In the music industry today, fandom is everything. “Superfan” is the latest buzzword, as artists and labels realize that loyal fans can be more valuable than hit songs.

In the Republic of Korea, this is old news. Through livestreams, reality shows and exclusive fan events, K‑pop companies have long nurtured a culture designed to convert casual listeners into dedicated followers and strengthen the bond between fans and idols (the name given to K-pop entertainers, whether solo artists or band members).

Labels sustain this culture with the help of intellectual property (IP) strategies that go beyond music copyright, trademarked logos and merchandise designs, while the K‑pop industry at large is attentive to the IP that protects fandom assets.

Then there are the fans themselves. Through their understanding of IP issues such as copyright and trademark ownership, K‑pop devotees are better able to learn about their idols’ upcoming releases and celebrate their achievements. Fans even go so far as to defend their idols’ IP rights when they detect a violation.

Passionate fan support often translates into a desire to protect idols

K‑pop acts are typically launched following careful planning and investment from multinational conglomerates such as SM Entertainment, Hybe Corporation, JYP Entertainment and YG Entertainment, the market’s leading players. These companies operate as record labels, talent agencies, music production companies, event management and concert production companies, and publishing houses.

Labels hold auditions and select talent to form new groups according to their creative and commercial aims, before training their artists to ready them for the studio and the stage. They are outspoken and deliberate about their use of IP throughout.

Hybe IPX and JYP Three Sixty, subsidiaries of Hybe and JYP Entertainment, respectively, have branches dedicated to IP licensing. Some companies include chapters on IP in their investor briefings, as in SM Entertainment’s SM 3.0: IP Monetization Strategy. Hybe releases public statements about its IP policies and the actions it takes against those who infringe upon its IP rights and those of its artists.

K‑pop companies also issue fan etiquette notices, which include rules on IP awareness and encourage fans to help them identify violations. In 2023, SM Entertainment launched KWANGYA 119, a service through which fans can report IP infringements. According to one of the company’s lawyers, the service receives an average of 400 reports per month.

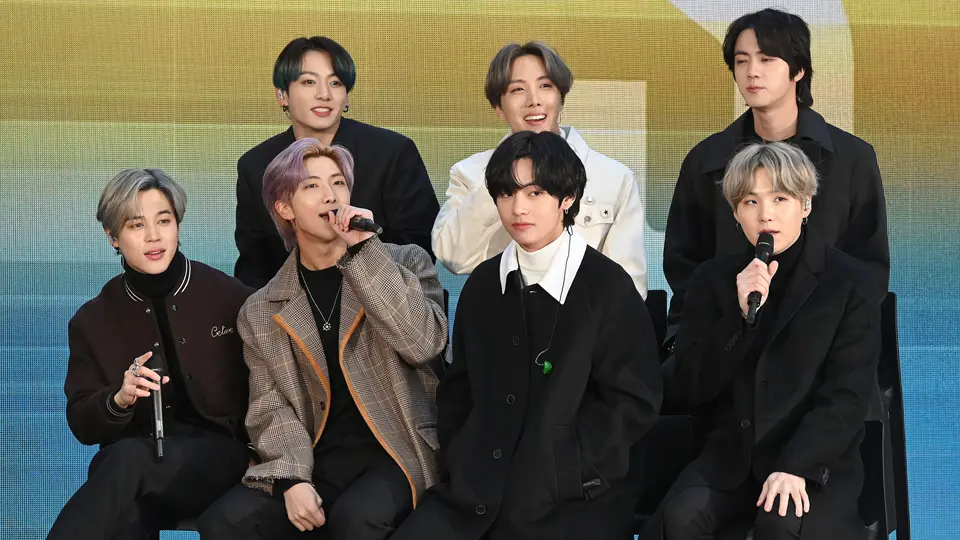

BTS Army vs Lalalees in Borahae trademark dispute

Fans often notify the owner of the IP while calling out the violator. In 2021, the BTS Army, the official fanbase of boy band BTS, found that cosmetics company Lalalees had filed a trademark application for the expression “I purple you” (Korean: “보라해”, or “borahae”). The word “borahae” turns “purple” into a verb meaning “to love” and is part of the BTS fan vernacular. When fans discovered that Lalalees was trying to capitalize on the term, they flooded its social media pages with comments and reported the issue to Hybe, BTS’s management company. Lalalees withdrew its application and issued an apology to the fandom.

The borahae incident exemplifies a broader pattern in K‑pop culture. Passionate fan support often translates into a desire to protect idols, making IP infringement a frequent topic of debate. Such discussions can involve claims of groups or companies “copying” each other’s concepts, sampling disputes or even allegations of music plagiarism.

K‑pop song copyright: beyond the music

As across the entire music industry, copyright protects the core product of K‑pop: songs and albums. Korea’s music business is one of the most successful globally. In 2023, the Korean Music Copyright Association (KOMCA) was ranked the world’s ninth biggest collector of music royalties, collecting around €279 million.

According to annual stats released by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), K‑pop was the leading global genre in physical and digital music sales in 2024. On the IFPI Global Album Sales Chart 2024, 17 of the top 20 albums belonged to K‑pop.

Fan accusations of likenesses between songs, music videos and aesthetics led to controversies

Music aside, copyright also protects other assets essential to K‑pop fandom. The fan-idol relationship is fostered on specific platforms and apps, such as Hybe's Weverse and SM's LYSN (which includes the Bubble app) that utilize copyright-protected software and company content. Building on conventional social media platforms, these networks offer a distinct way for idols to interact with fans and for fans to feel intimately connected, also within the fandom.

