natural logarithm treatment (11 versus five last year). The JRC guidelines for data treatment are governed by the principle of least intervention in the distribution of the data and put forth winsorisation as a first treatment followed by natural logarithm transformation. To reduce the indicators treated by the latter, the JRC would like to suggest increasing the number of maximum winsorised data points for the GII indicators by two from to five to seven. This corresponds to the upper 5% (7/139) of the distribution with 139 countries, that is to say, values are trimmed up to the 95% percentile if needed. Tests conducted by the JRC indicate that increasing the number of winsorized points would eliminate the need to apply the natural logarithm to 8 of the 11 indicators. For the remaining three indicators (4.2.3 Late-stage VC deal count, 4.2.4 VC investors, and 5.2.5. Patent families) the logarithmic transformation would bring skewness and kurtosis values within the recommended thresholds.

Step 3: Statistical coherence

Weights as scaling coefficients

The JRC-COIN and the GII team jointly decided in 2012 that weights of 0.5 or 1.0 were to be used as scaling coefficients and not importance coefficients, with the aim of arriving at sub-pillar and pillar scores that were balanced in their underlying components (i.e., that indicators and sub- pillars can explain a similar amount of variance in their respective sub-pillars/pillars).

As a result of this analysis, two sub-pillars are also given a weight of 0.5, namely 7.2 Creative goods and services and 7.3 Online creativity.

Despite this weighting adjustment, two indicators (5.3.4 FDI net inflows and 6.2.1 Labor productivity growth) were found to be non-influential in this year's GII framework, meaning that they could not explain at least 9 percent of economies' overall variation in the respective sub-pillar scores.

As previously noted, a weak statistical relationship does not imply that an indicator is conceptually unsuitable. Rather, it reflects the amount of information (or variability) that the indicator contributes to the overall index. Specifically, the weak correlation between the FDI net inflows and Labour productivity indicators and the GII indicates only a limited relationship, without suggesting any causality or its absence. The JRC-COIN encourages the developers to carefully monitor the statistical fit of these indicators in future editions of the index and to thoughtfully assess their impact on economies most affected by their inclusion in the framework.

Building on this analysis, the indicator 5.1.3, Youth demographic dividend, warrants some special attention. The indicator's statistical fit with the remaining GII variables is rather particular: It shows a statistically significant negative correlation (< –0.4) with all other indicators within the sub-pillar 5.1 Knowledge Workers, as well as with the GII index, with which it has a negative correlation coefficient of –0.76. Similarly weak correlations are observed with many other indicators across the GII framework—62 out of 77 indicators show a negative correlation below -0.3 with this measure.

Importantly, this indicator has a pronounced regional impact, as it tends to favor African countries by effectively providing a “bonus” that reflects their unique demographic advantage. The youthful populations in many African economies position them with significant potential for innovation and economic growth in the years ahead, driven by their expanding human capital. This regional dimension highlights the indicator’s role in capturing forward-looking innovation capacity that may not be fully reflected by other measures in the index. While the JRC-COIN acknowledges the conceptual importance and future-oriented nature of the Youth Demographic Dividend, these comments are strictly statistical. The strong negative correlations observed can reduce the framework’s ability to effectively differentiate and rank countries and increase sensitivity to weighting choices. Therefore, the JRC-COIN encourages the developers to further delve into the insights that stem from including the Youth Demographic Dividend indicator in the GII framework and to carefully consider retaining the indicator as a critical contextual component in future index editions—particularly for its value in highlighting the innovation potential of regions with youthful demographic profiles, such as Africa.

The remaining 71 indicators out of the 78 in total were found to be sufficiently influential - in the statistical sense- in the GII framework.

Principal component analysis and reliability item analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to assess the extent to which the conceptual framework is confirmed by statistical approaches. PCA results confirm the presence of a single latent dimension in each of the seven pillars (one component with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0) that captures between approximately 61 percent (pillar 3: Infrastructure) and up to 81 percent (pillar 1: Institutions) of the total variance in the three underlying sub-pillars. Furthermore, results confirm the expectation that in the majority of the cases, the sub-pillars are more closely correlated with their own pillar than with any other pillar and that all correlation coefficients are close to or greater than 0.70 (Appendix Table 2).

The five input pillars share a single statistical dimension that summarizes 80 percent of the total variance and the five loadings (correlation coefficients) of these pillars are very similar to each other. This similarity suggests that the five pillars make a roughly equal contribution to the variation of the Innovation Input Sub-Index scores, as envisaged by the development team. Consequently, the reliability of the Input Sub-Index, measured by Cronbach's alpha value, is very high at 0.93 – well above the 0.70 threshold for a reliable aggregate (

The two output pillars – Knowledge and technology outputs and Creative outputs – are strongly correlated with each other (0.88); they are also both strongly correlated with the Innovation Output Sub-Index (0.96 and 0.97).

Finally, the two sub-indices are equally important in the overall GII. The GII is built as a simple arithmetic average of the Input Sub-Index and the Output Sub-Index. In fact, the Pearson correlation coefficients of the two sub-indices with the GII (around 0.97 in both cases), and the correlation between themselves (0.90), suggests that they are effectively placed on an equal footing.

Concluding remarks

Overall, the analysis herein confirms that the GII framework is statistically sound. In fact, the vast majority of indicators (71 out of the 78) are found to be sufficiently influential -in a statistical sense- in the GII framework. This result signals the efforts over the past eighteen years that the GII team has put into the preparation of this monitoring framework to identify the multiple determinants of a county’s innovation capacity and potential and the best available data sources to measure them.

The following issues are worth of further consideration.

For two of the 78 indicators (5.3.4 FDI net inflows and 6.2.1 Labor productivity growth) the statistical fit with the Index was found to be weak – that is, each of these two indicators explains less than 9 percent of economies’ variation in their respective sub-pillar scores.

In addition, special attention should be given to indicator 5.1.3 Youth Demographic Dividend, given the negative correlation fit with other indicators within the index. The Youth Demographic Dividend indicator notably favors African countries by capturing their unique demographic advantage and future innovation potential driven by youthful populations. While this forward-looking measure is conceptually important, its strong negative correlations may undermine the framework’s ability to reliably differentiate and rank countries. Therefore, the JRC-COIN recommends including it as a valuable contextual element rather than as a core part of the monitoring framework in future index editions.

Added value of the GII

High statistical association between the components of a composite index could be interpreted by some as a sign of redundancy of information within the composite index. For the case of the GII, the Input and Output Sub-Indices correlate strongly with each other and with the overall GII, while the five pillars in the Input Sub-Index have a very high statistical reliability. However, the tests conducted by the JRC-COIN confirm that this high statistical reliability does not result in redundancy of information. In particular, a country's GII ranking differs from that in any of the seven pillars by 10 positions or more at least 47 percent (up to 76 percent) of the 139 economies included in the GII 2025 (Appendix Table 3). This serves as a demonstration of the added value of the GII ranking, which helps to highlight other aspects of innovation within individual countries that are not immediately apparent from analysis of the seven pillars individually. It also highlights the usefulness of taking due account of the information contained in each of the GII pillars, sub-pillars and indicators individually. By doing so, economy-specific strengths and bottlenecks in terms of innovation can be identified and serve as a basis for evidence-based policymaking.

Step 4: Qualitative review

Lastly, JRC-COIN evaluated the GII results – in particular, the overall economy classifications and relative performances in terms of the Innovation Input or Output Sub-Indices – with the aim to verify that the overall results are robust with respect to the modeling assumptions made during the construction of the GII. Robustness is a powerful characteristic for a composite index as it verifies its reliability as a monitoring framework of the underlying phenomenon that is being measured. Overall, the results in this section verify the robustness of GII with respect to modeling assumptions and its reliability as a monitoring framework for innovation performance. Notwithstanding these positive results, the structure of the GII model is, and has to remain, open to future improvements which may be needed as better data, more comprehensive surveys and assessments, and new, relevant research studies become available.