Another integral part of K‑pop is dancing, making choreographies a relevant and occasionally disputed topic. Notable cases involve the choreography of Secret’s 2011 song “Shy Boy”, which was recognized as a copyrighted work by the Seoul District Court the year of the song’s release.

More recently, in 2024, a controversy over an alleged choreographic resemblance between two girl groups sparked debate about dance copyrights in Korea. NewJeans’ producer Min Hee-jin claimed that the dance routine to Illit’s “Lucky Girl Syndrome” copied several of NewJeans’ choreographies. Many NewJeans fans supported the charge and pointed out similarities in other Illit dance moves as well.Fan accusations of likenesses between the songs, music videos and aesthetics of groups such as NewJeans, Illit and Le Sserafim also led to controversies between the groups’ labels, which then released public statements and took legal actions against the spread of defamation and false information.

Fan tracking of K‑pop songwriting credits

Given the commercialized and carefully controlled nature of K‑pop, idols haven’t always had a hand in writing and producing their music. However, the success of groups such as BigBang and BTS has seen idols uplifted to the status of songwriters and producers. Today, members of K‑pop bands such as Ive and Seventeen have songwriting credits on the groups’ albums. The same is true for all seven members of BTS and all nine members of Twice.

Even when the music is not written or produced by the groups who perform it, K‑pop fans are eager to know more about the people behind the hits. When an album tracklist is revealed, fans seek more information on the producers’ and writers’ previous song credits. Blogs such as The Bias List highlight the work of K‑pop songwriters and producers, and fans advocate crediting artists and copyright holders when sharing art, pictures and videos.

K-pop enthusiasts also use official IP databases to figure out where credit is due. When an idol becomes a full member of KOMCA (requirements include receiving a certain amount of royalties from their copyrighted songs per year), the news is usually the subject of celebratory hashtags and other supporting projects. Moreover, monitoring song registrations on the KOMCA online database allows fans to find out about new music from their idols.

K‑pop brands: trademarks of band names

K‑pop fans also scan other IP databases to stay informed and uncover new information. They often turn to the KIPRIS (Korea Intellectual Property Information Search) online database to search for trademark applications filed by K‑pop companies.

In their essay on fandom trademarks, Ana Clara Ribeiro and Paula Giacomazzi Camargo found that trademarks are one of many assets involved in artists’ careers and their relationships with their fanbase.

In their most basic form, trademarks protect K‑pop groups’ names and logos. Some companies trademark the group name as a romanized word mark and also in hangeul, the Korean alphabet. For example, girl group Aespa’s name is trademarked both in romanized and hangeul (에스파), and in a stylized font.

Trademarking fandom names

But trademarking a group’s name is just the start. K‑pop companies also register other names, such as those of fandoms. K‑pop labels typically create fandoms in tandem with their groups’ brands. Army (BTS), ReVeluv (Red Velvet) and NCTzen (NCT) are all fandom names trademarked under the Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO). Even event names – such as SM Entertainment’s S.M. ART Exhibition – are registered.

The protection also extends to groups’ nicknames – such as SuJu and Tubatu, used to refer to Super Junior and TXT, respectively – and to the stage names of K‑pop idols such as BoA, NingNing and G-Dragon, as well as song titles.

Trademark ownership disputes in K-pop

Because K‑pop groups are the outcome of strategic planning and investment by conglomerates, it's the conglomerates that own the trademarks. However, this may be changing. In 2022, GOT7 reached an agreement with JYP Entertainment to transfer the trademark from the company to the band’s members. The accord set a precedent, followed in 2025 by former YG Entertainment artist G-Dragon.

Not all artists have been so lucky. After a setback in its case against record label Ador in March 2025, NewJeans announced their hiatus. The ruling forbade the group – who wanted to rebrand as NJZ – from organizing their own appearances, making music or signing advertising deals during their dispute.

K-pop lightsticks and merchandise

While much fan culture now lives online, concerts and in-person experiences make up a massive part of K‑pop. One of the most characteristic products of fan culture that combines design registrations and patents is the lightstick, a handheld device designed to allude to a K‑pop group’s name and aesthetics.

The devices synchronize with live or recorded music via Bluetooth – technology that can be the subject of complex patents. SM Entertainment owns numerous design applications and registrations related to its groups’ lightsticks, while Hybe owns designs and patents for its own.

Fans’ relationship with their lightsticks goes beyond the purchase as merchandise – they’re symbols of fandom identity that foster a sense of unity during live performances. It is common for K‑pop fans to bring their lightsticks even to events that are not related to K‑pop.

As with copyright and trademarks, fans search the KIPO database to find design registrations and patent applications filed by K‑pop companies. That’s how the BTS ARMY discovered the upcoming release of a personalized 3D slide viewer in 2021. The discovery created buzz on social media and Weverse, where the product quickly sold out.

Clearly, K‑pop fans are more than passive consumers – they are active participants in the K‑pop ecosystem. And IP plays a significant role in shaping this dynamic. Harnessing fan action as part of their IP strategies while also using IP for commercial aims, K‑pop companies turn enthusiasts into advocates with an acute awareness of how crucial IP is to the industry. From music and audiovisual content to choreography, performances and merchandise, K-pop is a powerful medley built around intellectual property, carefully guarded by companies and fans alike.

About the author

Ana Clara Ribeiro is an attorney, writer, judicial expert and researcher. She practices at Baril Advogados in Brazil, focusing on trademarks, copyright and strategies for the media and entertainment industries. She is currently a Master’s student in Intellectual Property and Innovation at Brazil’s National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI). Ms Ribeiro is also an international music writer with bylines in Rolling Stone, PopMatters, Remezcla, Consequence and many other websites, with K‑pop being one of her specialties.