The impact of modeling assumptions on the GII results

An important part of the GII statistical audit is to check the effect of varying assumptions within plausible ranges. Modeling assumptions with a direct impact on GII scores and rankings relate to:

the underlying structure selected for the index based on pillars;

the choice of individual variables to be used as indicators;

decisions regarding whether (and how) to impute missing data;

decisions regarding whether (and how) to treat outliers;

the selection of the normalization formula to be used;

the choice of aggregation weights for indicators and their aggregates; and

the aggregation rule to be used at each different level of the index structure.

The rationale for the choices made by the GII developers regarding each of these issues is well-grounded: for instance, expert opinion coupled with statistical analysis informs the selection of the individual indicators; common practice and easier interpretation suggest the use of a minimum–maximum normalization approach in the [0–100] range; statistical analysis guides the treatment of outliers; while simplicity and parsimony criteria advocate for the developers' choice for not imputing missing data. The uncertainty that naturally stems from the above-mentioned modeling choices is accounted for in the robustness assessment carried out by the JRC-COIN. In particular, the methodology applied allows for the joint and simultaneous analysis of the impact of such choices on the aggregate scores. The analysis carried out by JRC-COIN supplements the GII 2025 individual economy rankings with confidence intervals, to better appreciate the robustness of these ranks to the modeling choices.

As suggested by the relevant literature on composite indicators

The Monte Carlo simulation comprised 5,000 runs of different sets of weights for the seven GII pillars. Weights were assigned to the pillars based on random perturbations centered on the reference values. The ranges of simulated weights were defined by considering both the need for a wide enough interval to allow for meaningful robustness checks and the need to respect the underlying principle of the GII that the Input and the Output Sub-Indices should be placed on an equal footing. As a result of these considerations, the limit values of uncertainty for the five input pillars are between 10 and 30 percent, whereas the limit values for the two output pillars are between 40 and 60 percent (Appendix Table 4).

The rationale for the choices made by the GII developers regarding each of these issues is well-grounded: for instance, expert opinion coupled with statistical analysis informs the selection of the individual indicators; common practice and easier interpretation suggest the use of a minimum–maximum normalization approach in the [0–100] range; statistical analysis guides the treatment of outliers; while simplicity and parsimony criteria advocate for the developers' choice for not imputing missing data. The uncertainty that naturally stems from the above-mentioned modeling choices is accounted for in the robustness assessment carried out by the JRC-COIN. In particular, the methodology applied allows for the joint and simultaneous analysis of the impact of such choices on the aggregate scores. The analysis carried out by JRC-COIN supplements the GII 2025 individual economy rankings with confidence intervals, to better appreciate the robustness of these ranks to the modeling choices.

The rationale for the choices made by the GII developers regarding each of these issues is well-grounded: for instance, expert opinion coupled with statistical analysis informs the selection of the individual indicators; common practice and easier interpretation suggest the use of a minimum–maximum normalization approach in the [0–100] range; statistical analysis guides the treatment of outliers; while simplicity and parsimony criteria advocate for the developers' choice for not imputing missing data. The uncertainty that naturally stems from the above-mentioned modeling choices is accounted for in the robustness assessment carried out by the JRC-COIN. In particular, the methodology applied allows for the joint and simultaneous analysis of the impact of such choices on the aggregate scores. The analysis carried out by JRC-COIN supplements the GII 2025 individual economy rankings with confidence intervals, to better appreciate the robustness of these ranks to the modeling choices.

As suggested by the relevant literature on composite indicators

The Monte Carlo simulation comprised 5,000 runs of different sets of weights for the seven GII pillars. Weights were assigned to the pillars based on random perturbations centered on the reference values. The ranges of simulated weights were defined by considering both the need for a wide enough interval to allow for meaningful robustness checks and the need to respect the underlying principle of the GII that the Input and the Output Sub-Indices should be placed on an equal footing. As a result of these considerations, the limit values of uncertainty for the five input pillars are between 10 and 30 percent, whereas the limit values for the two output pillars are between 40 and 60 percent (Appendix Table 4).

For transparency and replicability purposes, the GII team has always opted not to estimate missing data. In the cases where missing data exist, the score of the aggregate containing the missing value is based on the other elements of the aggregate for which values are observed. This "no imputation" choice is common in similar contexts and is usually selected to improve transparency and avoid any methodological black box in the imputation of data. Technically, this constitutes a form of "shadow" imputation (for example, in an arithmetic average it is equivalent to replacing the missing value with the arithmetic average of the elements for which values are observed). Hence, the available data (indicators) in the incomplete pillar may dominate, sometimes biasing the ranks up or down. To test the impact of not imputing missing values, the JRC-COIN estimated missing data using two different data imputation approaches: (a) the expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm and (b) the nearest neighbor (k-NN) approach (using the 10 nearest neighbors). Both these were applied within each GII pillar and then compared to the no-imputation approach (see Appendix Table 6).

Regarding the aggregation formula, decision-theory practitioners challenge the use of simple arithmetic averages because of their fully compensatory nature, where a country's high comparative advantage on a few indicators can compensate for its comparative disadvantage on many other indicators (

Six models were tested based on the combination of no imputation versus EM or k-NN imputation and arithmetic versus geometric average, with the geometric average being the variation of the generalized mean that allows the least compensability among those tested. A random combination of these choices plus a random set of perturbed weights were used in a total of 5,000 simulations for the GII and each of the two sub-indices (see Appendix Table 4 for a summary of the uncertainties considered).

Uncertainty analysis results

The main results of the robustness analysis are shown in Appendix Figure 1, with median ranks and 90 percent confidence intervals computed across the 5,000 Monte Carlo simulations for the GII and the two sub-indices. Economies are in ascending order (best to worst performing) according to their reference rank (black line), with the dot representing the median rank over the simulations.

Appendix Figure 1 Robustness analysis of the GII, Input and Output Sub-Indices

All published GII 2025 ranks lie within the simulated 90 percent confidence intervals and for most economies these intervals are sufficiently narrow to allow meaningful inferences to be drawn: For 85 of the 139 economies the width of the 90% GII rank confidence interval is less than 10 positions in rank, while this holds for 103 of the 139 economies in the case of the Input Sub-Index and for 107 in the case of the Output Sub-Index. However, it is also true that a few economies experience significant changes in rank with variations in weights and aggregation formula and when imputing missing data. Seven economies – Bahrain, Seychelles, Botswana, Brunei Darussalam, Ghana, Madagascar and Malawi – have 90 percent confidence interval widths of more than 20 positions (21, 29, 24, 33, 21, 26 and 23 positions, respectively). Consequently, their rankings (62nd, 75th, 87th, 88th, 101th, 120th and 125th) in the GII classification should be interpreted cautiously and not taken at face value. However, this is a remarkable improvement compared to GII versions up to 2016, when more than 40 economies had confidence interval widths of more than 20 positions. The improvement in the confidence that can be placed in the GII 2025 ranking is the direct result of the decision to adopt a more stringent criterion for an economy's inclusion since 2016, which now requires at least 66 percent data availability within each of the two sub-indices.

In a similar fashion, some caution is also warranted with regards to the ranking of three economies (Cabo Verde, Bolivia and Belarus) for the Input Sub-Index, for which the 90 percent confidence interval has a width of more than 20 positions (21, 25 and 21 respectively). A similar degree of caution is needed in the Output Sub-Index for four economies – Seychelles, Ghana, Côte d'Ivoire and Malawi – which have 90 percent confidence interval widths of more than 20 positions (up to 40 for Seychelles). The higher data availability in the Output Sub-Index in the latest GII editions has contributed to reducing the number of countries with very wide intervals compared to previous editions (e.g., the GII 2019 edition in which there were 13 countries with confidence intervals wider than 20 positions).

Although the rankings for a few economies in the GII or in the two sub-indices appear to be sensitive to methodological choices, the published rankings for the vast majority of the 139 countries included in the 2025 GII can be considered as representative of the plurality of scenarios simulated in this audit. Taking the median rank as the benchmark for an economy's expected rank in the realm of the GII's unavoidable methodological uncertainties, 73 percent of the economies are found to shift fewer than three positions with respect to the median rank in the GII; the percentage for the Input and the Output Sub-Indices is similarly large (at 64 and 59 percent respectively).

In order to offer full transparency and complete information, Appendix Table 5 reports the GII 2025 Index and Input and Output Sub-Indices' economy ranks together with the simulated 90 percent confidence intervals to allow a better appreciation of the robustness of the results to the choice of weights and aggregation formula and the impact of estimating missing data (where applicable).

Sensitivity analysis results

Complementary to the uncertainty analysis, sensitivity analysis has been used to identify which of the modeling assumptions have the greatest impact on certain country rankings. Appendix Table 6 summarizes the impact of changes in the imputation method (EM or k-NN imputation) and/or the aggregation formula (geometric aggregation), keeping the aggregation weights fixed at their reference values (as in the nominal GII). Similar to the results of previous audits, neither the GII nor the Input or Output Sub-Indices are found to be heavily influenced by the imputation of missing data, or by the aggregation formula. Regarding the GII index, there is only one economy (Botswana) that shifts rank by more than 20 positions when a combination of a different aggregation and imputation method is used (EM or k-NN). A similar case can be observed for Ghana and the Output Sub-Index. The choice of the imputation method appears to also be crucial for the ranking of two other countries in the case of the Output Sub-Index, namely Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire. For these countries, missing data account for 16 and 8 percent of the Output Sub-Index indicators.

Overall, the analysis carried out by JRC-COIN verifies that the rankings of the 2025 GII are reliable and, for most economies, the simulated 90 percent confidence intervals are narrow enough to allow meaningful inferences to be drawn for their relative performance. There are a few economies that appear to be sensitive to the way missing values are treated, most of which have a rather large share of missing data. It is however suggested that the readers of the GII 2025 report consider an economy's ranking in the GII 2025 and in the Input and Output Sub-Indices not only at face value, but also within the 90 percent confidence intervals, in order to better appreciate the degree to which an economy's rank depends on modeling choices.

These confidence intervals also have to be taken into account when comparing economy rank changes from one year to the next at the GII or Innovation sub-index level in order to avoid drawing erroneous conclusions about an economy's rise or fall in the overall classifications. Since 2016, following the JRC-COIN recommendation in past GII audits, the developers' decision to apply the 66 percent indicator coverage threshold separately to the Input and Output Sub-Indices in the GII has led to a net increase in the reliability of economy rankings for both the GII and the two sub-indices. Furthermore, the adoption in 2017 of less stringent criteria for skewness and kurtosis (greater than 2.25 in absolute value and greater than 3.5, respectively) has not introduced any bias into the estimates.

Best-practice frontier in the GII by data envelopment analysis

Can economies' multifaceted innovation performance be benchmarked fairly without applying a fixed and uniform set of weights that might be unfair to a particular economy?

Innovation policies at the national level must strike a balance between global trends and each country's unique context, strategies, and challenges. Evaluating multidimensional innovation performance by applying a common set of weights to all economies could hinder the acceptance of an innovation index, as the chosen weighting scheme might be perceived as unfair to specific economies, as it does not reflect their national priorities or the distinct challenges they encounter compared to others. A notable advantage of data envelopment analysis (DEA), as applied in real world decision-making contexts, is its determination of endogenous weights that optimize each decision-making unit's overall score, given a set of other observations. In the absence of a global consensus or strategy on innovation activity priorities, and with numerous national innovation strategies influenced by diverse country-specific factors, this approach presents a reasonable alternative to using uniform weights across economies.

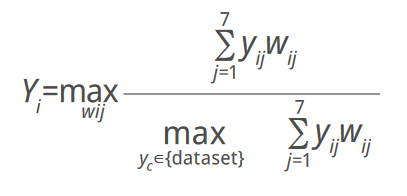

In this section we relax the assumption of fixed pillar weights common to all economies by allowing economy-specific weights that maximize an economy's global innovation score to be determined endogenously by means of the Benefit-of-the-Doubt (BoD) model, a tailored DEA model that is suitable for the case of composite indicators construction.

A key question that arises from the GII approach is the following: Can we compare economies' innovation performance across multiple dimensions without applying a fixed set of weights that might be unfair to some? The original question posed by the DEA literature was how to measure each unit's relative efficiency in production compared to a sample of peers, given observations on input and output quantities and, often, no reliable information on prices

(bounding constraint), subject to wij ≥ 0, where, j = 1,...,7, i = 1,...,139 (non-negativity constraint). In this linear programming problem, the weights are non-negative and an economy's score is between 0 (worst) and 1 (best). The programming problem used to calculate the DEA-BoD socres in this audit included also the restrictions: 0.2 ≥ (wij*yij)/Σ(wij*yij) ≥ 0.05, j = 1,...,7 (contribution restrictions).

In theory, each economy is free to decide on the relative weight of each innovation pillar, such as to achieve the best possible score, allowing for a better reflection of its unique innovation strategy. In practice, the DEA-BoD method assigns a higher (lower) weight to those pillars in which an economy is relatively strong (weak). Reasonable constraints are applied to the weights to preclude the possibility of an economy achieving a perfect score by assigning a zero weight to weak pillars: for each economy, no pillar can contribute less than 5% or more than 20% to an economy's total score. The DEA-BoD score is then calculated as a weighted average of the seven innovation pillar scores, using the economy-specific weights determined by the DEA-BoD method. This score is compared to the best performance among all other economies using the same weights. The DEA-BoD score can be interpreted as a measure of the "distance to the best-practice frontier."

Appendix Table 7 presents pie shares and DEA scores for the top 25 economies in the GII 2025 alongside their respective GII 2025 rankings. All pie shares are in accordance with the starting point of granting leeway to each economy when assigning shares, while not violating the (relative) upper and lower bounds. In this year, Switzerland is the only economy to obtain a perfect DEA-BoD score of 1.00 – Sweden's score is 0.997 – indicating that it defines the best-practice frontier (in the 2024 GII, Sweden and Singapore were frontier economies as well). Sweden, Singapore, the United States (0.99), the Republic of Korea (0.97) and Finland (0.95) follow in terms of relative performance. The scores of these countries indicate that they are very close to the best-practice frontier: a proportional improvement of their pillar scores by 1%, 3% or 5% would make them frontier economies as well.

The seven pillars contribute differently to the performance scores of the top 25 economies, mirroring the varied priorities in their national innovation strategies. These differences also highlight each economy's strengths in specific GII pillars compared to others, revealing their comparative advantages. For instance, Ireland and Australia obtain the same performance score (0.87) but Australia relies less on the Output pillars to do so (each of them is allocated a 5% of the DEA score), while Ireland allocates 20% of its score to the Business sophistication pillar and 10% to the Knowledge and technology outputs pillar. In a similar fashion, Denmark and the United Kingdom receive roughly the same score (0.93 and 0.92 respectively), but their pillars contribute differently to it: both countries allocate 20% – the maximum possible – of their score to Human capital and research and Business sophistication, in which both are very well-performing. However, the United Kingdom allocates another 20% on the Knowledge and technology outputs pillar (versus 5% for Ireland), and less than Ireland on the Institutions and Infrastructure Input pillars (5% and 10% respectively, while Ireland allocates 20% on both. Appendix Figure 2 shows how close the DEA-BoD scores and the GII 2025 scores are for all the 139 economies (Pearson correlation of 0.995).

Conclusion

The JRC-COIN analysis affirms that the multilevel structure of the GII 2025, encompassing 78 indicators, 21 sub-pillars, seven pillars, and two sub-indices, is statistically robust and well-balanced. Each sub-pillar contributes similarly to the variation within its respective pillar, ensuring a coherent and reliable framework. The continuous refinements by the development team have strengthened the GII's statistical integrity, with most indicators effectively distinguishing between economies' performances at the sub-pillar level or lower.

The decision not to impute missing values, which is common in comparable contexts and justified on the grounds of transparency and replicability, can at times have an undesirable impact on some economies' scores, with the additional negative side-effect that it might encourage economies not to report low data values. The GII team's adoption, in 2016, of a more stringent data coverage threshold (at least 66 percent data availability for each of the input- and output-related indicators) has notably improved confidence in the economy ranking for the GII and the two sub-indices. In addition, the notable increase of included countries by six (compared to previous GII editions) highlights the fruitfulness of encouraging continuous data collection and monitoring by the developers. The results of the analysis carried out by JRC-CC-COIN suggest that the developer's decision not to impute missing values has a notable impact in the rankings of only a very small set of countries and only for the case of the Input or the Output Sub-Indices. Notably, only four or five countries exhibit a change in their rank by more than 20 positions when alternative imputation methods are used in the GII 2025.

Additionally, the GII team's decision, in 2012, to use weights as scaling coefficients during index development constitutes a significant departure from the traditional, yet erroneous, vision of weights as a reflection of indicators' importance in a weighted average. It is hoped that such an approach will be adopted by other developers of composite indicators to avoid situations where bias sneaks in when least expected.

The JRC-COIN analysis also confirmed that the strong correlations between GII components do not lead to information redundancy. For a significant portion of the 139 economies in the GII 2025 (more than 47% and up to 76%), the GII ranking and the rankings of individual pillars differ by 10 positions or more. This demonstrates the added value of the GII in highlighting diverse aspects of innovation and the importance of examining both the overall ranking and individual pillars, sub-pillars, and indicators to identify economy-specific strengths and bottlenecks.

All published GII 2025 rankings lie within the simulated 90 percent confidence intervals that take into consideration the unavoidable uncertainties inherent in an estimation of missing data, the weights (fixed vs. simulated) and the aggregation formula allowing various levels of compensability between the arithmetic and the geometric average at the pillar level. For the majority of economies, such intervals are narrow enough for meaningful inferences to be drawn: the intervals comprise 10 or fewer positions for 90 out of the 139 considered economies. The GII rankings of five economies– Qatar, Madagascar, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Barbados and Brunei Darussalam – should however be interpreted with some caution, as they appear to be highly sensitive to the methodological choices. The Input and Output Sub-Indices have the same modest degree of sensitivity to the methodological choices relating to the imputation method, weights or aggregation formula. Economy ranks, either in the GII 2025 or in the two sub-indices, can be considered to be representative of the many possible scenarios: 81 percent of the economies shift fewer than three positions with respect to the median rank within the GII, 78 percent within the Input Sub-Index and 76 percent within the Output Sub-Index.

All things considered, the JRC-COIN audit findings confirm that the GII 2025 meets international quality standards for statistical soundness, indicating that it is a reliable benchmarking tool for innovation practices globally. The GII is a well-maintained highway towards better policymaking in the field of innovation.

The "distance to the best-practice frontier" measure, derived from data envelopment analysis, offers a suitable alternative approach to benchmarking innovation performance without imposing a fixed and common set of weights to the benchmarked countries. The recalculated DEA-based GII is very closely correlated with the nominal GII rankings, and at the same time it allows economies to highlight their relative strengths and potential national priorities more effectively.

The GII should be viewed as an ongoing effort to capture the complexity of innovation, continuously adapting to improvements in data availability and theoretical advances. It represents a transparent and mature attempt to inform and improve innovation policies worldwide over its 18-year history of refinement. The GII should not be viewed as the ultimate and definitive ranking of economies but rather a dynamic framework that evolves to better reflect the richness of innovation. This ongoing process ensures that policymakers have access to the most accurate and actionable information to drive evidence-based innovation strategies.

References

Becker, W., M. Saisana, P. Paruolo and I. Vandecasteele (2017). Weights and importance in composite indicators: Closing the gap. Ecological Indicators, 80, 12–22.

Charnes, A. and W.W. Cooper (1985). Preface to topics in data envelopment analysis. Annals of Operations Research, 2, 59–94.

Cherchye, L., W. Moesen, N. Rogge, T. Van Puyenbroeck, M. Saisana, M. et al. (2008). Creating composite indicators with DEA and robustness analysis: The case of the Technology Achievement Index. Journal of Operational Research Society, 59(2), 239–251.

Cook, W.D., K. Tone and J. Zhu (2014). Data envelopment analysis: Prior to choosing a model. Omega, 44, 1–4.

European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (2024). European Innovation Scoreboard. Publications Office of the European Union, available at:https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/779689.

Groeneveld, R.A. and G. Meeden (1984). Measuring skewness and kurtosis. The Statistician, 33(4), 391–399.

Little, R.J.A. and D.B. Rubin (2002). Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 2nd edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Melyn, W. and W. Moesen (1991). Towards a Synthetic Indicator of Macroeconomic Performance: Unequal Weighting When Limited Information Is Available. Public Economics Research Paper 17. Leuven: Centre for Economic Studies.

Montalto, V., C.J. Tacao Moura, S. Langedijk and M. Saisana (2019). Culture counts: An empirical approach to measure the cultural and creative vitality of European cities. Cities, 89, 167–185.

Munda, G. (2008). Social Multi-Criteria Evaluation for a Sustainable Economy. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Nunally, J. (1978). Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

OECD/EC JRC (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development/European Commission, Joint Research Centre). (2008). Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. Paris: OECD.

Paruolo, P., M. Saisana and A. Saltelli (2013). Ratings and rankings: Voodoo or science? Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, A 176(3), 609–634.

Saisana, M., A. Saltelli and S. Tarantola (2005). Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis techniques as tools for the analysis and validation of composite indicators. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, A 168(2), 307–323.

Saisana, M., B. D'Hombres and A. Saltelli (2011). Rickety numbers: Volatility of university rankings and policy implications. Research Policy, 40(1), 165–177.

Schneider, T. (2001). Analysis of incomplete climate data: Estimation of mean values and covariance matrices and imputation of missing values. Journal of Climate, 14(5), 853–871.

Vertesy, D. (2016). A Critical Assessment of Quality and Validity of Composite Indicators of Innovation. Paper presented at the OECD Blue Sky III Forum on Science and Innovation Indicators. Ghent, 19–21 September 2016.

Vertesy, D. and R. Deiss (2016). The Innovation Output Indicator 2016: Methodology Update, EUR 27880. Luxembourg: European Commission, Joint Research Centre.

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) (2023). Global Innovation Index 2023: Innovation in the Face of Uncertainty. Geneva: WIPO. DOI:10.34667/tind.48220.

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) (2024). Global Innovation Index 2024: Unlocking the Promise of Social Entrepreneurship. Geneva: WIPO. DOI:10.34667/tind.50062.